A Quick Note About Evidence

A skeptic’s guide to weighing evidence: why subjective claims and eyewitness reports mislead, and why only objective, verifiable data deserves belief.

Table of contents

When atheists dismiss the so-called “evidence” presented by religious believers, it’s not an arbitrary act of stubbornness or bias. The real issue is that much of this evidence is, by any reasonable standard, unreliable. Critical thinking means developing the skill to evaluate not just whether evidence exists, but what kind of evidence it is, and how much trust it deserves.

Why subjective evidence fails

Subjective forms of evidence—personal experiences, feelings, visions, even the much-vaunted eyewitness testimony—are well-known for their unreliability (Loftus 23). Courts of law, for instance, don’t hand down convictions based solely on someone’s say-so if more objective, forensic evidence is available. Humans are simply too prone to error, misperception, and, occasionally, outright fabrication (Shermer 47).

Seven realities to keep in view

- The world is home to a vast array of religions, most of which contradict one another on fundamental points of doctrine.

- Devout followers from these different religions often report divine or supernatural experiences—sometimes dramatic, sometimes subtle.

- If any one religion’s doctrine is correct, then the supernatural experiences reported by followers of other religions must be delusional, misunderstood, or fabricated.

- Human beings, being what they are, will inevitably include some outright liars among those claiming religious experiences.

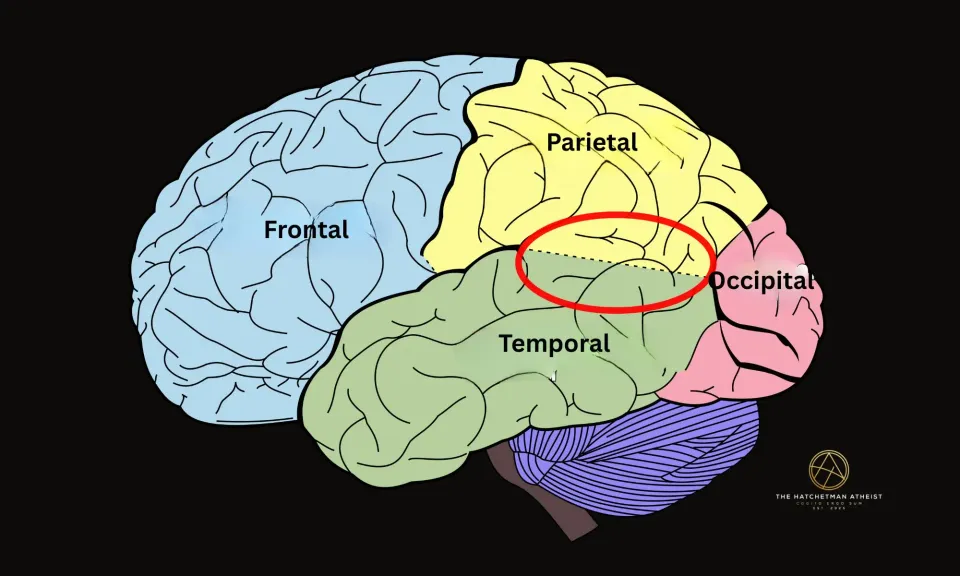

- Many others are honestly mistaken, their “spiritual” moments rooted in psychological, emotional, or physiological causes rather than the supernatural (Shermer 67).

- Even the most sincere individuals cannot reliably distinguish between a genuine supernatural event and a powerful internal experience—the line is blurry, if not invisible (Loftus 51).

- The upshot: even honest, earnest believers are subject to subjective error. Their testimony, no matter how heartfelt, is not objectively reliable evidence.

Two cognitive options

Given these realities, when someone claims to have had a spiritual experience, we’re left with only two basic cognitive options:

- Some of these reported experiences are real encounters with the supernatural, while the rest are either lies or honest mistakes.

- All of these experiences are either lies or honest mistakes.

Practical implications

If we choose option 1, we’re forced to admit that, since at least some claims are false or mistaken, and since there’s no objective way to distinguish the “real” from the “fake,” we cannot rationally accept any particular claim as evidence of the supernatural. Without hard, objective evidence—something verifiable, measurable, and independent of human perception—we have no rational basis for believing any individual report (Loftus 121; Shermer 209).

Option 2 is more intellectually honest and far less messy. Since there is no objective evidence that any supernatural encounter has ever taken place, the rational approach is to treat all such claims as either fraudulent or mistaken, unless and until they are supported by objective evidence.

Critical thinking isn’t just about sniffing out logical fallacies. It’s also about knowing how to weigh the reliability of different kinds of evidence. Without that, the whole project collapses into wishful thinking and confirmation bias (Shermer 21).

New to the night sky? Start with my Astronomy Primer — Moon Phases, Eclipses, and Seasons.

Works Cited

Loftus, Elizabeth F. Eyewitness Testimony. Harvard University Press, 1996.

Shermer, Michael. Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time. Henry Holt, 2002.

New to the night sky? Start with my Astronomy Primer — Moon Phases, Eclipses, and Seasons.

Works Cited

Loftus, Elizabeth F. Eyewitness Testimony. Harvard University Press, 1996.

Shermer, Michael. Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time. Henry Holt, 2002.