Is Human and Chimp DNA 95% or 99% Identical?

Is human/chimp DNA 95% or 99% similar? Both are true! Learn the simple science behind the two different ways biologists measure our genetic relationship.

The Science Behind the Stats

Table of Contents

- The Cheat Sheet for the Impatient

- The Argument That Never Ends

- The Instruction Manual Metaphor

- Method 1: The Spelling Test (98.8%)

- Method 2: The Page Count (95%)

- Why the Gap Matters (The 1.2% Secret)

- Why the Confusion Persists

- FAQ: The Quick Rundown

- Works Cited

The Cheat Sheet for the Impatient

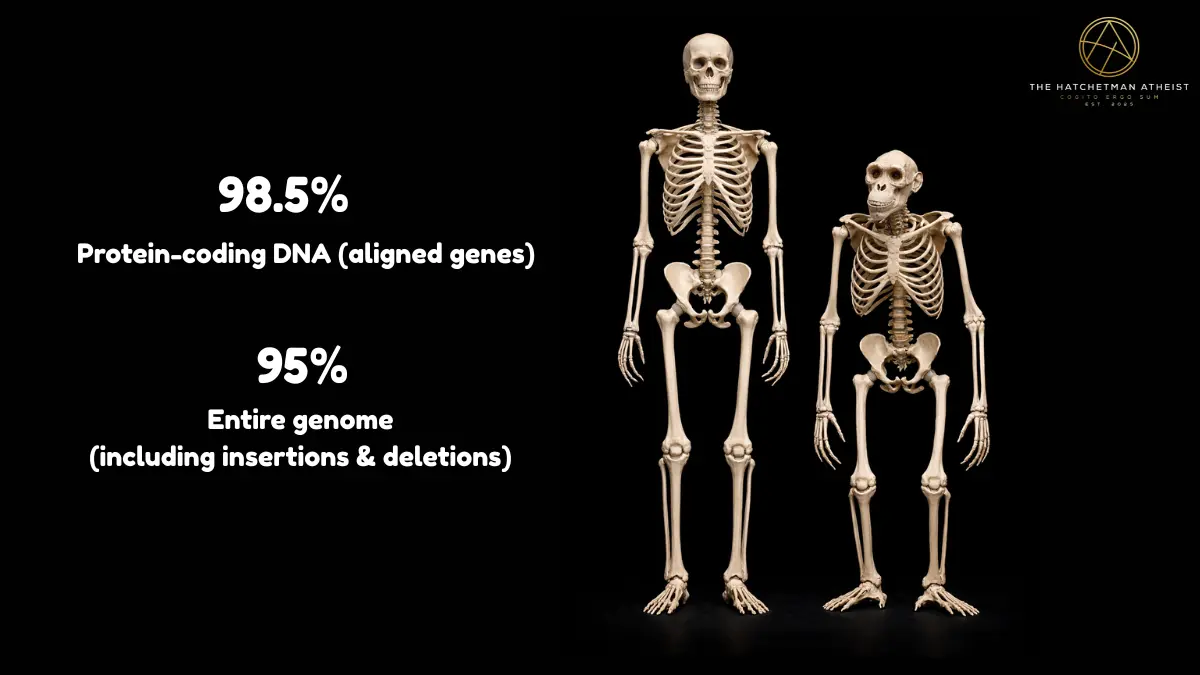

98.8 percent

Measures spelling.

This compares shared protein-coding genes, lined up letter by letter.

95 percent

Measures total volume.

This includes insertions, deletions, repeats, and DNA that exists in one genome but not the other.

The verdict

Both numbers are scientifically accurate. They are not competing facts. They are different measurement rules applied to the same genomes.

The Argument That Never Ends

If you have spent any time in the evolution versus creationism trenches, you have seen this exchange play out with ritualistic precision.

Person A: Humans and chimps are 98.8 percent genetically identical.

Person B: Actually, modern science says it’s only 95 percent. Stop using outdated propaganda.

Conversation over. Internet points awarded. Reality ignored.

Here is the part that almost never gets mentioned: the scientists responsible for the 98.8 percent figure are often the same researchers who also describe the 95 percent figure. They are neither confused nor retreating from earlier conclusions. They are simply measuring different aspects of the genome.

This is not a scientific dispute. It is a rhetorical one.

The Instruction Manual Metaphor

DNA can be thought of as an instruction manual, provided we remember that it is a very strange one. It contains clear instructions, duplicated paragraphs, obsolete sections, and long stretches that appear to do nothing at all.

If you wanted to compare the human manual to the chimpanzee manual, you would first need to decide how the comparison works. There are at least two reasonable options.

One focuses on shared instructions.

The other counts everything, including extra pages and missing chapters.

Each method produces a different percentage, and neither is wrong.

A plain-language introduction to genes, chromosomes, and why DNA comparisons work the way they do.

Method 1: The Spelling Test (98.8%)

In this method, scientists use a process called

genetic alignment.

A gene in the human genome is matched with its corresponding partner in the chimpanzee genome. Any DNA that cannot be confidently paired is set aside.

Only the shared, functional genes are compared.

Once aligned, researchers compare the letters themselves. Out of every thousand DNA bases, roughly 988 are identical. This is why the landmark 2005 Nature paper concluded that humans and chimpanzees are 99 percent identical at

orthologous nucleotide sites.

Human manual: Build a large frontal lobe here.

Chimp manual: Build a barge frontal lobe here.

The typo exists, but the instruction still works. As a result, immune systems, skeletal structures, and metabolic processes operate almost exactly the same way.

This measurement answers a specific question: how similar are the working biological instructions?

Method 2: The Page Count (95%)

Now remove the filters.

Instead of comparing only shared genes, imagine counting every page in both manuals.

What if the chimp genome contains large DNA segments that humans lack entirely?

What if humans have duplicated regions that chimps carry only once?

These insertions and deletions, known as

indels,

matter structurally even when they do not affect protein-coding genes. When they are counted as differences, overall similarity drops to about 95 percent.

This approach measures genomic landscape rather than spelling. It answers a different question: how similar are the total DNA contents, including extra and missing material?

Roy Britten’s analysis explicitly includes these indels. It does not contradict earlier gene-based studies. It complements them.

Why the Gap Matters (The 1.2% Secret)

If humans and chimpanzees share so much DNA, why are we not interchangeable?

Because much of the difference lies in regulation rather than raw components. These are genetic dimmer switches that control when, where, and how long genes are active.

Brain development provides a clear example. Humans and chimpanzees possess nearly the same brain-building genes. The difference is timing. In humans, those genes remain active longer during childhood, allowing extended neural growth.

Another example involves the MYH16 gene. A small mutation weakened jaw muscles in the human lineage, reducing mechanical constraints on skull expansion. The result was room for a larger brain, not a redesigned genome.

Tiny changes. Outsized consequences.

How shared viral scars in our DNA reveal deep evolutionary history.

Why the Confusion Persists

Inside the laboratory, there is no controversy. Researchers treat these percentages as different analytical lenses.

Outside the lab, numbers become weapons.

The 95 percent figure is often presented as a correction or exposure, implying that evolutionary biology quietly walked back its claims. In reality, both figures emerged from the same era of genomic research and are frequently cited together.

Even at 95 percent similarity, humans are more closely related to chimpanzees than horses are to zebras. No amount of arithmetic rescues the idea of separate origins.

What happens when claims meet data instead of slogans.

FAQ: The Quick Rundown

Is the 95 percent number a correction of the 98.8 percent number?

No. One measures nucleotide substitutions in aligned genes. The other includes insertions and deletions across the whole genome.

Which number should I use in a debate?

If you are discussing physiology or medicine, 98.8 percent is standard. If you are discussing total genomic structure, 95 percent is appropriate.

Does this similarity mean humans evolved from chimps?

No. Humans and chimpanzees share a common ancestor. We are evolutionary cousins, not descendants.

Works Cited

Britten, Roy J. “Divergence between Samples of Chimpanzee and Human DNA Sequences Is 5% Counting Indels.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 99, no. 21, 2002, pp. 13633–13635.

Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium. “Initial Sequence of the Chimpanzee Genome and Comparison with the Human Genome.” Nature, vol. 437, no. 7055, 2005, pp. 69–87.

Pollard, Katherine S. “What Makes Us Different?” Scientific American, vol. 300, no. 5, 2009, pp. 44–49.

Salzberg, Steven L. “Genome Reannotation: A Welcome Change.” Genome Biology, vol. 8, no. 1, 2007, p. 102.

Stedman, Hansell H., et al. “Myosin Gene Mutation Correlates with Anatomic Changes in the Human Lineage.” Nature, vol. 428, no. 6981, 2004, pp. 415–418.

Varki, Ajit, and Tasha Altheide. “Comparing the Human and Chimpanzee Genomes: Searching for Needles in a Haystack.” Genome Research, vol. 15, no. 12, 2005, pp. 1746–1758.