Myth-Information: How the Flood Story Got Bigger, Wetter, and Theologically Deeper

TL;DR

The biblical flood didn’t drop out of the sky. It evolved from much older Mesopotamian myths that were regional, chaotic, and mostly devoid of moral stakes. Over time, as civilizations expanded and theology deepened, the flood got bigger, wetter, and more judgmental—culminating in the global deluge of Genesis.

Introduction: The Original Disaster Movie

It is commonly known that the story of Noah’s flood is inextricably related to the earlier flood story in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Long before Noah was bobbing in a floating zoo, ancient Near Eastern civilizations were already writing about catastrophic floods. But the original versions weren’t so dramatic. The earliest flood stories were local—stories of regional chaos, not global annihilation. Over centuries, these myths evolved, expanding in both scale and significance until they culminated in the all-encompassing global judgment seen in the Book of Genesis.

As mythologist Andrew George observes, "The trajectory from Sumerian to Hebrew flood stories reflects an inflationary trend: geographically, morally, and theologically" (George 88). In other words, the myth got bigger as the civilizations telling it got bigger. Let's trace that transformation.

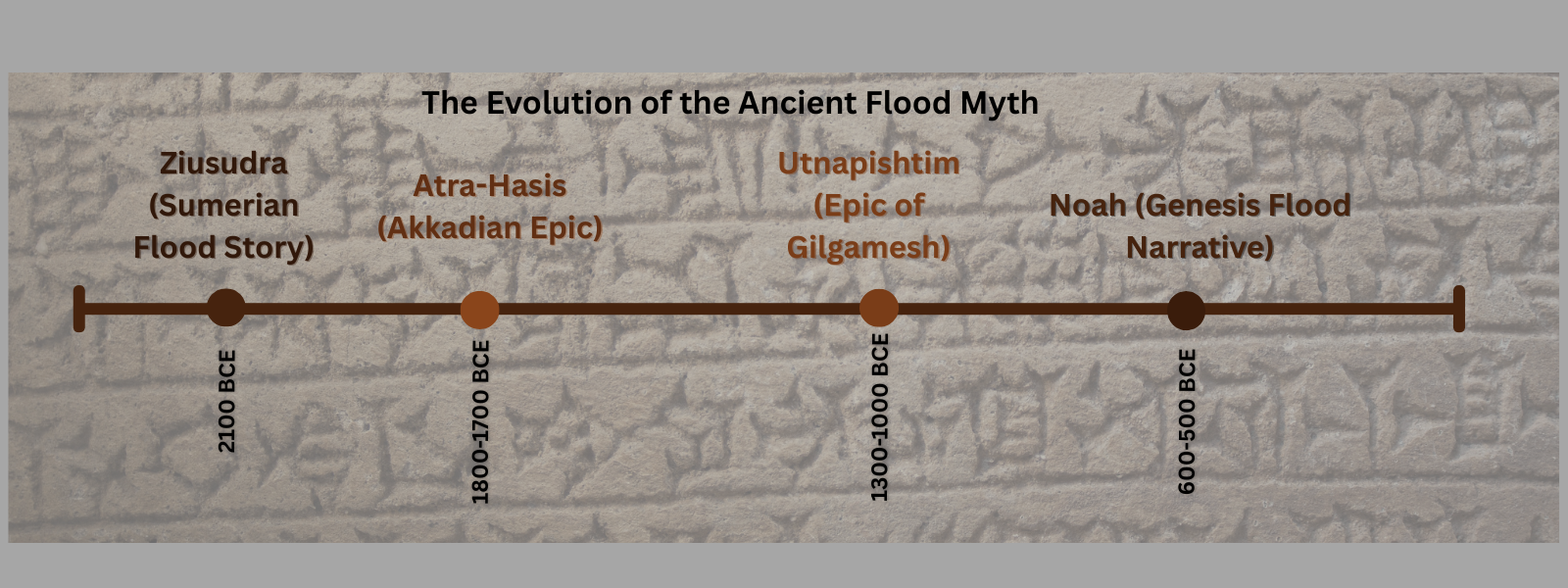

Track how the flood story evolved across four major texts over 1,500 years.

The Sumerian Flood: A Regional Event, Not the End of the World

The earliest flood narrative on record is the Sumerian Flood Story, dating to around 2100 BCE. In it, a righteous king-priest named Ziusudra receives a divine warning about a coming deluge. He builds a boat, survives, and is granted eternal life by the gods. But there’s no mention of universal destruction or a moral reckoning—just a local flood impacting a specific region.

Historian Judith Giannini explains, "There is no suggestion that the entire earth was affected—only the known world of the Sumerians, essentially the floodplain of the lower Tigris-Euphrates Valley" (Giannini 5). Even the Sumerian King List treats the flood not as a global crisis but as a historical boundary: "Then the flood swept over, and kingship was taken to Kish" (ETCSL 2.1.1).

This isn’t cosmic judgment. It’s a major inconvenience.

The Origins of the Hebrews: From Canaan to Yahweh

Ezekiel’s Prophecy About Tyre Didn’t Happen

Josiah’s Reform: Religion, Power, and Lost Scripture

Who Really Wrote the Torah? A Literary Patchwork Unveiled

From Sheol to Hell: How Afterlife Beliefs Evolved

Parallelism: Because Apparently Everything Is a Copy of Something

Akkadian Atra-Hasis: The Gods Get Petty

A few centuries later, the Akkadian myth of Atra-Hasis (ca. 1800–1700 BCE) introduces more divine drama. Here, the gods decide to flood humanity because people are too noisy. The chief god Enlil is irritated, while Enki—always the laid-back one—warns Atra-Hasis and instructs him to build a boat.

Stephanie Dalley points out that, "The gods, especially Enlil, are temperamental and disorganized, and their decision to flood humanity lacks moral depth—it is administrative, not ethical" (Dalley 32). In short, the flood is still not about sin or corruption. It’s about noise complaints.

And the scope? Still local. The text refers to flooding farmland and city areas, not obliterating the globe.

Gilgamesh: Same Flood, Better Writing

By the time we reach the Epic of Gilgamesh (1300–1000 BCE), the flood myth has been refined into high art. Utnapishtim (the Akkadian version of Atra-Hasis) recounts his survival to Gilgamesh. This version adds divine remorse, a bird-release sequence, and poetic flair. But it still doesn’t globalize the event.

Andrew George writes, "Utnapishtim’s flood submerges the Mesopotamian world, not the physical globe. The language is stylized, not topographic" (George 91). The gods overreact, regret it, and grant Utnapishtim immortality—a divine apology for excessive rainfall.

Genesis: The Moral Flood Goes Global

The Genesis narrative (compiled around 600–500 BCE) marks the turning point. Now the flood is explicitly global, and the cause is moral failure. God sees that the earth is corrupt and violent, and decides to start over.

"For my part, I am going to bring a flood of waters on the earth, to destroy from under heaven all flesh in which is the breath of life" (Genesis 6:17, NRSVue).

This isn’t divine frustration—it’s divine justice. The monotheistic worldview of Genesis gives the flood new gravity: one righteous man, one God, one earth, one clean slate.

Tikva Frymer-Kensky explains, "Genesis transforms a Babylonian survival myth into a theological treatise: sin brings judgment, but righteousness brings covenant" (Frymer-Kensky 121). The flood now serves a doctrinal function, not just a narrative one.

Evidence That Early Floods Were Not Global

Despite the grandeur of later versions, there is no evidence the earliest flood myths were meant to describe a global event:

- Ziusudra's flood affects the lower Tigris-Euphrates, not the planet (Giannini 5).

- Atra-Hasis speaks of localized damage to cities and farmland (Dalley 34).

- Utnapishtim lands on a mountain in the north, not atop the cosmic axis (George 90).

Only Genesis makes the leap to a flood that erases all terrestrial life. That leap is both theological and literary, rooted in a monotheistic vision of divine order and cosmic justice.

George calls this phenomenon "mythic escalation," noting, "As empires grow, so do their gods—and so do their floods" (George 92).

Modern scholarship dates the Genesis flood account to the post-exilic period, when Israelite theology was undergoing significant revision.

Why the Flood Got Bigger

Several cultural forces drove the inflation of the flood myth:

- Empires grew, and with them, the concept of “the world” expanded.

- Theological narratives demanded more dramatic stakes and consequences.

- Competing civilizations used myth to assert spiritual superiority.

As Irving Finkel puts it, "The flood was not merely an event, but a medium through which different civilizations expressed what they feared—and what they believed made life worth saving" (Finkel 47).

Conclusion: From Local Storm to Global Statement

The flood myth began as a local story, reflecting regional disasters that shaped the lives of ancient Mesopotamians. Over time, the myth grew—becoming more poetic, more moral, and ultimately more apocalyptic. By the time Genesis was written, the flood wasn’t just a downpour. It was divine reset.

The flood got bigger because the story needed to be bigger. And the story needed to be bigger because the civilizations telling it were now asking bigger questions—about justice, order, and survival.

Timeline of Ancient Flood Stories

- ca. 2100 BCE – Sumerian Flood Story (Ziusudra)

Appears in fragments from Nippur; describes a localized flood affecting Sumerian cities. No global scope, no sin-based motivation. - ca. 1800–1700 BCE – Atra-Hasis Epic (Akkadian)

Features a more dramatic narrative; gods flood the earth due to human noise. Still regional in scope, but introduces the theme of divine regret. - ca. 1300–1000 BCE – Epic of Gilgamesh (Babylonian)

Incorporates a poetic and expanded version of the flood story. Utnapishtim survives, and the gods regret their decision. The scale is large, but still not global. - ca. 600–500 BCE – Genesis Flood Narrative (Hebrew)

A full theological reboot. God floods the entire earth due to human wickedness. Moralized, monotheistic, and global in scope. Most scholars place its composition or final redaction during or after the Babylonian exile.

Works Cited

Dalley, Stephanie. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford UP, 2000.

Finkel, Irving. The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood. Hachette UK, 2014.

Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. Reading the Women of the Bible. Schocken Books, 2002.

George, Andrew. The Epic of Gilgamesh: The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian. Penguin Classics, 2003.

Giannini, Judith. Perspective on Dating the Sumerian Great Flood and Hypothetical Reconstruction of Events. European Journal of Applied Sciences, 2024. Link

Kramer, Samuel Noah. History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Recorded History. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1981.

The Bible. New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition, NRSVue, Harper Bibles, 2022.

Comments ()