Who Really Removed Books from the Bible?

No, Constantine and the Catholic Church didn’t secretly edit the Bible. The canon emerged through centuries of messy debate, not some divine censorship committee.

TL;DR

No, Constantine didn't delete gospel chapters from his emperor lair. And the Catholic Church didn’t play divine librarian with red ink and a shredder. The biblical canon came together the old-fashioned way: with centuries of theological bickering, inconsistent lists, and a whole lot of scrolls.

A Meme Too Good to Die

The internet just can’t help itself. Every few weeks, a new post goes viral claiming the Bible we know was chopped, edited, and sanitized by shady church authorities with a thing for censorship. Constantine usually gets blamed, the Vatican always gets name-dropped, and some obscure "lost gospel" inevitably makes an appearance as the repressed truth they didn’t want you to see.

Let’s just say... the facts didn’t get the memo.

Did Constantine Edit the Bible?

Short answer: no. Constantine didn’t rewrite the Bible, and he certainly didn’t host some kind of divine book-burning party at the Council of Nicaea. That council—held in 325 CE—was about whether Jesus was of the same nature as God, not which books made the spiritual cut.

Biblical canon expert Lee Martin McDonald puts it plainly: "𝑇ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑒 𝑖𝑠 𝑛𝑜 𝑒𝑣𝑖𝑑𝑒𝑛𝑐𝑒 𝑓𝑟𝑜𝑚 𝑎𝑛𝑦 𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑖𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑠𝑜𝑢𝑟𝑐𝑒 𝑡ℎ𝑎𝑡 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝐶𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑐𝑖𝑙 𝑜𝑓 𝑁𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑒𝑎 𝑑𝑖𝑠𝑐𝑢𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑑 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑏𝑖𝑏𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑙 𝑐𝑎𝑛𝑜𝑛" (McDonald 214). The emperor’s contribution? He ordered some Bibles printed—based on what churches were already using. Not quite the conspiracy thriller.

Attis Didn’t Resurrect After Three Days

Asclepius and Jesus—The Resurrection That Wasn’t

From Sheol to Hell: How Afterlife Beliefs Evolved

Jesus vs Krishna: Stop Copying My Homework

So Who Actually Changed the Bible?

Here’s the twist that tends to catch people off guard: the Catholic Church didn’t remove books. In fact, it preserved them. The texts known as the "Apocrypha" or Deuterocanonical books—like Tobit, Judith, and 1 Maccabees—were widely read by early Christians and were officially affirmed at the Council of Trent in the 1500s.

Protestants were the ones who did some bookshelf rearranging. Martin Luther didn’t love certain theological themes, so he moved those books to the back of the Bible or left them out altogether. "𝐼𝑟𝑜𝑛𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑙𝑙𝑦, 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑢𝑠𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑠 𝑜𝑓 𝐶𝑎𝑡ℎ𝑜𝑙𝑖𝑐 𝑐𝑒𝑛𝑠𝑜𝑟𝑠ℎ𝑖𝑝 𝑜𝑣𝑒𝑟𝑙𝑜𝑜𝑘 𝑡ℎ𝑎𝑡 𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑡𝑒𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑡 𝑟𝑒𝑓𝑜𝑟𝑚𝑒𝑟𝑠 𝑚𝑎𝑑𝑒 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑚𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑠𝑖𝑔𝑛𝑖𝑓𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑛𝑡 𝑐ℎ𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑒𝑠 𝑡𝑜 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑏𝑖𝑏𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑙 𝑐𝑎𝑛𝑜𝑛" (Pelikan 76).

And those buzzy Gnostic gospels—Thomas, Mary, Judas? No one “removed” them. They were never part of the canon. Early church communities focused on texts with apostolic ties that were read publicly in worship. The Gnostic stuff? Fascinating, sure—but not a great fit theologically or liturgically. Still not a plot twist.

Why Do These Theories Stick Around?

Because “centuries of people arguing in Greek” doesn’t make for a sexy headline. "Conspiracy theories about biblical manipulation flourish because they provide simple answers to complex historical processes" (Brakke 58). And honestly? The truth is kind of a slog.

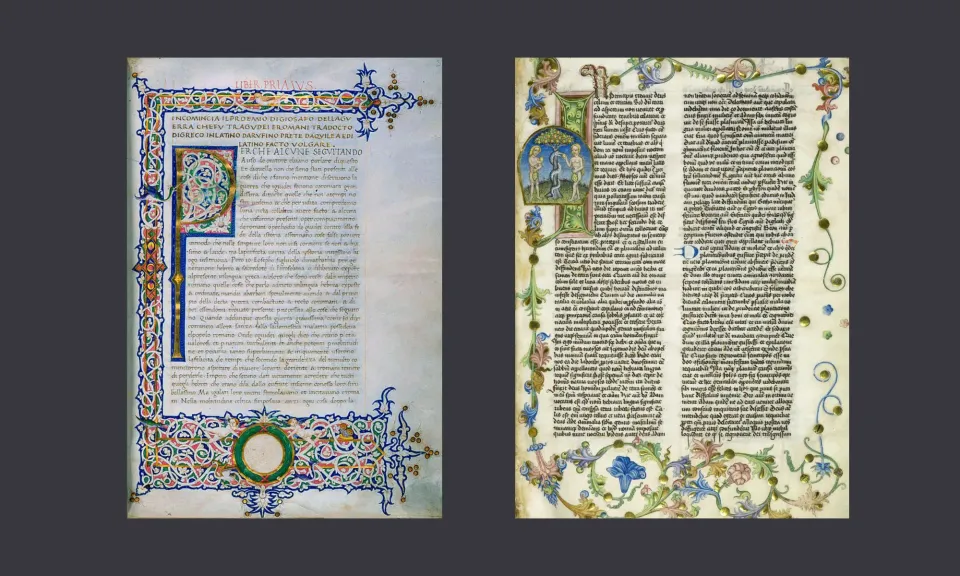

Plus, there’s something irresistible about “forbidden knowledge.” People love the idea that they’ve uncovered something the powers-that-be tried to bury. But as scholar Michael Kruger notes, "The canon was not formed by top-down decrees alone, but by widespread consensus over centuries" (Kruger 127). Not exactly a secret scroll in a locked vault. More like a lot of letters, meetings, and very old paper.

A Timeline of How the Canon Actually Came Together

c. 140 CE – Marcion proposes a slimmed-down canon, triggering debates

c. 180 CE – Irenaeus defends the four-Gospel lineup

c. 200 CE – Muratorian Fragment lists early accepted texts

c. 250 CE – Origen comments on disputed and accepted writings

367 CE – Athanasius lists all 27 New Testament books in a festal letter

382 CE – Council of Rome backs Athanasius’s list

393/397 CE – Hippo and Carthage councils cement the canon for Western Christianity

1545–1563 CE – Council of Trent reaffirms the Deuterocanonical books

1534 CE – Luther moves some books to an appendix

1647 CE – Westminster Confession excludes them entirely

Conclusion: Less Conspiracy, More Committee Meeting

If you were hoping for a Vatican thriller or a sword-wielding emperor slashing gospels out of existence, sorry to disappoint. The real story? Tedious, complicated, and deeply human. The biblical canon didn’t come from a master plan—it emerged from communities reading, arguing, praying, and disagreeing over centuries.

So no, the Church didn’t rip out pages, and Constantine wasn’t moonlighting as a script doctor. But if you’re looking for drama, don’t worry—the canon story has enough slow-burn chaos to satisfy even the most devoted history nerd.

Works Cited

Brakke, David. The Gnostics: Myth, Ritual, and Diversity in Early Christianity. Harvard University Press, 2010.

Bruce, F. F. The Canon of Scripture. InterVarsity Press, 1988.

Kruger, Michael J. Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament Books. Crossway, 2012.

McDonald, Lee Martin. The Formation of the Biblical Canon: Volume 2. Hendrickson Publishers, 2007.

Metzger, Bruce M. The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance. Oxford University Press, 1987.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Reformation of the Bible/The Bible of the Reformation. Yale University Press, 1996.