The Warehouse, the Mountains, and Paley's Watch

A simple, step-by-step analogy that shows why we instantly spot artifacts in a sea of nature—and why that same split undercuts the classic “watchmaker” move.

...But suppose I had found a watch upon the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place; I should hardly think of the answer which I had before given, that, for any thing I knew, the watch might have always been there. Yet why should not this answer serve for the watch as well as for the stone? why is it not as admissible in the second case, as in the first? For this reason, and for no other, viz. that, when we come to inspect the watch, we perceive (what we could not discover in the stone) that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose…This mechanism being observed (it requires indeed an examination of the instrument, and perhaps some previous knowledge of the subject, to perceive and understand it; but being once, as we have said, observed and understood), the inference, we think, is inevitable, that the watch must have had a maker…

Paley, William. Natural Theology; or, Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, Collected from the Appearances of Nature. (see appendix below for full text)

An answer for Mr. Paley:

Walk into a massive warehouse for a top plumbing manufacturer. Overhead, lights hang in even rows. The polished concrete floor is level and smooth, scored by straight form lines where the pour stopped and started. Thirty-foot shelving runs in long, parallel ranks. Signs label sections by type and size—new-home faucets here, agricultural valves there; pipes grouped by diameter, material, and length. Nothing’s random. It’s all angles, grids, labels, and repeatable patterns.

You don’t need a philosophy class to recognize design. You already know how lights work, what concrete is, how shelving is installed, and what inventory systems do. Human intentions show up as straight lines that stay straight, right angles that stay right, and categories that stay put. The whole scene screams planning, blueprints, and maintenance. You don’t ponder it; your brain sorts it in a heartbeat: artifact, not nature.

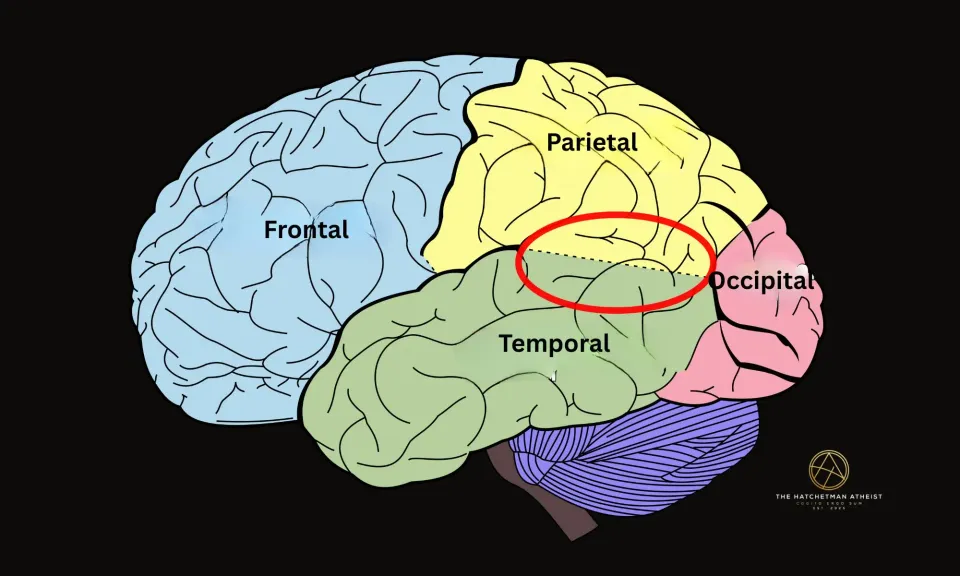

Step outside. The parking lot is flat, striped, and tidy; the planted trees along the curb are the same species, in a neat line, watered by irrigation heads that pop up on schedule. Beyond the property line, the mountain range is jagged and irregular; wild trees arrive in uneven age classes, different species, hit-or-miss health. Granite boulders shoulder out of the ground at odd angles. Instantly, you can tell what’s landscaped and what’s wild.

Now walk into a forest clearing. Dirt. Patchy grass. Bushes and trees scattered without a ruler. A few rough stones half-buried in soil. And there—glinting on the ground—a jeweled Rolex. Your eyes go straight to it. Not to the shrubs, not to the rocks, but to the engineered object with gears, hands, and brand identity. You know what it is, roughly how it works, and who makes it. You don’t confuse it with a pinecone.

Here’s the point. We tell the difference between nature and artifacts because we already carry a working split in our heads—built from experience—between things shaped by wind, water, gravity, and time, and things shaped by tools, standards, and intent. We recognize design by independent clues: straight and parallel lines, standardized parts, category labels, tool marks, manufacturing regularities, and the whole cultural context that surrounds human making.

That’s why the famous watch example doesn’t do the job people think it does¹. We notice the watch because it is not nature. Using that very fact to argue that nature is like the watch is a circle². The prior difference did the work: at most, the watch tells you that artifacts have makers. It does not license the leap from forests and planets to a world-maker. If someone wants to claim that nature itself is designed, they need independent, testable signs of non-human design in nature—signs that beat what we already know natural processes can do³.

So the warehouse helps us see the logic cleanly. Order, repeatable structure, standardized parts, explicit labeling, and contextual traces of manufacturing tell you “artifact” before you even think the word. The mountains remind you what unplanned complexity looks like. And the forest watch shows why your mind separates the categories automatically. That pre-existing split is exactly why the watchmaker move can’t pull nature across the line by analogy. You can’t use the rule that flagged the watch as not nature to argue that nature is like the watch. The difference you started with doesn’t disappear because the argument wants it to.

Notes

- Paley, William. Natural Theology; or, Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity. 1802. Oxford University Press, 2006. Scans: https://archive.org/details/naturaltheologyo00pale

- Hume, David. Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. 1779. Oxford University Press, 1993. Public-domain text: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4583

- Sober, Elliott. Evidence and Evolution: The Logic Behind the Science. Cambridge University Press, 2008. Publisher page: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/evidence-and-evolution/627F53595E37D1E9AC14B4DB16772577

Appendix: William Paley’s “Watchmaker” Passage (1802)

IN crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone, and were asked how the stone came to be there; I might possibly answer, that, for any thing I knew to the contrary, it had lain there for ever: nor would it perhaps be very easy to show the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I had found a watch upon the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place; I should hardly think of the answer which I had before given, that, for any thing I knew, the watch might have always been there. Yet why should not this answer serve for the watch as well as for the stone? why is it not as admissible in the second case, as in the first? For this reason, and for no other, viz. that, when we come to inspect the watch, we perceive (what we could not discover in the stone) that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose, e.g. that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and that motion so regulated as to point out the hour of the day; that, if the different parts had been differently shaped from what they are, of a different size from what they are, or placed after any other manner, or in any other order, than that in which they are placed, either no motion at all would have been carried on in the machine, or none which would have answered the use that is now served by it.

To reckon up a few of the plainest of these parts, and of their offices, all tending to one result:—We see a cylindrical box containing a coiled elastic spring, which, by its endeavour to relax itself, turns round the box. We next observe a flexible chain (artificially wrought for the sake of flexure), communicating the action of the spring from the box to the fusee. We then find a series of wheels, the teeth of which catch in, and apply to, each other, conducting the motion from the fusee to the balance, and from the balance to the pointer; and at the same time, by the size and shape of those wheels, so regulating that motion, as to terminate in causing an index, by an equable and measured progression, to pass over a given space in a given time. We take notice that the wheels are made of brass in order to keep them from rust; the springs of steel, no other metal being so elastic; that over the face of the watch there is placed a glass, a material employed in no other part of the work, but in the room of which, if there had been any other than a transparent substance, the hour could not be seen without opening the case.

This mechanism being observed (it requires indeed an examination of the instrument, and perhaps some previous knowledge of the subject, to perceive and understand it; but being once, as we have said, observed and understood), the inference, we think, is inevitable, that the watch must have had a maker: that there must have existed, at some time, and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers who formed it for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use.

Nor would it, I apprehend, weaken the conclusion, that we had never seen a watch made; that we had never known an artist capable of making one; that we were altogether incapable of executing such a piece of workmanship ourselves, or of understanding in what manner it was performed; all this being no more than what is true of some exquisite remains of ancient art, of some lost arts, and, to the generality of mankind, of the more curious productions of modern manufacture.

Neither, secondly, would it invalidate our conclusion, that the watch sometimes went wrong, or that it seldom went exactly right. The purpose of the machinery, the design, and the designer, might be evident, in whatever way we accounted for the irregularity of the movement, or whether we could account for it or not. It is not necessary that a machine be perfect, in order to show with what design it was made: still less necessary, where the only question is, whether it were made with any design at all.

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so on patreon.

Paley, William. Natural Theology; or, Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, Collected from the Appearances of Nature. Philadelphia: John Morgan, 1802. Internet Archive. Accessed 20 Aug. 2025.

https://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=A142&pageseq=1&viewtype=text