Asclepius and Jesus—The Resurrection That Wasn’t

Jesus and Asclepius both healed the sick—but one ended up a god in the stars, and the other ended up on a Roman cross. Here’s why their “resurrections” are nothing alike—and why Jesus wasn’t copied from a Greek myth.

Just because two characters heal people doesn’t mean they’re literary twins. The Greek god Asclepius and Jesus both had divine parentage and were associated with healing—but one was a mythological doctor-turned-constellation, and the other was a first-century Jewish preacher whose followers claimed he rose from the dead. Spoiler: nobody confused the two in antiquity.

Who Was Asclepius, and Why Are We Talking About Him?

Asclepius was the son of Apollo and a mortal woman named Coronis. He began as a mortal physician, showed off some next-level healing skills, and gradually earned divine status in the Greek world. His cult became wildly popular, especially among those hoping for a miraculous cure without having to see a dentist.

People would travel to healing temples called Asclepieia, where they’d sleep in sacred spaces hoping for a dream-prescription from the god himself. These weren’t just glorified clinics—they were religious centers where dreams and serpents held diagnostic authority.

Parallelism: Because Apparently Everything Is a Copy

Was the Adulterous Woman in the Original John?

From Sheol to Hell: Afterlife Beliefs Evolved

Jesus vs Krishna: Not the Same Story

The Resurrection... Sort Of?

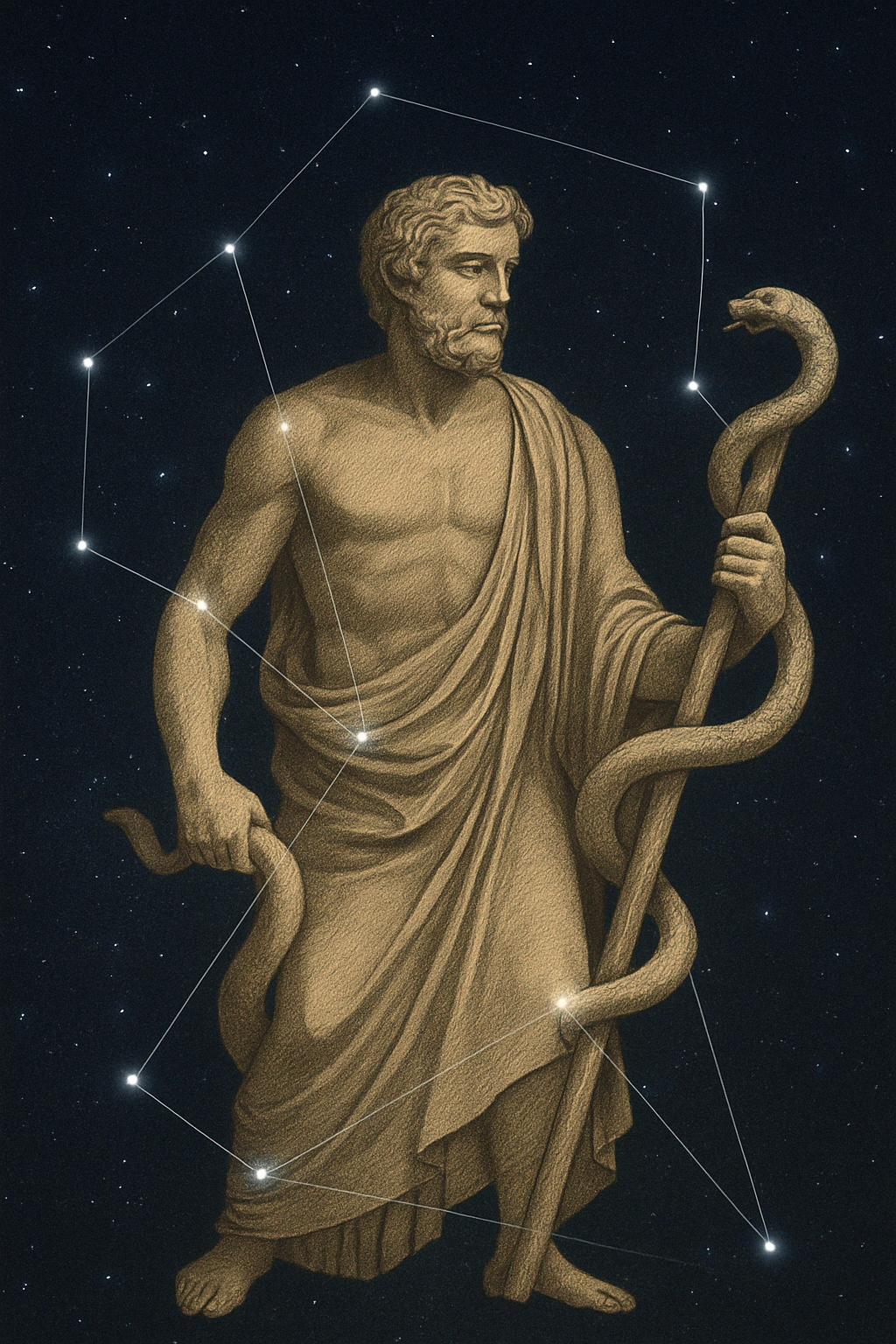

In some versions of the myth, Asclepius became so good at healing that he started raising the dead. Zeus, not a fan of moral overachievement (or perhaps just maintaining the cosmic order), responded by frying him with a thunderbolt (Apollodorus, Library 3.10.3). In other versions, such as in the works of Pindar (Pythian Odes 3.54–58) and Diodorus Siculus (Library of History 4.71.1–3), Asclepius is later honored or resurrected in a divine sense—either by being restored to life and elevated to Olympus or placed in the sky as the constellation Ophiuchus.

So which is it? That depends on which poet or historian you ask. The myths contradict one another. What they do not describe is a bodily resurrection on Earth in which Asclepius reunites with his followers, eats meals, or appears in public settings post-mortem. He doesn’t rise from the grave to offer motivational speeches over breakfast. He gets deified—or memorialized—but the ancient sources are frustratingly inconsistent on the details.

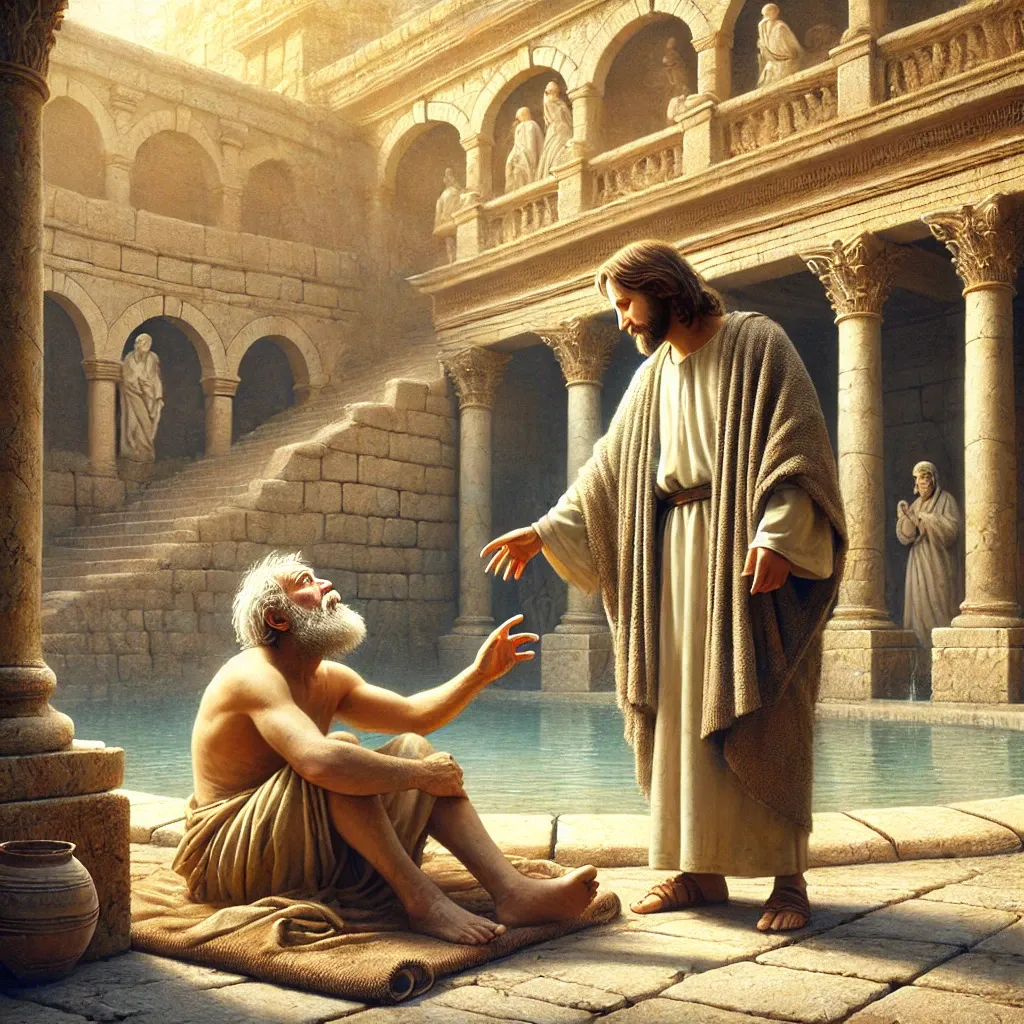

The Pool of Bethesda: Was It an Asclepian Spa Day?

Some argue the pool in John 5:1–9—a site where Jesus heals a man—was once linked to Asclepian healing rites. But archaeological digs at the Bethesda site show it was likely a Jewish ritual bath complex, part of Second Temple purification practices, not a Greco-Roman healing sanctuary. As Eric Meyers and James Strange note, “there is no archaeological or literary basis for identifying the Bethesda pool with an Asclepian cult site” (74).

More importantly, in the story, the man never even makes it into the water. Jesus heals him with a simple command: “Get up, take your mat, and walk” (John 5:8, NRSVue). The entire scene functions not as an endorsement of healing traditions but as a dramatic contrast. Jesus bypasses the pool altogether, asserting his own authority over healing—without any dreams, serpents, or pagan pageantry.

Why These “Parallels” Fall Apart

Sure, both Asclepius and Jesus:

- Healed people

- Had divine backstories

- Were honored after death

- Got tangled up in resurrection rumors

But these are generic religious motifs—so broad that they apply to dozens of mythic and religious figures. Claims like “both were divine healers” or “both were venerated after death” are so vague that they’re essentially meaningless as evidence of literary or theological borrowing. It’s like saying Batman and Moses are the same because both wore capes and had origin stories involving trauma.

Internet memes and pop documentaries often highlight the most superficial similarities without doing the hard work of examining historical context, primary texts, or literary function. As Larry Hurtado puts it bluntly: “There is no evidence that the early Christian claims about Jesus were derived from or directly modeled on figures like Asclepius” (68).

The Crucial Differences

- Different Goals: Asclepius was about healing bodies. Jesus was about announcing the kingdom of God, offering spiritual renewal, and flipping religious expectations on their heads.

- Different Worlds: Asclepius lives in myth. Jesus walks into known history—under Roman rule, in specific locations, interacting with actual political figures.

- Different Resurrections: Asclepius’ “resurrection” is more like a divine promotion or celestial appointment. Jesus, according to the gospels, rises bodily, interacts with followers for weeks, and then ascends.

- Different Frameworks: Asclepius was never about sin, repentance, or salvation. His followers wanted pain relief, not eternal life. As Emma and Ludwig Edelstein explain: “Asclepius is a god of healing, not of salvation. His help is limited to physical disease, and he demands neither faith nor moral reformation” (615).

Conclusion: Jesus Wasn’t an Asclepius Reboot

No matter how hard you squint, Jesus doesn’t look like a retelling of Asclepius. The stories don’t match, the theology doesn’t align, and the historical setting isn’t remotely the same. What we have here is a case of surface-level similarities being blown out of proportion by those eager to find pagan roots in Christian soil.

Jesus wasn’t lifted from a Greek healing myth. And Asclepius? He never walked out of a tomb. He just got some nice temples, a cool staff with a snake, and maybe a thunderbolt to the face.

Works Cited

Apollodorus. The Library of Greek Mythology. Translated by Robin Hard, Oxford University Press, 1997.

Diodorus Siculus. Library of History. Translated by C.H. Oldfather, Harvard University Press, 1935.

Edelstein, Emma J., and Ludwig Edelstein. Asclepius: A Collection and Interpretation of the Testimonies. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1945.

Hurtado, Larry W. Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Eerdmans, 2003.

Meyers, Eric M., and James F. Strange. Archaeology, the Rabbis and Early Christianity: The Pool of Bethesda and the New Testament. Trinity Press, 1992.

Pindar. Pythian Odes. Translated by Diane Arnson Svarlien, Hackett Publishing, 1990.

Wright, N.T. The Resurrection of the Son of God. Fortress Press, 2003.

The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition (NRSVue). National Council of Churches, 2021.