What Happens in the Brain During an NDE (Near-Death Experience)

The claim that NDEs prove consciousness survives death relies on a medical misunderstanding. Discover why "clinical death" is not the end of brain activity, why a flat EEG is deceptive, and why the existence of NDE memories proves the brain was never actually "off."

This article serves as the foundational overview for this Near-Death Experiences series

Near-death experiences are often presented as a simple challenge to neuroscience. The claim is straightforward: the brain was not functioning, yet consciousness continued. From this, a larger conclusion is drawn—that something non-physical must be responsible.

That conclusion rests on a medical misunderstanding.

Before asking what near-death experiences mean, we need to be clear about what is actually happening inside the brain when they occur. Once that foundation is in place, the supernatural interpretation no longer looks like the default explanation. It looks like a leap.

Table of Contents

- What Clinical Death Actually Means

- What a Flat EEG Does and Does Not Show

- The Brain Does Not Fail All at Once

- Unconscious Does Not Mean Inactive

- The Timing Problem

- Why Medical Language Gets Misread

- What This Changes

- Key Takeaways

- Bottom Line

- Works Cited

Read the other articles in this Near-Death Experiences series:

What Clinical Death Actually Means

People describing near-death experiences frequently say they were “clinically dead.” The phrase sounds absolute. It isn’t.

In medicine, clinical death refers to the absence of heartbeat and breathing. It does not mean the brain has permanently stopped working. It does not mean neural activity has ceased. It does not mean the person is biologically dead (Laureys et al. 105).

That condition is called brain death, and it is defined by irreversible loss of all brain function, including the brainstem. Near-death experiences are not reported by patients who meet that standard. They are reported by people who recover (Wijdicks 191).

This distinction matters because the brain does not shut down the instant the heart stops. Circulatory failure begins a process. It does not flip a switch (Parnia et al. 210).

More Hatchetman Atheist posts:

What a Flat EEG Does and Does Not Show

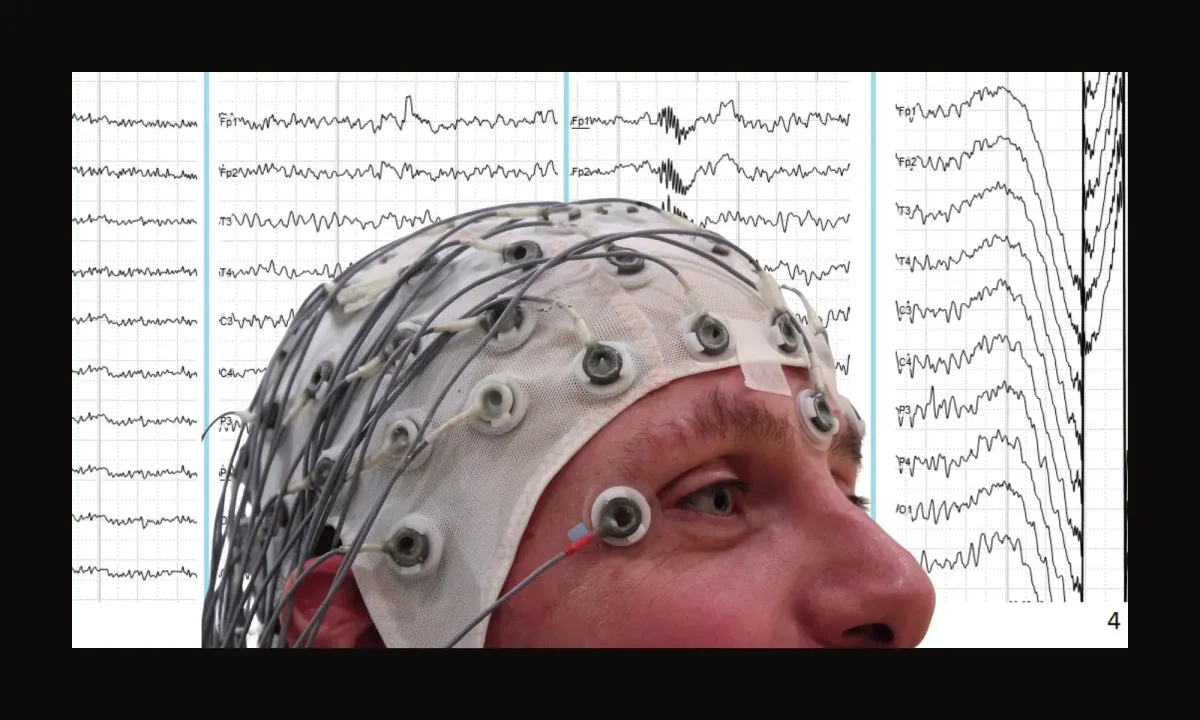

A great deal of near-death literature leans heavily on one phrase: flat EEG. It is often treated as proof that the brain was inactive. That is not what an EEG measures.

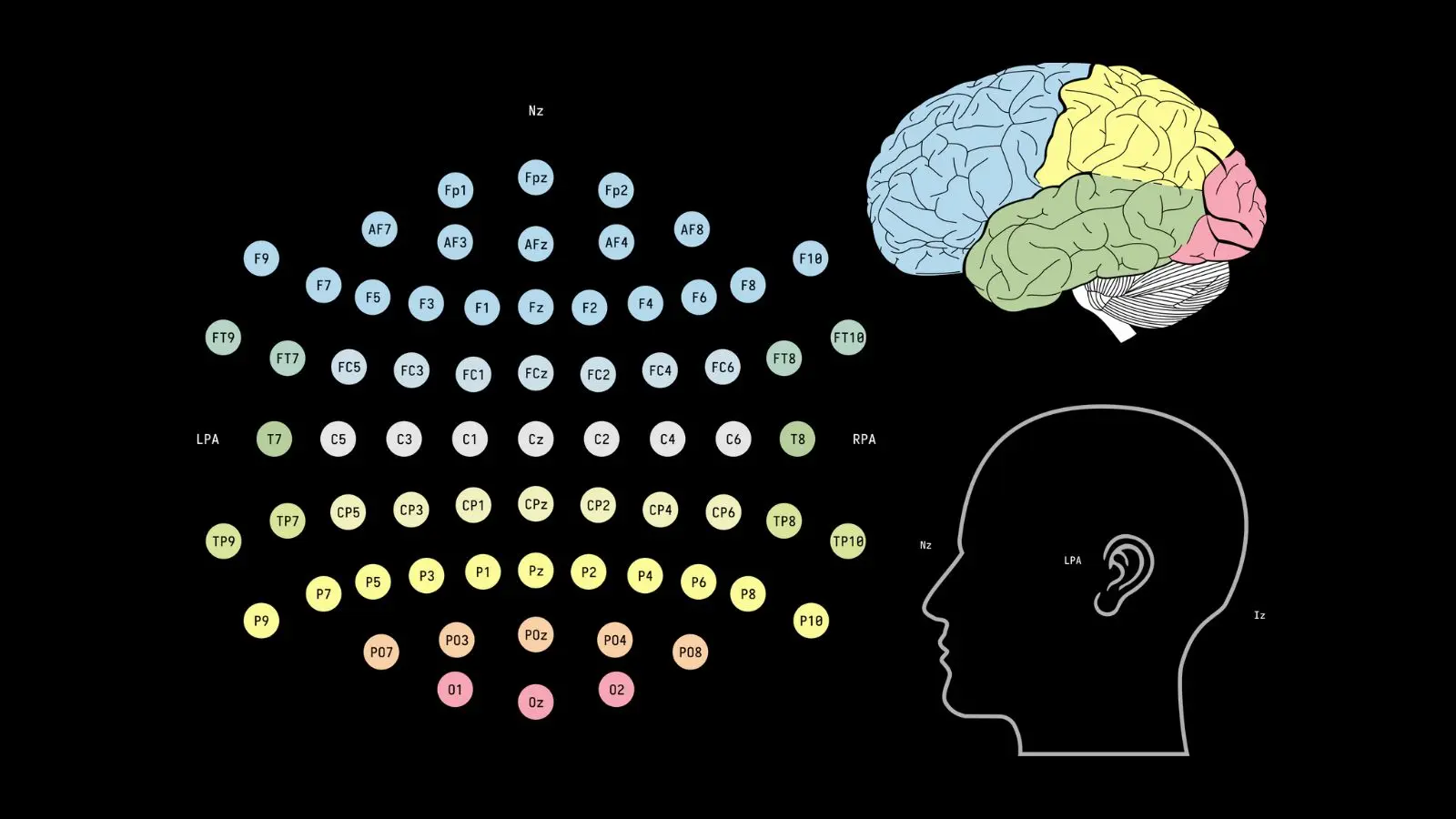

An electroencephalogram records summed electrical activity from neurons near the surface of the cerebral cortex. It is a useful tool, but a limited one (Niedermeyer and Lopes da Silva 3–5).

EEGs do not capture:

• activity in deep brain structures

• brainstem or limbic system function

• brief or localized neural firing

• neurochemical signaling

• low-level activity below detection thresholds (Steriade 137)

A flat EEG means that surface cortical signals have fallen below what the instrument can reliably detect. It does not mean the brain is silent. It does not mean neural processing has stopped. It means the tool has reached its limits (Laureys et al. 106).

No signal detected is not the same thing as no signal present.

EEG electrode placement on the scalp (International 10–20 system), illustrating that EEG records surface cortical activity.

The Brain Does Not Fail All at Once

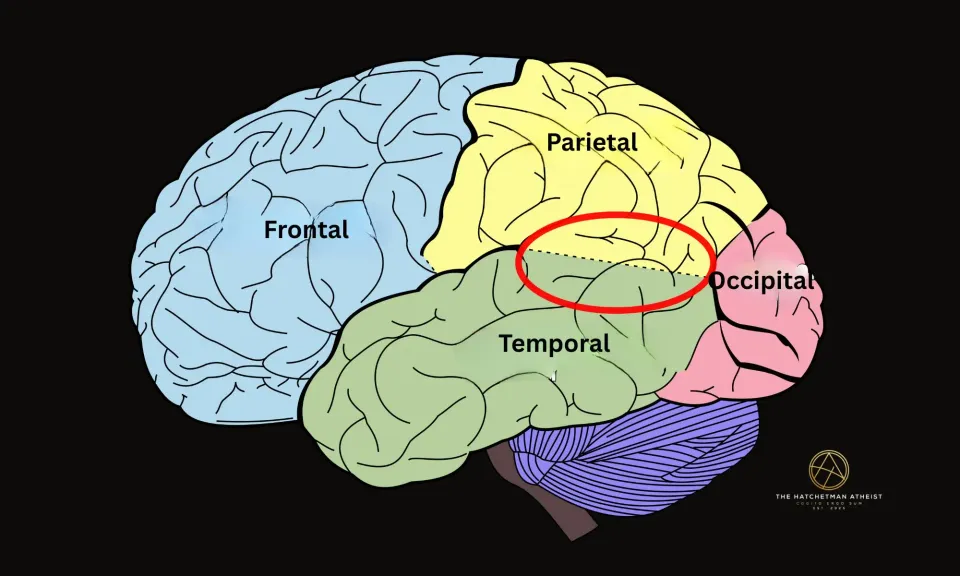

When oxygen delivery to the brain is disrupted, different regions shut down at different speeds. Higher cortical areas are fragile and often fail first. Deeper structures are more resilient.

This matters because the brainstem, midbrain, and limbic system—regions that can remain active longer—are directly involved in:

• bodily awareness

• emotional intensity

• fear and calm responses

• sensory integration (Seth, Suzuki, and Critchley 40)

These are not peripheral systems. They are central to the features people later describe in near-death experiences.

The popular image of a brain that suddenly goes dark is misleading. What actually occurs is an uneven, staggered loss of function across different regions (Parnia et al. 211).

Unconscious Does Not Mean Inactive

Another common assumption is that loss of responsiveness equals loss of experience. It does not.

People under anesthesia, during seizures, or in altered states can appear unconscious and later report vivid experiences. Outward behavior and internal experience are not the same thing (Sanders et al. 558).

Near-death experiences are reported after recovery. They are memories, not live recordings. That introduces a problem that is rarely addressed directly: memory formation requires functioning neural tissue (Zeman 128).

There is no credible evidence that memories can be formed in the absence of brain activity. If an experience is remembered, then some neural systems must have been active when it was encoded.

That fact alone rules out total brain shutdown.

The Timing Problem

Near-death accounts usually assume that the experience occurred at the lowest point of physiological collapse. That assumption is understandable—but unsupported.

What we can say with confidence is only this: the experience was remembered afterward. The brain is capable of generating vivid, coherent experiences:

• as consciousness fades

• during partial impairment

• as awareness returns (Laureys and Maquet 912)

There is no reliable way to timestamp subjective experience to moments of maximum neural suppression. Feeling certain about when something happened is not evidence. It is a judgment made after the fact (Dennett 107).

Until someone can show that a memory was formed during a verified period of global neural inactivity, claims of consciousness without a brain remain speculative.

Why Medical Language Gets Misread

Patients often report being told they were “dead” or “gone.” In clinical settings, those words are frequently used informally to communicate urgency or severity. They are not technical diagnoses (Wijdicks 194).

Such statements do not establish brain death.

They do not establish neural silence.

They do not establish disembodied consciousness.

They establish that the situation was serious—and that the patient survived.

What This Changes

If the brain is not shut down during near-death experiences, then those experiences do not require non-physical explanations by default. The burden of proof shifts.

Once that baseline is accepted, features such as out-of-body sensations, tunnels, lights, peace, and presences stop looking mysterious in principle. They become questions of mechanism.

Those mechanisms will be addressed directly in the posts that follow. They are not speculative. They are reproducible.

Key Takeaways

Heart ≠ Brain

“Clinical death” means the heart stopped, not the brain. Neural activity can persist for minutes after circulation ceases.

EEG Limits

A “flat” EEG does not mean a silent brain. It means surface sensors can no longer detect activity in deeper brain regions that may still be functioning.

The Memory Smoking Gun

Memories cannot form without a working brain. If an NDE is remembered, the brain was—by definition—active during the experience.

Staggered Shutdown

The brain has no single power switch. Higher cognitive functions fail first, while deeper emotional and perceptual systems are often the last to shut down.

Bottom Line

There is no evidence that near-death experiences occur in the absence of brain activity.

A flat EEG does not show a non-functioning brain.

Unconsciousness does not mean absence of experience.

Memory formation alone rules out total neural inactivity.

Near-death experiences can be powerful, vivid, and life-changing—but they do not occur without a working brain.

The default explanation is neurological. Any supernatural interpretation has to argue against that reality, not around it.

If this work has been useful to you, feel free to buy me a coffee.

Works Cited

Dennett, Daniel C. Consciousness Explained. Little, Brown and Company, 1991.

Kirino, T. “Delayed Neuronal Death in the Gerbil Hippocampus Following Ischemia.” Brain Research, vol. 239, no. 1, 1982, pp. 57–69.

Laureys, Steven, et al. “The Neural Correlates of (Un)Awareness: Lessons from the Vegetative State.” Progress in Brain Research, vol. 150, 2005, pp. 105–121.

Laureys, Steven, and Pierre Maquet. “Tracking the Recovery of Consciousness.” Progress in Brain Research, vol. 150, 2005, pp. 907–918.

Niedermeyer, Ernst, and Fernando Lopes da Silva. Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields. 5th ed., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

Parnia, Sam, et al. “AWARE—AWAreness during REsuscitation.” Resuscitation, vol. 85, no. 12, 2014, pp. 1799–1805.

Sanders, Robert D., et al. “Mechanisms of Anesthesia.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 367, no. 19, 2012, pp. 1856–1865.

Seth, Anil K., Kazuyuki Suzuki, and Hugo D. Critchley. “An Interoceptive Predictive Coding Model of Conscious Presence.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 2, 2012, article 395.

Steriade, Mircea. Neuronal Substrates of Sleep and Epilepsy. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Wijdicks, Eelco F. M. Brain Death. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Zeman, Adam. Consciousness: A User’s Guide. Yale University Press, 2002.

Image Credits

Hero image (composite):

Composite image created from the following sources:

- Human EEG artifacts by Andrii Cherninskyi, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 4.0 International.

- EEG cap with electrodes by Chris Hope, via Flickr/Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic.

This composite image has been cropped, resized, and combined from the original works and is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license.

Inline image:

Image source: EEG electrode placement diagram (International 10–10 system), public domain (CC0), via Wikimedia Commons.