The Gods of Israel: From Many to One

Before Israel worshiped one God, it worshiped many. Archaeology reveals that Yahweh once shared divine space with Asherah — the goddess who refused to disappear quietly.

(Bible as History — Part II)

Before Israel worshiped one God, it worshiped many. The dirt still says so.

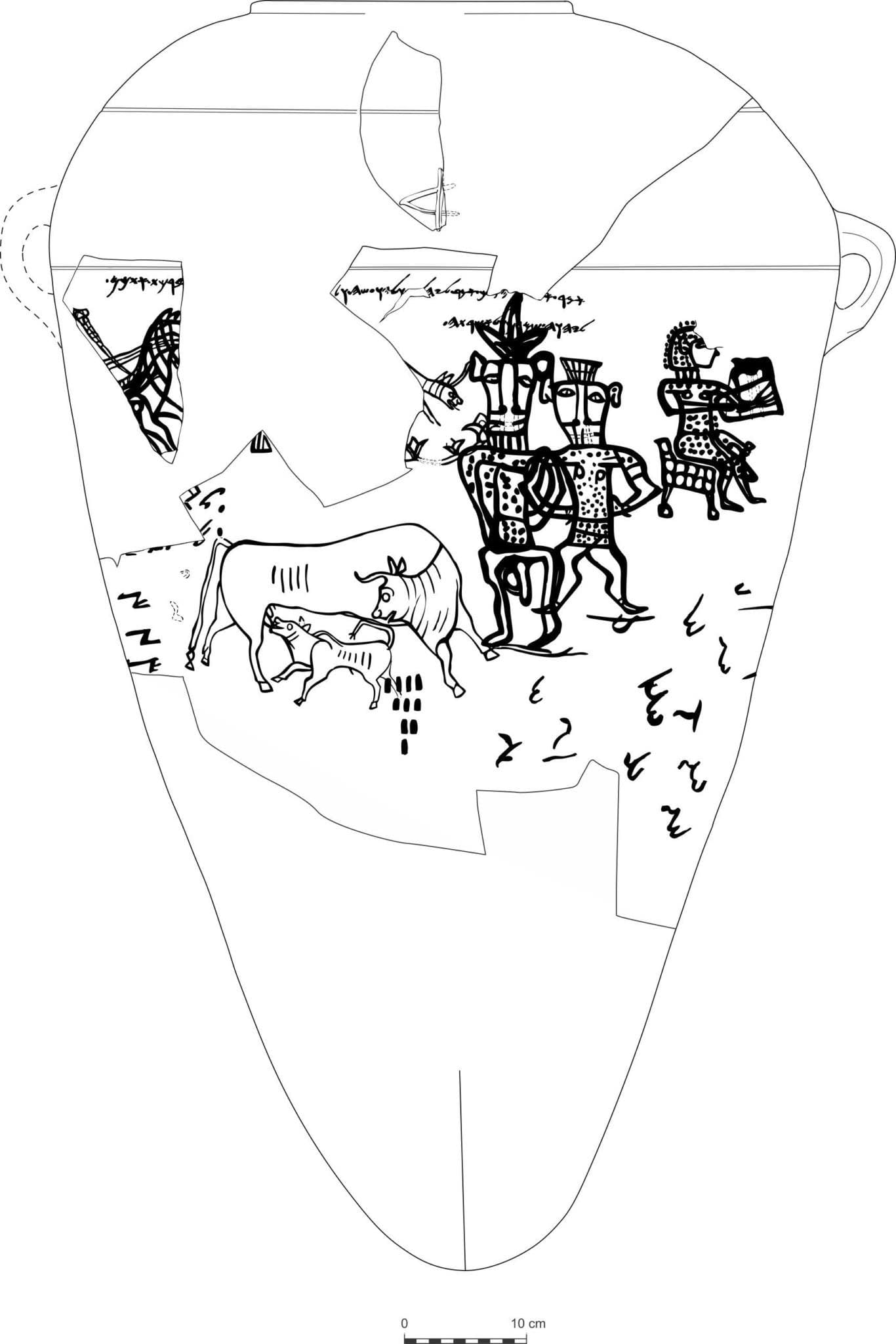

Fragments of pottery from a remote Sinai outpost bear an inscription that reads, “Yahweh and his Asherah.” Another, carved into the wall of a tomb at Khirbet el-Qom, blesses a man “by Yahweh and his Asherah.” Archaeologists unearthed hundreds of female clay figurines from Judahite homes—broad-hipped, hands cupping their breasts, mass-produced symbols of divine fertility. These are not relics of a tiny heretical fringe; they were mainstream religion. The people of Israel and Judah once prayed to a divine family, not a solitary king in heaven.

The biblical writers, of course, couldn’t leave that standing.

The Forgotten Gods

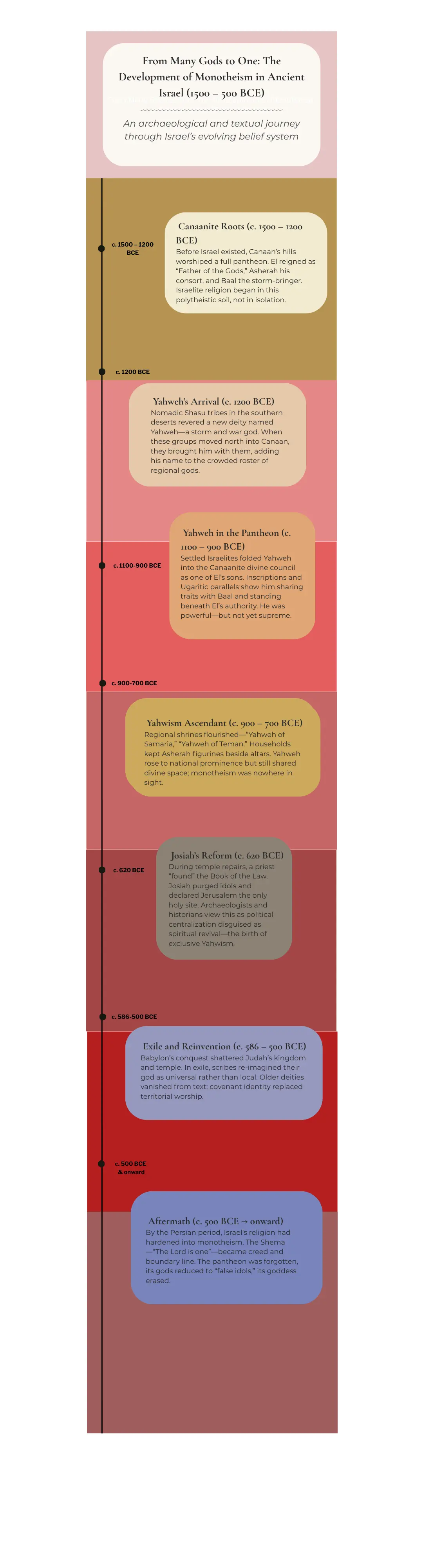

In the Late Bronze and early Iron Ages, the highlands of Canaan were filled with small shrines to the gods of the region: El, Baal, Anat, Asherah, and Yahweh among them. Ugaritic tablets—unearthed at Ras Shamra—reveal a pantheon ruled by El, “father of gods,” whose consort was Asherah, “Lady of the Sea.” Yahweh, however, was not part of that northern pantheon. He began as a southern storm-and-war deity worshiped by desert tribes known as the Shasu. When these groups moved north and settled in Canaan, they introduced Yahweh into the local religious landscape. Yahweh became absorbed in the pantheon of gods worshiped by the ancient Israelites as part of the Canaanite divine family. In some parts of the Old Testament, Yahweh and El are referred to as separate individuals, but we can see the evolution in the Bible passages where eventually Yahweh and El merged into one superhero god, and the attributes of El were passed on to Yahweh—as was the wife of El.

Kuntillet Ajrud inscription (“Yahweh and his Asherah”), Sinai Peninsula, 8th century BCE. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Detail showing the couple labeled “Yahweh and his Asherah” on the Kuntillet Ajrud inscription.

By the 9th and 8th centuries BCE, the religion of Israel had coalesced into what scholars call Yahwism: a national cult that recognized Yahweh as chief among the gods but not yet the only one. Households still kept Asherah idols; regional sanctuaries honored Yahweh under local epithets—Yahweh of Samaria, Yahweh of Teman, Yahweh of Shomron. Polytheism was normal, not rebellion.

Female clay “pillar figurines” from Judahite homes, Jerusalem. Israel Museum collection.

The “Discovery” of the Law

Then the narrative shifts—from archaeology to propaganda.

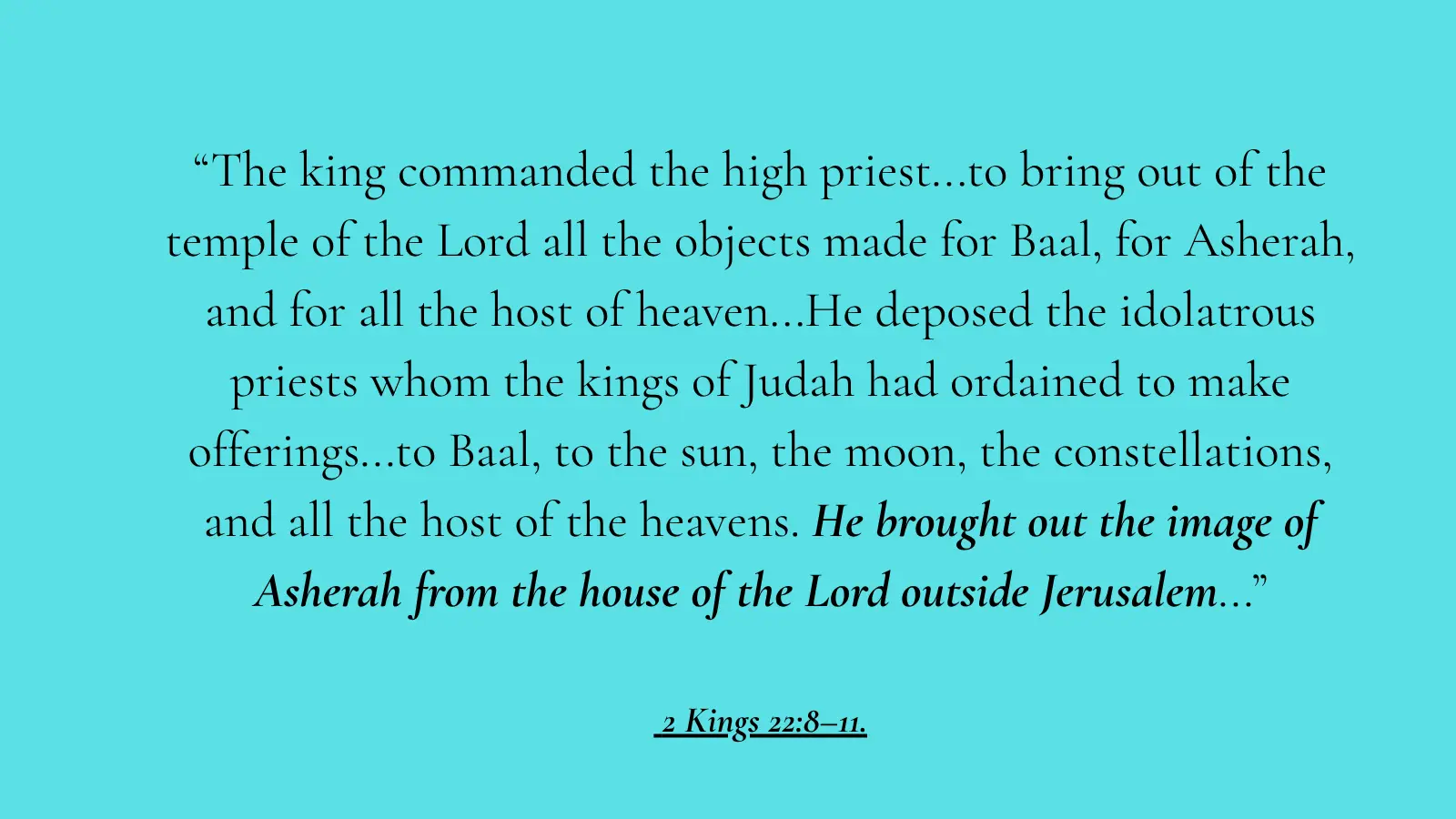

According to 2 Kings 22–23, during repairs to the Jerusalem temple, the priest Hilkiah “found the Book of the Law.” King Josiah read it, tore his clothes in shock, and launched a ferocious purge:

The story insists the people had forgotten the Law entirely, as if a nation that once built a temple for Yahweh somehow lost every copy of his covenant until a lucky priest rediscovered it in a broom closet. Historically, that makes no sense. We are told in the text that Josiah’s great-grandfather had done “right in the sight of the Lord,” which indicates that the people had not forgotten anything at all.

What Josiah “found” was almost certainly a newly composed or heavily edited form of Deuteronomy — a manifesto calling for exclusive worship of Yahweh in one place: Jerusalem. The reform that followed was a political revolution disguised as repentance. Later editors recast his campaign as a return to lost truth, rather than what it was: the invention of monotheism to centralize political and religious power in Jerusalem—a stark contrast to the decentralized worship that preceded this “reform.”

The Sin That Wasn’t

Kings and Chronicles turn this history into a morality play. Each ruler is judged by whether he “did right in the sight of the Lord” or “did evil,” meaning whether he tolerated other gods. The constant cycle—apostasy, punishment, repentance—reads like theology, but underneath it lies a very human process: the rewriting of memory. What the ancestors once practiced freely became, in retrospect, idolatry.

The authors did not discover that Israel had been monotheist all along; they decided it had to have been. To maintain that fiction, they painted centuries of ordinary religion as betrayal and cast their own reforms as a divine rediscovery.

The Long Shadow of Asherah

Even after the purges, the goddess lingered. The prophets still rail against “the Asherim.” The household figurines persist until the Babylonian exile. Only after that trauma does the written tradition harden into monotheism. The Shema—“Hear, O Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord alone”—is not a memory of the past; it is a reaction to it.

The first commandment does not forbid foreign gods because no one believed in them. It forbids them because everyone did.

Works Cited

Dever, William G. Has Archaeology Buried the Bible? Eerdmans, 2020.

Finkelstein, Israel, and Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Free Press, 2001.

Pardee, Dennis. Ras Shamra and the Ugaritic Texts. Society of Biblical Literature, 2002.

Zevit, Ziony. The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches. Continuum, 2001.

© 2025 The Hatchetman Atheist. All rights reserved.