Why Didn't the Disciples Recognize Jesus After the Resurrection?

Why the risen Jesus goes unrecognized—Emmaus, garden, and sea scenes—and what that says about the story’s logic.

Table of Contents

- The Great Disappointment: A Crash Course in Letdown Theology

- Déjà Vu in Devotion: Other Faiths That Rewrote the Ending

- Now Enter Jesus, Stage Left

- The Road to Emmaus: Recognition at the Table, Not the Road

- Mary Magdalene in the Garden: Recognition by Voice, Not Sight

- The Miraculous Catch: Meaning Before Identity

- Thomas the Skeptic: Recognition Demands the Body

- Recognition as Testimony, Not Perception

- Conclusion: Faith, Fracture, and the Power of Story

- Scriptural FAQ

- Credits

- Works Cited

Several Gospel narratives describe the disciples failing to recognize Jesus after the resurrection. Rather than treating these scenes as awkward storytelling glitches, this article examines the pattern through psychology, comparative history, and disciplined historical analysis. The question is not whether belief was sincere, but how belief behaves when expectations fracture and meaning must be reconstructed.

The Great Disappointment: A Crash Course in Letdown Theology

Imagine giving away your farm, quitting your job, and putting on your best white robe to watch the sky for Jesus—only for October 22, 1844, to roll by like any other Wednesday. Welcome to the world of the Millerites, a nineteenth-century apocalyptic movement led by William Miller. Convinced that Jesus would return on that date, thousands of followers waited expectantly. Spoiler alert: he did not.

But here is the twist—many did not abandon the belief. Instead, they reinterpreted it. Some claimed Jesus had returned, just not in a way anyone could see. Others argued the date marked a heavenly event invisible to human eyes. Rather than collapsing under the weight of failure, the movement pivoted. From its ashes emerged new religious groups, most notably the Seventh-day Adventists, who reframed disappointment as part of a divine plan cleverly hidden from human perception.¹

The prophecy failed.

The belief survived.

Déjà Vu in Devotion: Other Faiths That Rewrote the Ending

This kind of theological improvisation is not unique. When deeply held expectations collide with reality, people do not always discard the belief. Often, they renovate it.

Take Sabbatai Zevi, a seventeenth-century Jewish messianic claimant. When he was forced to convert to Islam, that should have been the end of the story. Instead, his followers interpreted the conversion itself as a mystical descent necessary for cosmic redemption.

Or consider the Rastafarian reverence for Haile Selassie. When he died in 1975, many adherents rejected the premise of death altogether. Selassie, they argued, had transcended into the spiritual realm. Physical absence did not invalidate divine status; it redefined it.

Then there are the so-called Cargo Cults of Melanesia. Indigenous communities encountered Western military forces whose material abundance appeared inexplicable. When the goods stopped arriving, belief did not evaporate. Instead, ritual systems emerged to explain the interruption and preserve meaning within an existing sacred framework.

In each case, belief did not shatter under the strain of unmet expectations. It bent, adapted, and reorganized itself to preserve coherence.

Now Enter Jesus, Stage Left

That same psychological toolkit applies neatly to the resurrection story.

The execution of Jesus was not just unexpected—it was catastrophic. Whatever Jesus thought of himself, the idea that he anticipated execution followed by bodily resurrection reads suspiciously like a narrative written after the fact. From the standpoint of historical scholarship and method, scholars argue that Jesus likely understood himself as an apocalyptic prophet—perhaps even a forerunner to a messianic figure—but not the climactic redeemer himself.²

When Jesus was arrested, humiliated, and killed, his followers were left with a worldview in pieces. This is precisely the environment in which reinterpretation becomes psychologically necessary.

Belief does not simply vanish.

It looks for a way forward.

The Road to Emmaus: Recognition at the Table, Not the Road

In Luke 24, two disciples are walking the road to Emmaus, a journey of roughly seven miles—a walk that would have taken several hours. They are discussing recent events surrounding Jesus’ death, including reports that his tomb was found empty and claims that he was alive. A stranger joins them along the way. For the duration of this extended walk, they speak openly with him about these developments, puzzling over what they might mean, never suspecting who he is.

Only later, during the shared meal, does recognition occur. At the precise moment they realize who he is, Jesus immediately vanishes. *“Then their eyes were opened, and they recognized him; and he vanished from their sight.”*³

The structure is almost textbook. Recognition is immediately validated by a supernatural act. The miracle does not advance the story so much as punctuate it. Recognition is correct because it is followed by magic.

Mary Magdalene in the Garden: Recognition by Voice, Not Sight

John’s Gospel offers a more intimate variation. Mary Magdalene encounters a man near the empty tomb and assumes he is the gardener. This misidentification persists despite proximity and direct interaction. Visual recognition fails completely.

Only when the man speaks her name does recognition occur. Identity is not established by appearance but by emotional resonance.

The Miraculous Catch: Meaning Before Identity

A third version appears in John 21. The disciples are fishing when a man on the shore offers advice. They follow it, and their nets fill dramatically. Only after this meaningful event does realization dawn: this must be Jesus.

Here, recognition follows outcome rather than observation—an example of post hoc reasoning embedded directly into the narrative.

Meaning comes first.

Recognition follows.

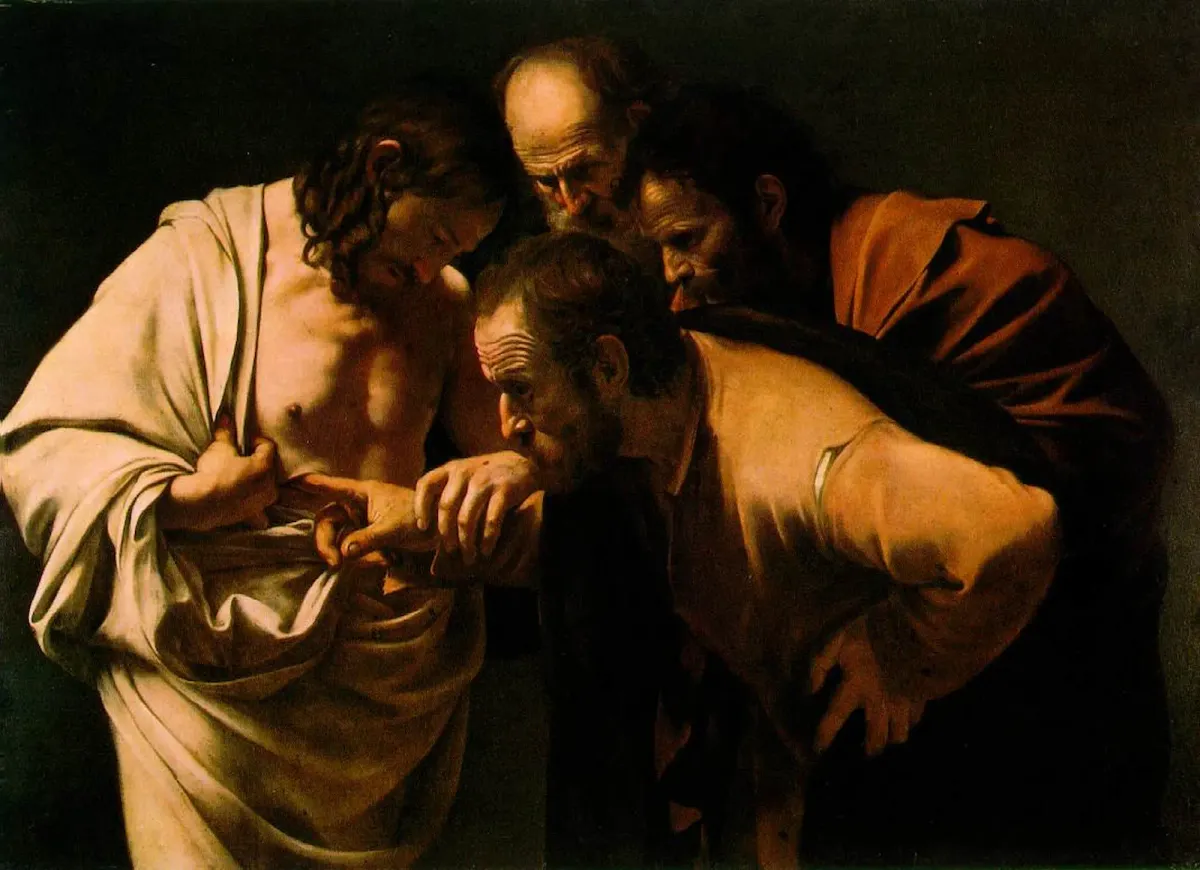

Thomas the Skeptic: Recognition Demands the Body

The Thomas episode belongs with these stories. Unlike the others, Thomas does not fail to recognize Jesus. He refuses to accept recognition without physical verification. He insists on seeing and touching the wounds of crucifixion.

This detail matters. The narrative makes clear that Jesus’ body still bears the marks of execution. Whatever believers mean by “glorified” flesh, it is not a body so transformed that the wounds are gone. The body described is continuous with the one that was crucified.

Recognition as Testimony, Not Perception

Apologetic explanations often claim that Jesus’ resurrected body was altered or that he deliberately concealed his identity. The texts themselves undermine this explanation. The wounds remain.

If the body is continuous, then non-recognition must serve a narrative purpose. Jesus is allowed to remain unknown until recognition is required—and when recognition occurs, it is often confirmed through a supernatural sign.

Taken together, these scenes read less like reports of encounters and more like testimony shaped after the fact.

The Paul material is an easy place for sloppy reasoning, so it’s worth being explicit: pointing out what Paul does not narrate can shade into an argument from silence if it’s treated as decisive proof rather than as one data point in a broader analysis.

Conclusion: Faith, Fracture, and the Power of Story

None of this proves that a resurrection did not occur. What it does show is that the Gospel narratives behave exactly as stories shaped by grief, memory, and belief under pressure tend to behave.

Belief did not collapse.

It adapted.

Scriptural FAQ

- Road to Emmaus: Luke 24:13–35

- Mary Magdalene and the gardener: John 20:11–16

- Miraculous catch of fish: John 21:1–14

- Thomas and the wounds: John 20:24–29

- Resurrection appearances without narrative detail: 1 Corinthians 15:3–8

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so on patreon.

Credits

Caravaggio, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (c. 1601–1602), oil on canvas, Sanssouci Picture Gallery, Potsdam. Public domain. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Works Cited

- Festinger, Leon, Henry W. Riecken, and Stanley Schachter. When Prophecy Fails. Harper & Row, 1956.

- Ehrman, Bart D. How Jesus Became God. HarperOne, 2014.

- The Holy Bible, New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition. National Council of Churches, 2022.

- Vermes, Geza. The Resurrection: History and Myth. Doubleday, 2008.