The Origins of the Hebrews and Yahweh

The Hebrews didn’t appear overnight. They arose from Canaanite farmers and desert nomads, blending culture, language, and religion. Their god Yahweh wasn’t a bolt from the blue—he was part of a long evolution from El, shaped by syncretism and reform.

Key Insights: The Hebrew Synthesis

- Not an Overnight Origin: Early Israelite identity was a slow "slow burn," not a sudden event. It was a fusion of local Canaanites and desert nomads.

- The DNA of Culture: Early Hebrew pottery, architecture (the four-room house), and language were all local Canaanite evolutions.

- The Diet Marker: The absence of pig bones in highland sites serves as one of the earliest archaeological "ethnic markers" for the group.

- The Great Merger: Yahweh likely originated in the southern deserts (Midian/Edom) and slowly "absorbed" the traits of the Canaanite creator-god, El.

- The Asherah Factor: For centuries, many Israelites worshipped Yahweh alongside a consort, the goddess Asherah, before strict monotheism took hold.

The story of the ancient Hebrews is less about a single, dramatic moment of origin and more about a long, gradual process of identity formation. Archaeology and historical texts reveal that early Israel didn’t appear overnight. Instead, it grew out of local and regional dynamics in Canaan and its neighboring deserts. Two main theories explore these roots: one sees the Hebrews as emerging from within Canaanite society; the other suggests they came from outside, bringing new cultural and religious elements with them.

Where did the Hebrews come from?

Mainstream models: Canaanite origins, ruralization, and why the “conquest” tale reads like later mythmaking.History of the Hebrews

A fast timeline from Iron Age hill tribes to Second Temple Judaism—minus the Sunday-school varnish.Canaanite-Origin Theory

One widely supported theory holds that the ancient Hebrews were originally Canaanites who gradually developed a distinct identity. Archaeological surveys have uncovered over 300 small villages in the highlands of Canaan, dated to Iron Age I (c. 1200–1000 BCE), in areas previously uninhabited. These settlements weren’t marked by massive new structures or foreign artifacts—instead, their pottery, architecture, and layout closely resemble that of late Bronze Age Canaanite cities (Dever 45). Even the common four-room house design used by Israelites appears to be an evolution of Canaanite domestic styles.

The continuity extends to language. Hebrew was not a linguistic transplant but a Canaanite dialect, part of the Northwest Semitic language family along with Phoenician and Moabite. This suggests that early Israelites were essentially local people, adapting to new social conditions. Some scholars suggest that economic instability at the end of the Bronze Age pushed rural Canaanites to abandon city life and form egalitarian, clan-based communities in the hills. Their material culture reflected simplicity and self-sufficiency: modest homes, communal grain silos, and an absence of elite tombs or luxury imports (Finkelstein and Silberman 108).

Nomadic-Band Theory

The alternative theory posits that some of the early Israelites came from outside Canaan, likely as nomadic or seminomadic herders from the deserts to the south and east. This theory draws partly on biblical traditions—stories of Abraham's migration and the Exodus from Egypt, for instance—which preserve a memory of outside origins. Archaeologist Albrecht Alt proposed that these groups didn't invade but slowly infiltrated, settling peacefully in the highlands.

Archaeological signs support this scenario. Early highland settlements often lack pig bones, contrasting sharply with lowland Canaanite and Philistine sites where pork was common (Sapir-Hen et al. 4). This may reflect a food taboo rooted in pastoral nomadic culture, where pigs were impractical to raise. While recent evidence complicates this picture, the early Iron Age pattern is consistent: the highland settlers identified as different, and avoiding pork became part of that distinction.

Other clues include architectural features like the four-room house, possibly evolved from nomadic tent layouts, and the appearance of collared-rim storage jars that also show up east of the Jordan. Linguistically, Hebrew shares some affinities with Transjordanian dialects, such as Moabite and Aramaic, suggesting connections with groups from that region. The nomadic-band theory doesn't reject the Canaanite element; rather, it proposes a fusion of indigenous farmers and incoming herders that led to Israelite identity.

Material Culture: Continuity and Change

In material terms, early Israelite culture looked a lot like Canaanite culture with a few notable shifts. Pottery from Israelite sites continues Bronze Age traditions. The four-room house becomes a hallmark of Israelite villages, but its roots are Canaanite. The differences lie in what’s missing: pigs, palaces, temples, and elite luxury goods. Israelite communities were small, rural, and egalitarian.

Perhaps the clearest ethnic marker is diet. Archaeozoological studies confirm that early Israelites avoided pork, which may have helped define their identity against Philistines and Canaanites (Sapir-Hen et al. 6). This wasn’t just practical; it may have been ideological.

Religious practices also reflect a transitional phase. A 12th-century BCE altar site in the Samarian highlands—the so-called "Bull Site"—featured a bronze bull figurine, a symbol of the Canaanite god El. This suggests that early Israelite worship drew on Canaanite religious imagery but operated outside the established temple system (Dever 76).

Religious Developments: From Polytheism to Monotheism

Early Israelite religion emerged within the broader Canaanite religious world. The Canaanite pantheon included El (the creator god), Baal (storm god), Asherah (mother goddess), Astarte (fertility), and others. Initially, Israelites worshipped El as their chief deity—as reflected in the name Isra-el, meaning "El rules" or "El strives."

The adoption of Yahweh was a turning point. Yahweh does not appear in Canaanite texts, suggesting he came from outside. An Egyptian inscription from the 14th century BCE mentions "Yahu" in the land of the Shasu nomads of Edom or Seir, possibly referring to Yahweh. The Bible echoes this origin: Moses meets Yahweh for the first time in Midian (Exod. 3), through his Midianite priest father-in-law. The Song of Deborah also describes Yahweh as coming from Seir and Edom (Judg. 5:4).

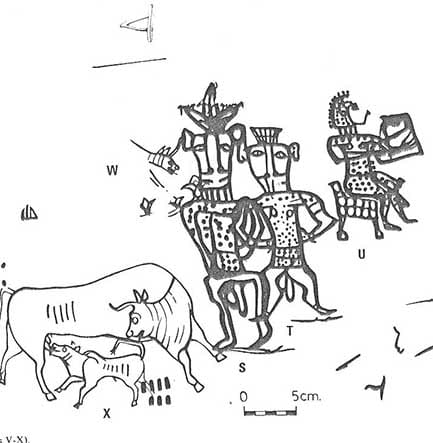

Over time, Yahweh took on roles previously associated with El. Scholars see this as a religious merger: Yahweh absorbing El’s identity and becoming the national god. Asherah, who was originally El’s consort, also continued to be worshipped. Inscriptions from sites like Kuntillet Ajrud bless individuals in the name of "Yahweh and his Asherah" (Smith 48). Figurines found across Israelite settlements suggest she remained a popular goddess well into the monarchy period.

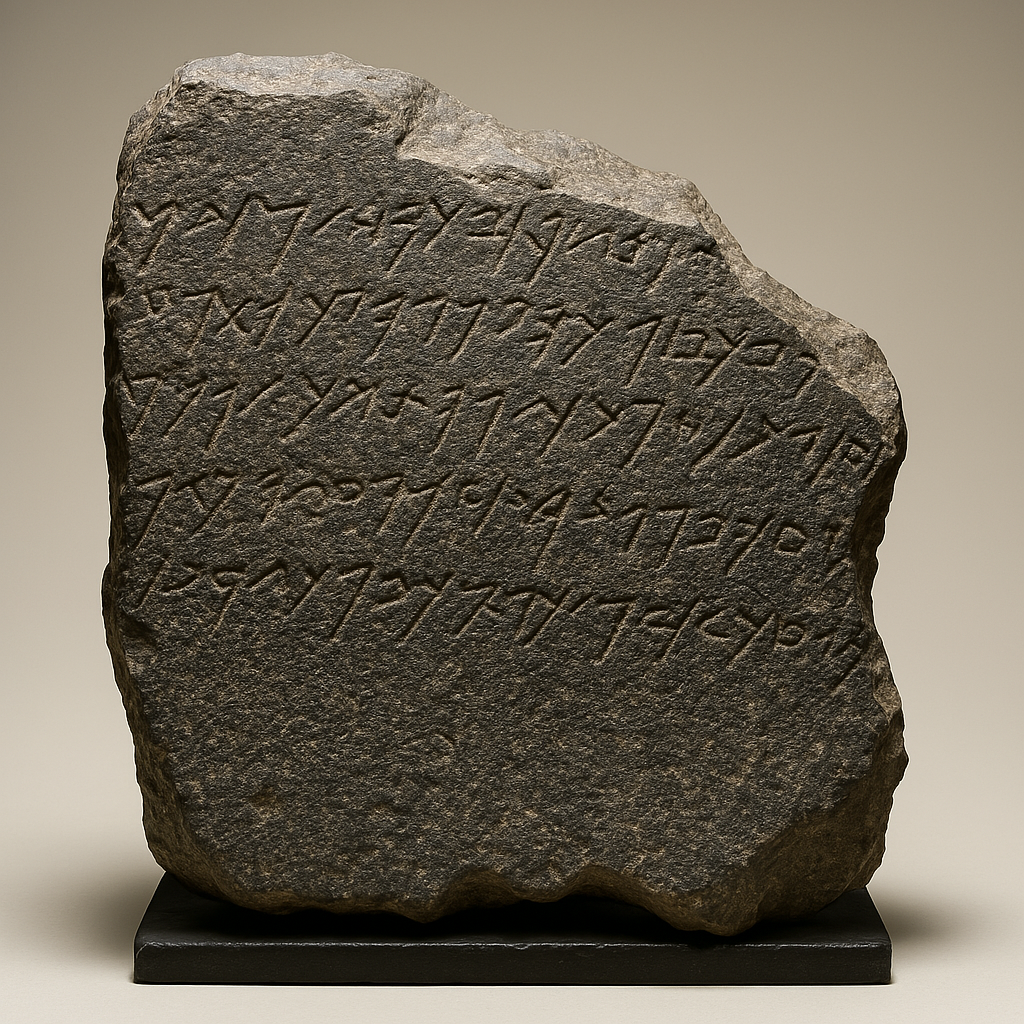

The merging of Yahweh and El was part of a broader pattern of syncretism. Israel didn’t suddenly break with Canaanite religion; it gradually reinterpreted and refocused it. Even other Canaanite groups may have included Yahweh in their pantheons. The Mesha Stele, a 9th-century Moabite inscription, acknowledges Yahweh as Israel’s god.

The persistence of other deities alongside Yahweh reflects a henotheistic or monolatrous phase: worshipping one god above others but not denying their existence. Biblical texts frequently condemn the worship of Baal and Asherah, indicating how widespread it was. Reformers like Elijah and Josiah eventually pushed for exclusive Yahweh worship, leading to the monotheism that would define later Judaism. In exile, prophets proclaimed: "I am the LORD, and there is no other" (Isa. 45:5, NRSVue).

Theophoric names reflect this transition. Early Israelite names often invoke El—Gabri-el, Micha-el.—but later names favor Yahweh: Yehoshua (Joshua), Yirmeyahu (Jeremiah), Yesha'yahu (Isaiah). This practice was common in other cultures as well. Egyptians named children after deities like Amun or Ra (e.g., Tutankhamun), and Mesopotamians did the same with gods like Nabu and Ashur (e.g., Ashurbanipal).

Conclusion

The origins of the ancient Hebrews can’t be pinned to a single migration or dramatic divine encounter. They arose from a mix of Canaanite villagers, desert nomads, and shifting religious ideas. Their material culture started off nearly indistinguishable from Canaanite life. Their language, homes, and gods bore familiar forms. But subtle shifts—in diet, settlement patterns, and religious symbols—started to set them apart. Yahweh emerged from the deserts and eventually took the center stage, replacing El and becoming the sole focus of worship. What began as a blended, polytheistic faith slowly evolved into something new. The Hebrews didn’t invent a religion from scratch; they transformed what they inherited. And in doing so, they helped reshape the spiritual landscape of the world.

FAQ

Where did the Hebrews come from? Most scholars see Canaanite roots with hill-country settlement and social change, not an outside invasion.

Is the conquest story historical? Archaeology doesn’t support it as written; it reads like later national mythmaking.

When does “Israelite” identity emerge? Iron Age I–II, as hill tribes consolidate and later temple-centered Judaism forms.

What sources matter most? Archaeology, epigraphy, and careful reading of the biblical texts in context.

Works Cited

Dever, William G. Did God Have a Wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Eerdmans, 2005.

Finkelstein, Israel, and Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Free Press, 2001.

Sapir-Hen, Lidar, et al. "Pig Husbandry in Iron Age Israel and Judah: New Insights Regarding the Origin of the 'Taboo'." Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins, vol. 129, no. 1, 2013, pp. 1–20.

Smith, Mark S. The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel. 2nd ed., Eerdmans, 2002.