The Attis Resurrection Myth: The Pagan Prototype That Wasn't

Internet skeptics claim the Gospels are just plagiarized Phrygian myths. But the ancient sources tell a different story—one of "glorified taxidermy" rather than resurrection. Here is why the Attis-Jesus parallel is a historical Mandela Effect.

If you spend enough time in the darker, less-literate corners of the internet, you’ll eventually run into the claim that Jesus is just a "copycat" of Attis—the Phrygian god of vegetation. The narrative is always the same: Attis was born of a virgin, died on a tree, and rose again three days later. It sounds like a slam dunk for the "Jesus is a myth" crowd. There is just one glaring problem: the ancient sources don’t actually say any of that.

What we are dealing with is a Historical Mandela Effect. Critics have spent so much time reading modern skeptical blogs that they’ve forgotten to check the actual primary texts. Before we dismantle the specific claims regarding Attis, it is important to understand that this is part of a larger, systemic effort to reduce the unique to the derivative.

RELATED READING: Whether it is the broader failure of parallelism, the debunked Jesus vs. Krishna comparisons, or the claim that Dionysus was the blueprint for Jesus, the tactic remains the same: ignore the context and invent a parallel. We even see this in holiday folklore, such as the persistent myth that the Easter Bunny is a pagan invention.

No Three-Day Resurrection in Sight

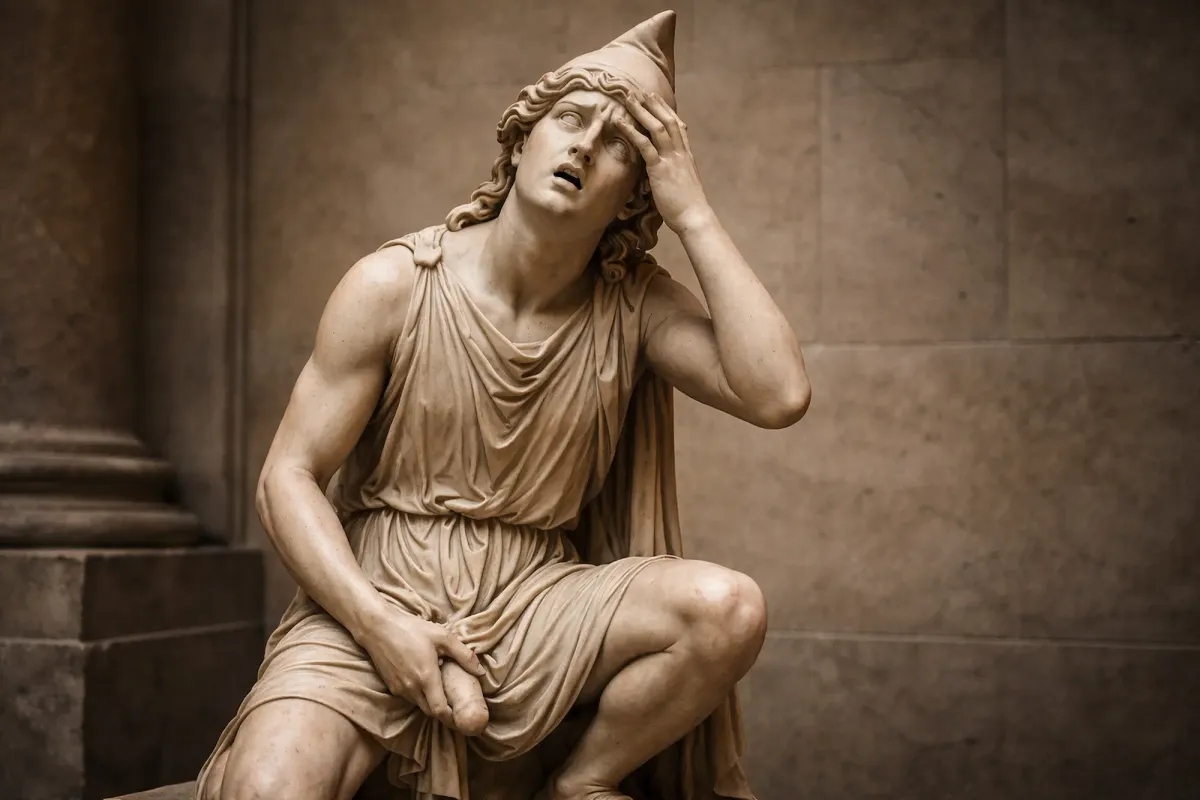

The most famous "parallel" is the three-day resurrection. Yet, when you look at the actual cult of Attis, the "resurrection" is nowhere to be found in the early layers of the myth. In the original Phrygian story, Attis castrates himself under a pine tree and bleeds to death. Agdistis (a Great Mother figure) begs Zeus to restore him, but Zeus only grants a partial preservation.

According to the primary accounts found in Pausanias (Description of Greece 7.17.10-12) and later preserved by Arnobius (Adversus Nationes 5.7), Zeus only granted that Attis's body should not decay, his hair should continue to grow, and his little finger should move.

That isn't a resurrection; it's a glorified taxidermy.

It wasn't until much later—long after Christianity was already established—that the cult of Attis began to evolve and take on more "resurrection-like" themes. As the scholar A.T. Fear points out, the evidence for a "resurrection" of Attis only appears in the fourth century AD. By that time, it’s far more likely that the pagan cult was trying to compete with the burgeoning Christian movement by "borrowing back" some of its themes.

The Virgin Birth and the Pine Tree

The claim of a “virgin birth” collapses on contact with the sources. In the Attis myth, Nana becomes pregnant after an almond or pomegranate falls into her lap. This is not a virginal conception in any Jewish sense of the term. It is a piece of folkloric symbolism attached to a vegetation deity, not a historical claim about a human birth in first-century Judea. Treating the two as equivalent requires stripping both of their cultural context.

The same distortion appears in the claim that Attis was “crucified” or “died on a tree.” In the ancient accounts, Attis dies under a tree. That detail is then inflated into death on a tree, and finally rebranded as crucifixion. This is not comparison but semantic drift.

This is a clear example of what I have called, the Six Degrees of Jesus fallacy: superficial similarities are chained together until they resemble dependence. A tree becomes wood, wood becomes a cross, and proximity becomes execution. No historical connection is established, no textual borrowing is demonstrated, and no shared meaning is shown. The parallel exists only because it has been forced into existence.

Parallelism as a Tool of Dogma

Why does this myth persist? Because for a specific brand of dogmatic skepticism, the "copycat" narrative is too useful to let go. If you can convince someone that Jesus is just "warmed-over Phrygian myth," you don't have to deal with the historical evidence for the life of Jesus or the origins of the early Church.

But parallelism without evidence of direct influence is not history—it’s conspiracy theory with a thesaurus. The Attis "resurrection" is a modern invention, a reverse-engineered fantasy designed to debunk a faith by misrepresenting a myth.

Works Cited

- Arnobius. Adversus Nationes.

- Fear, A.T. "The Restoration of Attis." The Classical Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 1, 1996.

- Hurtado, Larry W. Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Eerdmans, 2003.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece.

- Vermaseren, M.J. Cybele and Attis: The Myth and the Cult. Thames and Hudson, 1977.