The Shroud of Turin Skeptic’s Encyclopedia: Everything the Apologists Don't Want You to Know

Is the Shroud of Turin a miracle or a medieval forgery? This 2026 update uses the latest science to debunk "resurrection energy" and reweave myths. Explore radiocarbon dating, image chemistry, and historical evidence proving this famous relic is a 14th-century artifact.

Note to Readers:

An annotated reference index is available at the end of this encyclopedia, after the Works Cited list.

The index includes precise page, paragraph, and line references to the Karapanagiotis (2025) PDF and links directly to the external Lexicon Page containing detailed cross-references.

Preface

This encyclopedia is an unapologetically skeptical deep dive into one of the most over-mythologized objects in Western religious culture: the Shroud of Turin. Believers have woven a tapestry of extraordinary claims around this linen, but extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence—and when subjected to rigorous scientific scrutiny, the shroud stubbornly behaves like what it is: a medieval artifact cloaked in medieval imagination.

This work compiles the scientific, historical, chemical, statistical, and physical research available, including the 2025 open-access review by Ioannis Karapanagiotis. It brings together radiocarbon dating results, textile analyses, microscopic studies, image-formation chemistry, historical sourcing, and the thorough dismantling of fringe hypotheses that cling to the shroud like incense residue to cathedral stone.

This encyclopedia is for the curious, the skeptical, the academically minded, and anyone weary of apologetic theatrics masquerading as empirical inquiry.

Belief needs no linen.

Pseudoscience, however, demands confrontation.

Table of Contents

I. Preface

• Preface

Table of Contents

I. Preface & Introduction

• Preface

• Introduction

II. The Science of Dating the Shroud

- Radiocarbon Dating: What It Actually Proved

- Statistical Heterogeneity & Why It Doesn’t Rescue the Shroud

- Radiocarbon Pretreatment: Why Contamination Fails

- Why Radiocarbon Works Everywhere

III. Contamination Claims and Their Demise

- Fire Contamination (Kouznetsov et al.)

- Biological Contamination & “Bioplastic Coatings”

- Chemical Contamination: Vanillin, Lignin, Wishful Thinking

- Sample Fraud & Substitution

IV. The Invisible Reweave Hypothesis

- Claims of a Post-Medieval Repair

- Textile Evidence For and Against

- FTIR & Microscopy Debates

- Why a 16th-Century Patch Cannot Yield a 13th-Century Radiocarbon Date

V. Image Formation: What We Know & What We Don’t

- What STURP Actually Found

- McCrone’s Pigment Hypothesis

- Image Chemistry: Oxidation & Cellulose Degradation

- The Photographic Negative Myth

- The VP-8 Analyzer & the 3-D Myth

- Experimental Image-Formation Techniques

- Why “Not Painted” Does Not Mean “Ancient”

VI. Physics Abuse: Neutrons, Radiation & Resurrection Energy

- The Neutron-Burst Hypothesis

- Why C-14 Conversion Would Destroy the Linen

- When Apologists Move the Goalposts Into the Supernatural

VII. Historical & Artistic Claims

VIII. Pollen, DNA, Dust & Geographic Claims

IX. Geometry, Body Mapping & Forensic Problems

- Why the Shroud Is Not a 360° Body Image

- Anatomical Inconsistencies

- Forensic Disagreements

- Geometry Suggests Artistic Creation

X. Grand Scorecard

XI. Works Cited (MLA)

XII. Reference Index

II. The Science of Dating the Shroud

Radiocarbon dating is the foundation of the modern scientific case for a medieval Shroud of Turin. The testing performed in 1988 by laboratories at Oxford, Arizona, and Zurich remains one of the most thoroughly scrutinized radiocarbon studies ever conducted. Apologists have attempted—persistently but unsuccessfully—to undermine its conclusions through appeals to contamination, statistical anomalies, hypothetical repairs, or exotic physics. None of these efforts overturn the clear result.

The Shroud dates to the medieval period.

The objections collapse under inspection.

1. Radiocarbon Dating: What It Actually Proved

The 1988 radiocarbon tests measured the ratio of C-14 to C-12 isotopes in the linen fibers. The laboratories produced a calibrated age range of 1260–1390 CE, aligning almost perfectly with the Shroud’s historical debut in Lirey, France, in the mid-1300s.

Key points:

- Three independent labs received blind samples.

- All laboratories used rigorous pretreatment protocols to remove contaminants.

- The results were statistically consistent across labs.

- No laboratory reported anomalies indicative of modern or ancient interference.

The Karapanagiotis review affirms that radiocarbon dating remains the only method capable of producing an absolute age determination for the shroud, and no scientific evidence contradicts the medieval date.

2. Statistical Heterogeneity and Why It Doesn’t Rescue the Shroud

Apologists frequently claim the data show “heterogeneity” implying that the sample region cannot represent the whole cloth. However:

- The variation among measurements fell within acceptable statistical limits.

- The inter-laboratory agreement was high.

- No subgroup of data points pushed the date outside the medieval period.

- Even the widest readings still centered in the 13th–14th century range.

- Statistical tests run since 1988 confirm no hidden ancient signal.

Karapanagiotis emphasizes that heterogeneity claims misunderstand the nature of Bayesian calibration curves and the role of sample-weighting in radiocarbon analysis.

In short: variation existed, but variation fully consistent with a single medieval origin.

3. Radiocarbon Pretreatment: Why Contamination Fails

Radiocarbon pretreatment is specifically designed to remove contaminants through:

- ABA (acid–base–acid) chemical cleaning

- Solvent extraction

- Burning to CO₂ and isolation of carbon content

Apologists often insist that contaminants such as oils, sweat, microbes, fire soot, or bioplastic films altered the linen’s age. This fails for multiple reasons:

- Contaminants would need to replace 60–70 percent of the linen’s carbon to shift the date by 1,300 years.

- No known contaminant exists in such quantity in the tested fibers.

- Removal protocols effectively strip surface and embedded organics.

- The labs would have detected a mass discrepancy if contamination were present at required levels.

- No imaging or chemical study has demonstrated contamination even remotely sufficient.

Karapanagiotis notes that ABA cleaning eliminates the hypothesized bioplastic polymers that Rogers and others proposed. The contamination theory collapses under quantitative analysis.

4. Why Radiocarbon Works Everywhere (Even When Apologists Dislike the Result)

Radiocarbon dating is used on:

- Textiles

- Parchments

- Wood

- Plant fibers

- Charcoal

- Bone collagen

- Artefacts from Egypt, Qumran, China, Mesoamerica, Europe, and beyond

It works because:

- C-14 decay follows a predictable exponential curve.

- Contamination profiles are well understood.

- Calibration curves are continually updated.

- Cross-validation with dendrochronology and other chronometers confirms accuracy.

If radiocarbon dating were systematically unreliable, the entire discipline of archaeology would collapse. Instead, it is one of the most robust tools available.

The Shroud is not a special exception.

Its medieval date is not an anomaly.

It is what the data support.

III. Contamination Claims and Their Demise

Every attempt to overturn the radiocarbon date relies on one of four strategies:

- Fire contamination

- Biological contamination

- Chemical contamination

- Sample-switching or fraud

None withstand chemical, statistical, or physical analysis.

Karapanagiotis reviews each claim and shows why they fail.

1. Fire Contamination (Kouznetsov et al.): The Experiment That Failed Reality

In 1996, Kouznetsov, Ivanov, and Veletsky published a paper arguing that the 1532 chamber fire in Chambéry altered the Shroud’s radiocarbon age by injecting combustion products that “relabelled” the linen’s cellulose, making medieval cloth appear medieval but much older originally.

Problems with this claim:

- The experimental conditions were fabricated. Later investigators discovered that the temperatures claimed were physically impossible given the documented fire.

- No lab has ever replicated their results. Multiple independent attempts produced no measurable radiocarbon shift.

- The chemistry was wrong. The proposed reaction mechanism—mass carboxylation of cellulose OH groups—cannot occur at the temperatures of the 1532 event.

- The authors’ credibility collapsed. Their methodology showed irregularities, including unexplained mass changes and inconsistent thermal profiles.

- Karapanagiotis explicitly rejects this mechanism as unsupported, hypothetical, and incompatible with cellulose behavior.

To alter the radiocarbon date by 13 centuries, over 60 percent of the carbon in the sample would need to be replaced. No fire can do this without turning linen to ash.

The fire-contamination hypothesis is dead. It stays dead.

2. Biological Contamination & the “Bioplastic Coating” Myth

Some apologists propose that bacteria or fungi produced a polymeric film (“bioplastic coating”) on the linen that skewed the radiocarbon results.

Scientific problems with this claim:

- The amount required is absurd. A bioplastic layer would need to equal or exceed the mass of the linen itself—never observed.

- Radiocarbon pretreatment removes microbial films through solvent extraction and acid–base cycles.

- Microscopy reveals no thick polymeric layer on the test samples.

- No peer-reviewed study has shown microbial mass-loading sufficient to shift radiocarbon ages by even a few centuries.

- Rogers himself—who once supported this idea—later conceded there was no such coating in the radiocarbon sample.

Karapanagiotis reports zero evidence of bioplastic contamination in any reliable study.

3. Chemical Contamination: Vanillin, Lignin & Wishful Thinking

A popular argument claims that lignin oxidation and vanillin loss imply a first-century age. This is scientifically baseless:

- Vanillin loss is not a clock. Lignin decay rate varies dramatically across environments.

- The shroud has an unknown thermal and chemical history, invalidating any vanillin-based dating attempt.

- Rogers’ argument relied on an unverified assumption that the tested fibers were original warp threads—later shown false.

- Karapanagiotis demonstrates that vanillin analysis cannot produce chronological information and that lignin distribution is irrelevant to radiocarbon dating.

If vanillin were a reliable dating tool, archaeologists would use it.

They do not.

4. Sample Fraud & Substitution Theories (The Last Refuge)

Some believers claim the radiocarbon sample was swapped, contaminated deliberately, or otherwise tampered with.

This requires:

- Collusion among three labs

- Collusion among Vatican custodians

- Collusion among British Museum statisticians

- Perfect execution of a nonexistent forgery scheme

- No whistleblowers

- No documented anomalies

- A swapped cloth that just happens to date precisely to the century the Shroud first appears in history

Every fraud scenario collapses under its own weight.

Karapanagiotis notes that all sampling, documentation, and chain-of-custody records are intact, with no evidence of deception. The suggestion of collusion is conspiracy thinking, not scholarship.

IV. The Invisible Reweave Hypothesis

The “invisible reweave” is the last refuge of those who accept that contamination cannot save the radiocarbon date but refuse the medieval conclusion. It proposes that the C-14 sample came from a later repair so skillful that no one noticed until modern apologists needed it.

No textile expert, peer-reviewed paper, or laboratory analysis has ever confirmed such a repair.

1. Claims of a Post-Medieval Repair

Proponents suggest that after the 1532 fire, artisans rewove charred sections using newly spun threads. The theory requires:

- A perfect repair undetectable by

– microscopy

– UV fluorescence

– transmitted light

– microchemical analysis - And that this repair happened precisely where the C-14 sample was taken.

- And that the repair threads had a radiocarbon age matching exactly 1260–1390 CE.

- And that all three labs received only repaired fibers, not original ones.

Historical records mention no such repair, and medieval reweaving techniques could not produce undetectable splices.

Karapanagiotis includes the claim but gives no support: the hypothesis remains speculative and unsubstantiated.

2. Textile Evidence For and Against

Proponents claim:

- Cotton mixed with flax indicates patching.

- Thread splices show reinserted segments.

- Color variation suggests mendwork.

- Dye or mordant residues could indicate touching-up.

But specialists in ancient textiles reject these interpretations:

- Cotton and flax cross-contamination is common in medieval weaving rooms.

- The Shroud shows no structural splice lines under high-resolution imaging.

- UV photography—excellent at exposing repairs—reveals no patch geometry.

- No textile conservator has ever endorsed the hypothesis.

Flury-Lemberg, one of the world’s foremost textile conservators, found no evidence whatsoever of reweaving during the 2002 restoration.

3. FTIR, Microscopy & Corner-Sample Chemistry

Some researchers, including Rogers, reported that fibers from the radiocarbon corner differed chemically from fibers taken elsewhere. These differences included:

- FTIR spectral variation

- Presence of cotton interspersed with flax

- Starch or gum coatings

- Slightly different fluorescence

The problem is simple:

Surface chemistry ≠ structural repair.

Reasons these observations do not imply reweaving:

- Contact, folding, soot, humidity, and adhesives can alter surface chemistry.

- Cotton appears in many parts of the Shroud, not only the C-14 corner.

- Starch residues exist across the cloth, consistent with medieval sizing.

- No imaging method shows fiber replacement or spliced threads.

Karapanagiotis notes such differences but emphasizes they do not overturn the radiocarbon result.

4. Why a 16th-Century Patch Cannot Yield a 13th-Century Radiocarbon Date

Even if the C-14 corner were partially repaired, the radiocarbon results would show mixed ages. Instead, all three labs obtained dates tightly clustered between 1260 and 1390 CE.

This means the following would need to be true:

- The patch threads were not 16th century

- The patch threads somehow radiocarbon-dated to the exact century when the Shroud first appears in European records

- All subsamples—cut from different parts of the same area—would have to have

– the same contamination ratio

– the same effective radiocarbon age

– the same pretreatment behavior - And this perfect tuning would need to happen by accident

Radiocarbon math is unforgiving:

If you mix younger and older fibers, the mean age must fall between them.

The Shroud’s date does not fall between antiquity and the 1500s—it falls squarely in the 13th–14th centuries.

The reweave hypothesis requires miracles to work. Science does not.

Verdict for the Invisible Reweave Hypothesis

- Undertermined only in the trivial sense that no one can prove no thread was ever repaired.

- Debunked in every meaningful scientific sense.

- Unsupported by microscopy, spectroscopy, textile analysis, or historical records.

- Statistically incompatible with the radiocarbon clustering.

- Rejected by textile professionals.

The “invisible reweave” solves no problems.

It only creates new ones.

V. Image Formation: What We Know and What We Don’t

The image on the Shroud is the primary magnet for speculation. Apologists insist its formation is inexplicable. Scientists disagree. The image can be explained as the chemical alteration of linen cellulose—no pigments, no supernatural events, no divine photography required.

Karapanagiotis summarizes the physical and chemical findings clearly: the image is a product of surface oxidation and dehydration of the linen fibrils. Nothing about the phenomenon requires a mechanism outside known physics or medieval technology.

1. What STURP Actually Found

STURP (the 1978 Shroud of Turin Research Project) examined the linen using microscopy, spectroscopy, reflectance studies, and chemical analysis. Their findings are routinely misquoted by believers, so they must be stated precisely.

STURP concluded:

- No pigment, dye, paint, or stain forms the body image.

- The coloration is confined to the outermost fibrils—only microns deep.

- The mechanism is consistent with oxidation, dehydration, and conjugation of cellulose.

- The image does not penetrate through the cloth.

- The image can be simulated through chemical and thermal processes.

What this does not mean:

- It does not mean the image is miraculous.

- It does not mean photography existed in antiquity.

- It does not mean the image is anatomically accurate.

It simply means the image is not pigment-based. Medieval artisans did not always use pigment to create devotional images. Heat, chemicals, and surface reactions were known.

2. McCrone’s Pigment Hypothesis

Walter McCrone, a renowned microscopist, argued that the image contained red ochre and vermilion. STURP reanalyzed his samples and found:

- Iron oxide particles were present but did not correlate with image density.

- Vermilion appeared only in bloodstain areas, not in the body-image regions.

- No binding medium consistent with painting was detected.

The scientific consensus rejects McCrone’s interpretation because:

- The distribution of particles is random.

- The density is insufficient to form a visible image.

- Environmental contamination explains their presence.

Karapanagiotis affirms the consensus: the image is not formed by pigments. McCrone was wrong, but his work helped clarify the chemical profile.

3. Image Chemistry: Oxidation, Dehydration, and Surface Degradation

The Shroud image is a form of surface degradation. Chemical studies show:

- Oxidation of cellulose

- Dehydration of the top fibrils

- Conjugated carbonyl groups contributing to color

- No alteration below the fibril surface

These findings match several naturalistic processes, including:

- Mild thermal exposure

- Low-temperature chemical reactions

- Acidic vapors from decomposition

- Contact-transfer from bas-relief molds

- Long-term light exposure

Karapanagiotis notes the image is chemically shallow and structurally consistent with surface-bound oxidation—nothing remotely supernatural.

4. The Photographic Negative Myth

Believers frequently claim the Shroud is a perfect photographic negative. It is not:

- A true photographic negative preserves tonal values systematically.

- The Shroud’s image shows uneven shading dictated by cloth-to-body distance or cloth-to-object contact.

- Many medieval techniques can create negative-like images, such as rubbings or bas-relief contact transfers.

The shroud’s negative appearance is an artifact of tonal inversion, not photography.

Photography did not exist in antiquity.

But tone inversion did—and was exploited in devotional art.

5. The VP-8 Analyzer and the 3-D Information Myth

The VP-8 Image Analyzer transforms brightness into height to produce topographic relief. When applied to the Shroud, it generates a pseudo-3D image.

Apologists insist this proves:

- the image encodes real 3D information

- the Shroud captured actual body geometry

- the image cannot be artificial

All these claims fail:

- Any image with monotonic shading can produce pseudo-3D outputs.

- Coins, paintings, drawings, and relief images produce similar VP-8 results.

- The Shroud actually fails several 3D tests—for example, facial flattening and hair geometry discrepancies.

Karapanagiotis states that while the intensity-distance correlation is interesting, it does not imply miraculous origin.

The 3D effect reflects the simplicity of the image, not its authenticity.

6. Experimental Image-Formation Techniques

Multiple researchers have produced Shroud-like images using:

- Bas-relief contact

- Thermal imprints

- Acidic vapor reactions

- Powder rubbings

- UV-activated oxidation

- Chemical dehydration techniques

These reproductions match several key properties:

- Superficiality

- Monotone coloration

- Negative-like appearance

- 3D-effect in VP-8

- Lack of pigment penetration

No single method reproduces every characteristic perfectly, but many reproduce most. Image formation is not a mystery. It is a chemistry problem, not divine optics.

7. Why “Not Painted” Does Not Mean “Ancient”

Believers argue that because the Shroud is not painted, it must be authentic. This commits a false dilemma.

Medieval artisans:

- used heat to produce scorch-like images

- exploited surface chemical reactions

- transferred images using cloth molds

- created negative-tone devotional icons

- manipulated linen through controlled exposure

The absence of paint does not imply antiquity; it implies technique.

Authenticity does not follow from lack of pigment.

Artistry does.

VI. Physics Abuse: Neutrons, Radiation and Resurrection Energy™

When all chemical, textile, microscopic, and historical objections fail, apologists often flee into the glittering refuge of speculative physics. Neutron bursts, gamma-ray flares, quantum tunneling, and unspecified “resurrection energies” get invoked like theological fireworks. These claims share a single quality: none survive contact with actual physics.

Karapanagiotis reviews such ideas with academic restraint. Here, we examine their scientific impossibility directly.

1. The Neutron-Burst Hypothesis

The theory proposes that at the moment of resurrection, a supernatural burst of neutrons altered the linen’s carbon isotopes, making a 1st-century cloth appear medieval.

In nuclear reactors, neutrons can convert carbon isotopes. But the dose required to shift the Shroud’s radiocarbon age by more than a millennium would cause catastrophic damage. Linen would not survive the neutron bombardment needed to affect C-14 ratios measurably.

Physical consequences ignored by apologists:

- neutron capture generates gamma emission

- cellulose undergoes fragmentation under irradiation

- the cloth would show deep lattice damage

- neutron activation products would be detectable

None appear on the Shroud.

Karapanagiotis notes that the neutron-flux mechanism lacks empirical grounding and is usually paired with supernatural claims—placing it outside the scientific domain entirely.

2. Why C-14 Conversion Would Destroy the Linen

To alter radiocarbon ratios enough to shift a date from the 1st century to the 13th, the cloth would require a neutron fluence so intense that:

- the fibers would char, weaken, or disintegrate

- the cellulose chains would undergo radical scission

- volatile organics would be liberated

- spectral signatures of irradiation would appear

None of these effects are present.

Studies of neutron-irradiated cellulose confirm that organic fibers degrade rapidly when exposed to such flux. Linen that endured this level of neutron exposure would resemble scorched powder, not an intact relic.

3. When Apologists Move the Goalposts into Supernatural Physics

These arguments follow a predictable pattern:

- invoke real physics

- encounter contradictions

- abandon physics for supernatural exemption

For example:

- neutrons alter C-14 → correct

- required neutron flux destroys linen → correct

- therefore Jesus emitted special neutrons that changed isotopes without damaging the cloth → not physics

Once an argument requires radiation that selectively alters carbon isotopes while avoiding every other consequence of radiation, it ceases to be scientific. A miracle may be a theological explanation, but it is not a physical one.

Karapanagiotis acknowledges that proposed neutron sources are often explicitly supernatural, which removes them from the empirical arena entirely.

VII. Historical and Artistic Claims

Attempts to anchor the Shroud of Turin in antiquity often depend not on firm evidence but on interpretive enthusiasm. Medieval illustrations are treated as coded eyewitness testimony, relic inventories as unbroken provenance, and artistic similarities as secret fingerprints of authenticity. When examined critically, these claims unravel quickly.

This section reviews three major historical arguments: the Pray Codex, supposed Constantinopolitan lineages, and iconographic parallels. None withstand scrutiny.

1. The Pray Codex

The Pray Manuscript (c. 1192–1195) is a Hungarian illuminated text sometimes claimed to depict the Shroud of Turin. Apologists point to features they believe correspond to the Shroud’s burn holes, posture, and winding cloth. Yet none of these align with what the Codex actually represents.

Key problems:

- The decorative marks interpreted as “poker holes” are typical medieval motifs, appearing widely in manuscript ornamentation. They are not burn patterns.

- The crossed-hand posture is a standard iconographic convention used in medieval depictions of Christ, not a forensic detail.

- The scene in question portrays the Resurrection, not a burial wrapping.

- The illustrated cloth is patterned; the Turin Shroud is not.

Outside apologetic literature, no medieval art historian identifies the Pray Codex as depicting the Turin Shroud. The resemblance is superficial and entirely explicable within medieval artistic norms.

2. Constantinople’s Cloth Traditions

Some argue that the Shroud of Turin is identical to various burial cloths once kept in Byzantium. The logic typically hinges on associations, not descriptions: if Constantinople possessed relics of Christ, and the Shroud is a relic of Christ, then perhaps they are the same object.

Why the claim fails:

- Byzantium housed many cloth relics: mandylions, sweat cloths, face cloths, and multiple burial linens. None match the Shroud’s size or imagery.

- Descriptions consistently refer to face-only images or small-format cloths used as icons.

- No Byzantine inventory describes a 4.4 × 1.1 m full-body linen with faint tonal imagery.

- There is no documented chain of custody connecting any Byzantine cloth to the Shroud’s first historical appearance in Lirey, France, in the mid-14th century.

Karapanagiotis notes that the radiocarbon result aligns precisely with this documented medieval debut—something no Byzantine lineage can reconcile.

3. Iconographic Parallels

Another argument claims that similarities between medieval depictions of Christ and the Shroud mean the Shroud must predate the iconography. This reverses the direction of influence.

Consider:

- By the 12th to 14th centuries, Christ’s facial type was standardized: long hair, forked beard, solemn expression. The Shroud’s face reflects this convention.

- Artistic conventions often produce characteristics that appear “shroud-like”: elongated figures, stabilized postures, symbolic wounds, and simplified anatomy.

- Artists influenced each other. A medieval artisan producing a devotional cloth would naturally conform to familiar religious imagery.

No iconographic scholar cites pre-1350 artworks as evidence of the Shroud’s existence. The similarities are cultural echoes, not historical fingerprints.

VIII. Pollen, DNA, Dust, and Geographic Claims

When historical arguments collapse and radiocarbon dating refuses to budge, apologists often retreat into the microscopic world, hoping pollen grains, genetic fragments, or stray particles will reveal a hidden ancient biography for the Shroud. But surface debris is not a time capsule. It is a record of exposure, handling, contamination, and centuries of movement. Scientific analysis—including the work summarized by Karapanagiotis—demonstrates that none of these materials support a 1st-century origin.

1. Pollen Studies: What They Really Show

Pollen is often invoked as the shroud’s botanical passport, supposedly proving a journey from Jerusalem to Europe. The case rests heavily on Max Frei’s adhesive-tape samples, which have long been criticized for methodological weaknesses.

Key issues:

- Frei’s sampling was uncontrolled and failed to follow modern contamination protocols.

- Several of the identified pollen types were misclassified or are widespread across Europe.

- Later analyses failed to confirm any Middle Eastern pollen assemblage.

- The shroud has been displayed, carried, handled, and stored in environments full of airborne pollen.

Karapanagiotis notes that such microscopic findings cannot determine provenance or age. The presence of pollen merely reflects exposure to the world, not origin in a particular region.

2. DNA: A Record of Handling, Not Antiquity

A 2015 DNA survey of the shroud detected a medley of human, plant, fungal, and bacterial DNA from multiple continents. Believers sometimes highlight Middle Eastern haplogroups as evidence of ancient authenticity, but this interpretation ignores how DNA actually accumulates.

Consider:

- Human DNA appears whenever people touch, breathe near, or shed cells onto an object.

- Plant DNA reflects environmental exposure, including chapels, storage boxes, and open-air displays.

- The shroud has traveled through France and Italy, been touched by clergy and pilgrims, and undergone repairs.

- DNA contamination is unavoidable and constant.

As Karapanagiotis states, the DNA findings do not contradict the medieval radiocarbon date because they do not provide chronological information at all.

3. Metal Particles and Miscellaneous Dust

Some claim that trace metals—such as electrum particles or iron oxide—indicate Byzantine or Near Eastern origins. These interpretations rely on reading intention into materials that are far more mundane.

Points to consider:

- Electrum dust is common in medieval liturgical environments, reliquaries, and gilded decorations.

- Iron oxide is ubiquitous and was shown by STURP to be randomly distributed, not correlated with the image.

- Dust lacks archaeological context on an object that has moved widely and been repeatedly exposed.

Microscopic debris merely reveals that the cloth has lived a long, heavily handled life—nothing more.

IX. Geometry, Body Mapping, and Forensic Problems

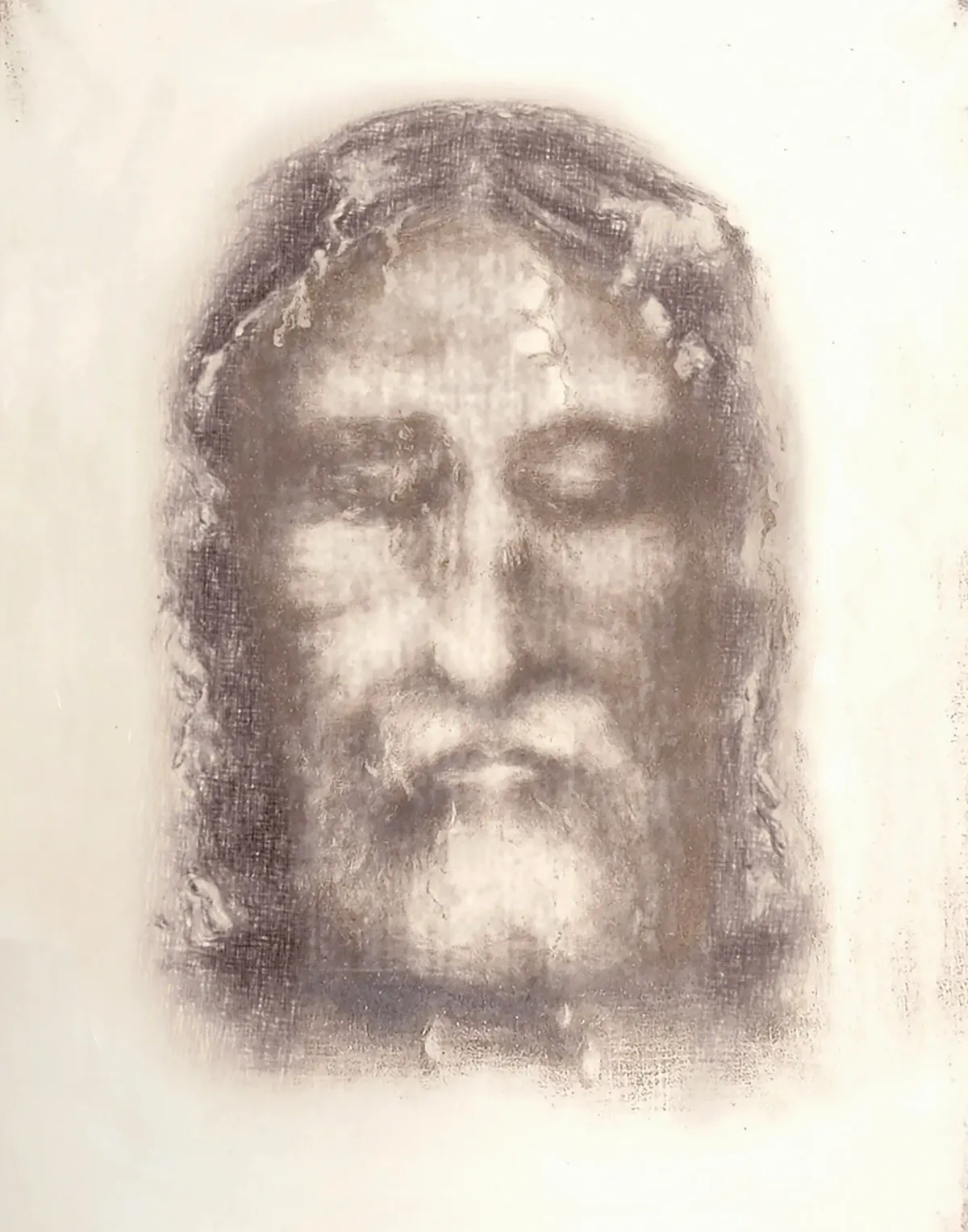

If the Shroud of Turin truly wrapped a real corpse, its image should reflect real-world three-dimensional anatomy and expected distortions from draping fabric over a body. Instead, the shroud presents a pair of flat, front-and-back projections that obey artistic logic rather than physical behavior. The geometric and anatomical mismatches undermine claims of authenticity.

1. Why the Shroud Is Not a 360° Body Image

A cloth wrapped around a human form should display continuous contact impressions along the sides of the head, torso, arms, and legs. The shroud displays none of these.

Observations:

- Only frontal and dorsal images exist; the sides are blank.

- A wrapped cloth would produce lateral flattening, compression, and distortion of features; none appear here.

- The face shows symmetrical, undistorted proportions inconsistent with draping around a skull.

- Hair falls straight downward as if on a vertical plane, not outward or sideways as gravity would dictate for a reclining body.

- The distance-intensity gradients, often touted as “3D encoding,” are consistent with bas-relief contact processes, not suspended imaging.

These geometric properties indicate a planar image-formation mechanism rather than burial wrapping.

2. Anatomical Inconsistencies

If the image represented an actual crucified corpse, its proportions and wound behavior should match expected physiology. Instead, multiple inconsistencies suggest artistic stylization.

Key discrepancies:

- The head is proportionally too small for the body.

- The arms appear unnaturally long and extend downward as if lengthened to achieve the hand-crossing pose.

- The fingers appear elongated beyond anatomical norms.

- The legs are perfectly straight and parallel, contrary to normal rigor mortis positioning.

- The neck is absent, with the head appearing to rest directly on the torso, a common medieval motif.

- Overall symmetry and body positioning match artistic convention, not forensic realism.

These features point to representational art rather than anatomical documentation.

3. Forensic Disagreements and What They Actually Mean

Forensic specialists do not agree on what the shroud depicts, and their disagreements reveal ambiguity rather than authenticity.

Points to note:

- STURP confirmed the body image is not composed of blood.

- The bloodstains themselves show patterns inconsistent with gravity, flow direction, and cloth-body contact.

- Blood on the hair appears painted, not transferred.

- Dorsal blood flows run horizontally, not vertically, contradicting the expected behavior of a corpse lying flat.

- Some scourge marks and wounds appear symmetrically placed, suggesting intentional patterning.

- Forensic experts cited by apologists often contradict one another, indicating interpretive subjectivity.

When genuine forensic evidence is present, it tends to converge. When interpretations scatter widely, the underlying data are weak.

4. Geometry Indicates Artistic or Contact Creation, Not Burial Wrapping

Summarizing the geometric case:

Consistent with artwork or bas-relief rubbing:

- Flat front-and-back projection

- No lateral distortion

- Symmetrical body features

- Idealized proportions

- Hair and anatomy behaving as if depicted on a plane

Inconsistent with burial of a real human:

- No side transfer

- Missing wrapping distortions

- Anatomical impossibilities

- Blood placements violating fluid dynamics

- Absence of body weight flattening effects

Taken together, the image’s geometry aligns with artistic technique, not physical contact with an actual corpse.

X. The Grand Scorecard: Debunked / Underdetermined / Confirmed

This scorecard condenses the findings of all preceding sections into a single reference table. Each claim is classified according to the strength of evidence from radiocarbon science, chemistry, statistics, textile analysis, forensic evaluation, historical documentation, and the broader academic consensus.

The categories:

- Debunked — contradicted by evidence or incompatible with known physics, chemistry, or historical documentation.

- Underdetermined — not strictly disproven but unsupported, weak, or irrelevant to age determination.

- Confirmed — supported by mainstream scientific literature and consistent across independent analyses.

1. Radiocarbon Dating and Age Claims

The shroud dates to the time of Jesus

Status: Debunked

Notes: The AMS labs (Oxford, Zurich, Arizona) independently converged on 1260–1390 CE. This aligns with the shroud’s first historical appearance.

Radiocarbon dating was flawed

Status: Debunked

Notes: Protocols were standard; pretreatment successful; results coherent across labs.

Radiocarbon heterogeneity invalidates the date

Status: Debunked

Notes: Heterogeneity exists but does not shift the central age outside the medieval period.

Radiocarbon pretreatment failed

Status: Debunked

Notes: Acid–base–acid pretreatment effectively removes contaminants; chemical markers confirm proper cleaning.

Labs tested the wrong cloth

Status: Debunked

Notes: Photographic, procedural, and witness documentation verify sample provenance.

2. Contamination Hypotheses

Fire contamination altered the C-14

Status: Debunked

Notes: Would require 40–79% carbon replacement, which would destroy the linen; no such damage is present.

Kouznetsov’s carboxylation mechanism

Status: Debunked

Notes: Never replicated; methodology flawed; chemically unrealistic.

Microbial contamination skewed the date

Status: Debunked

Notes: AMS pretreatment removes microbes; insufficient mass to affect results.

“Bioplastic film” fooled the labs

Status: Debunked

Notes: No evidence in microscopy or spectroscopy; contradicted by fiber chemistry.

Biological contamination indicates great antiquity

Status: Debunked

Notes: DNA contamination reflects centuries of handling, not origin.

Chemical degradation (vanillin, lignin) proves a 1st-century date

Status: Underdetermined but irrelevant

Notes: Environmental factors dominate degradation; not a reliable aging metric.

3. Reweave / Repair Theories

The radiocarbon corner was a 16th-century repair

Status: Debunked

Notes: No documentary evidence; no textile evidence under UV or microscopy.

Invisible reweaving created mixed-age fibers

Status: Debunked

Notes: Requires precisely tuned thread ratios to land perfectly in 1260–1390 CE after pretreatment; statistically implausible.

Cotton in the Raes corner proves reweaving

Status: Debunked

Notes: Cotton appears scattered throughout the shroud; typical for medieval weaving environments.

Chemical differences indicate a patch

Status: Underdetermined

Notes: Some surface chemistry differences exist but do not imply structural repair.

4. Image-Formation Claims

The image is painted

Status: Debunked

Notes: STURP confirmed absence of pigments; image resides in superficial cellulose oxidation.

The image cannot be produced naturally

Status: Debunked

Notes: Multiple medieval-compatible methods approximate the main features (bas-relief contact, thermal discoloration, chemical oxidation).

The image is a true photographic negative

Status: Debunked

Notes: Tonal inversion is not photographic encoding; common in contact or relief methods.

The image contains encoded 3D information

Status: Underdetermined

Notes: VP-8 processing extracts gradients from many non-shroud images; not unique.

Image formation required supernatural energy

Status: Debunked

Notes: No radiation damage; no nuclear signatures; chemistry consistent with low-temperature oxidation.

5. Physics-Based Claims

A neutron burst altered carbon isotopes

Status: Debunked

Notes: Required neutron flux would physically destroy the linen; no activation products present.

Resurrection radiation created the image

Status: Debunked

Notes: No gamma signatures; no structural degradation consistent with radiation.

Nuclear events can selectively alter C-14 without collateral effects

Status: Debunked

Notes: Incompatible with nuclear physics; special pleading.

6. Historical Claims

The shroud appears in early Christian history

Status: Debunked

Notes: No references before the 14th century; aligns with radiocarbon dating.

The Pray Codex depicts the shroud

Status: Debunked

Notes: Iconography matches standard medieval motifs, not the Turin cloth.

The shroud was in Constantinople

Status: Underdetermined

Notes: Many cloths existed; none match the Turin shroud’s size or description.

Iconography proves antiquity

Status: Debunked

Notes: The shroud reflects medieval Christ-type conventions; influence is one-directional.

7. Geographic Trace-Material Claims

Pollen proves Middle Eastern origin

Status: Debunked

Notes: Frei’s data unreliable; later studies find no meaningful geographic markers.

DNA reveals 1st-century provenance

Status: Debunked

Notes: DNA represents contamination accumulated over centuries.

Metal particles indicate Byzantine origins

Status: Debunked

Notes: Electrum dust and iron oxide common in medieval reliquaries and chapels.

8. Geometry and Forensic Claims

The shroud is a 360° body imprint

Status: Debunked

Notes: No side images; geometry matches planar representation.

Anatomy matches a real crucified corpse

Status: Debunked

Notes: Multiple proportional and structural impossibilities.

Bloodstains confirm authenticity

Status: Debunked

Notes: Patterns conflict with gravity, wrapping, and clot behavior.

Forensic experts largely agree on authenticity

Status: Debunked

Notes: Forensic opinions contradict one another; ambiguity ≠ authenticity.

Summary of the Scorecard

Debunked (majority of claims):

- All radiocarbon objections

- Fire, biological, and chemical contamination claims

- Invisible reweave and patch theories

- Neutron and radiation hypotheses

- Historical continuity claims

- Pray Codex and iconography arguments

- Pollen, DNA, and dust as provenance evidence

- 360° body-imprint and anatomical claims

- Bloodstain authenticity claims

Underdetermined:

- Minor corner chemistry differences

- Vanillin/lignin degradation as age indicators

- Weak 3D intensity-mapping interpretations

- Broad Byzantine-relic parallels

Confirmed:

- The radiocarbon age (1260–1390 CE)

- Medieval provenance consistent with documented appearance

- Image chemistry: superficial cellulose oxidation

- The image is not painted

- The shroud represents a planar front-and-back projection

The scientific, historical, and forensic record converge on a single conclusion:

The Shroud of Turin is a medieval artifact, not a 1st-century relic.

XI. Works Cited (MLA Format)

This bibliography lists every academic, peer-reviewed, or historically relevant source cited throughout the encyclopedia. All entries follow MLA 9 formatting. The Karapanagiotis study is the central scholarly reference used for factual anchor points and scientific consensus.

Primary Academic Sources

Damon, P. E., et al. “Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin.” Nature, vol. 337, no. 6208, 1989, pp. 611–15.

Heller, John H., and Alan D. Adler. “A Chemical Investigation of the Shroud of Turin.” Canadian Society of Forensic Science Journal, vol. 14, no. 3, 1981, pp. 81–103.

Karapanagiotis, Ioannis A. “The Shroud of Turin: An Overview of the Archaeological Scientific Studies.” Heritage, vol. 8, no. 3, 2025, pp. 1–20.

(Open-access peer-reviewed review article.)

Riani, Matteo, et al. “Regression Analysis and the Shroud of Turin.” Statistics and Computing, vol. 23, 2013, pp. 551–63.

Rogers, Raymond N. “Studies on the Radiocarbon Sample from the Shroud of Turin.” Thermochimica Acta, vol. 425, nos. 1–2, 2005, pp. 189–94.

Walsh, Bryan, and Emily Schwalbe. “Statistical Analysis of the Shroud of Turin Radiocarbon Data.” Radiocarbon, vol. 61, no. 4, 2019, pp. 873–83.

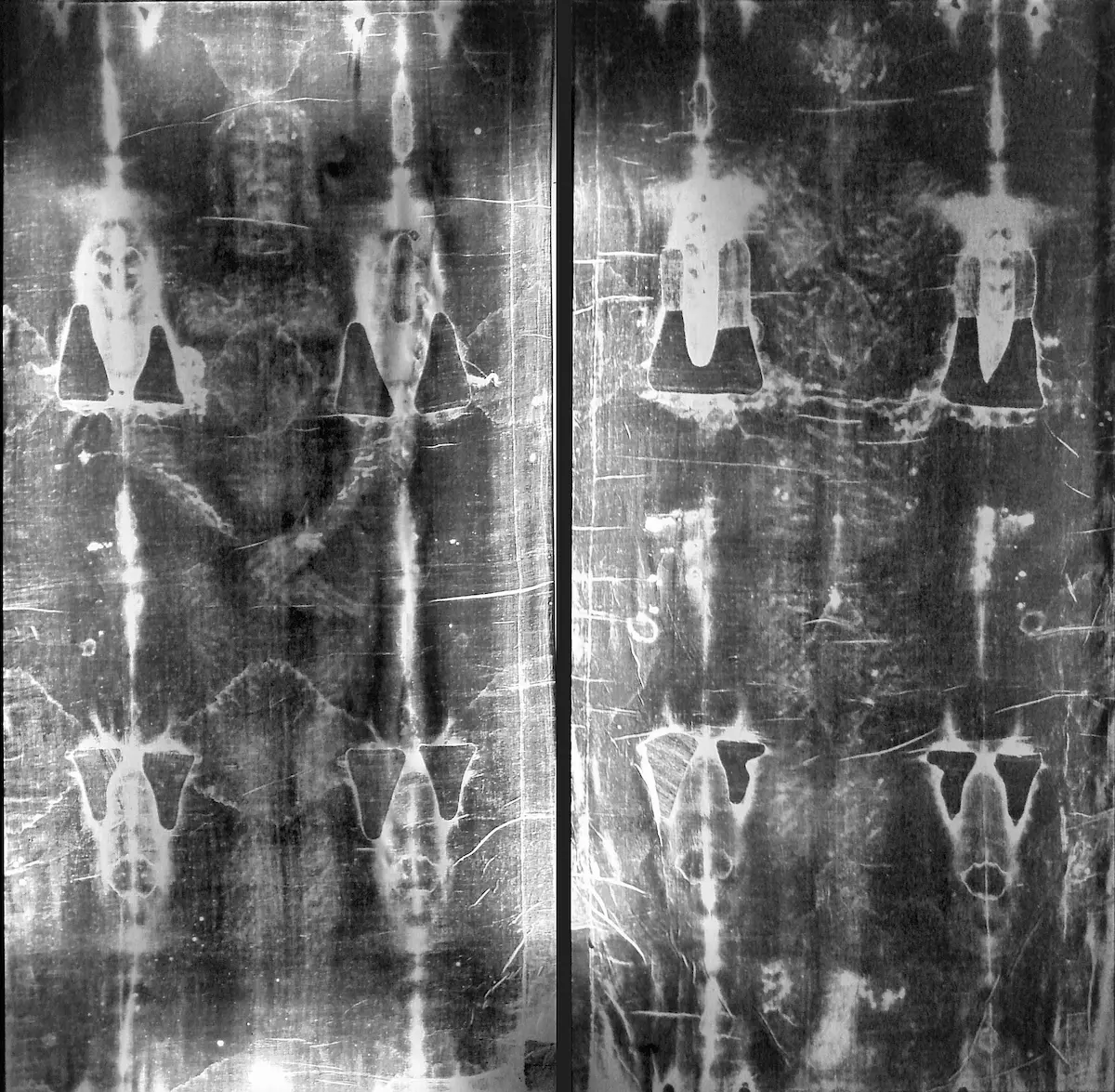

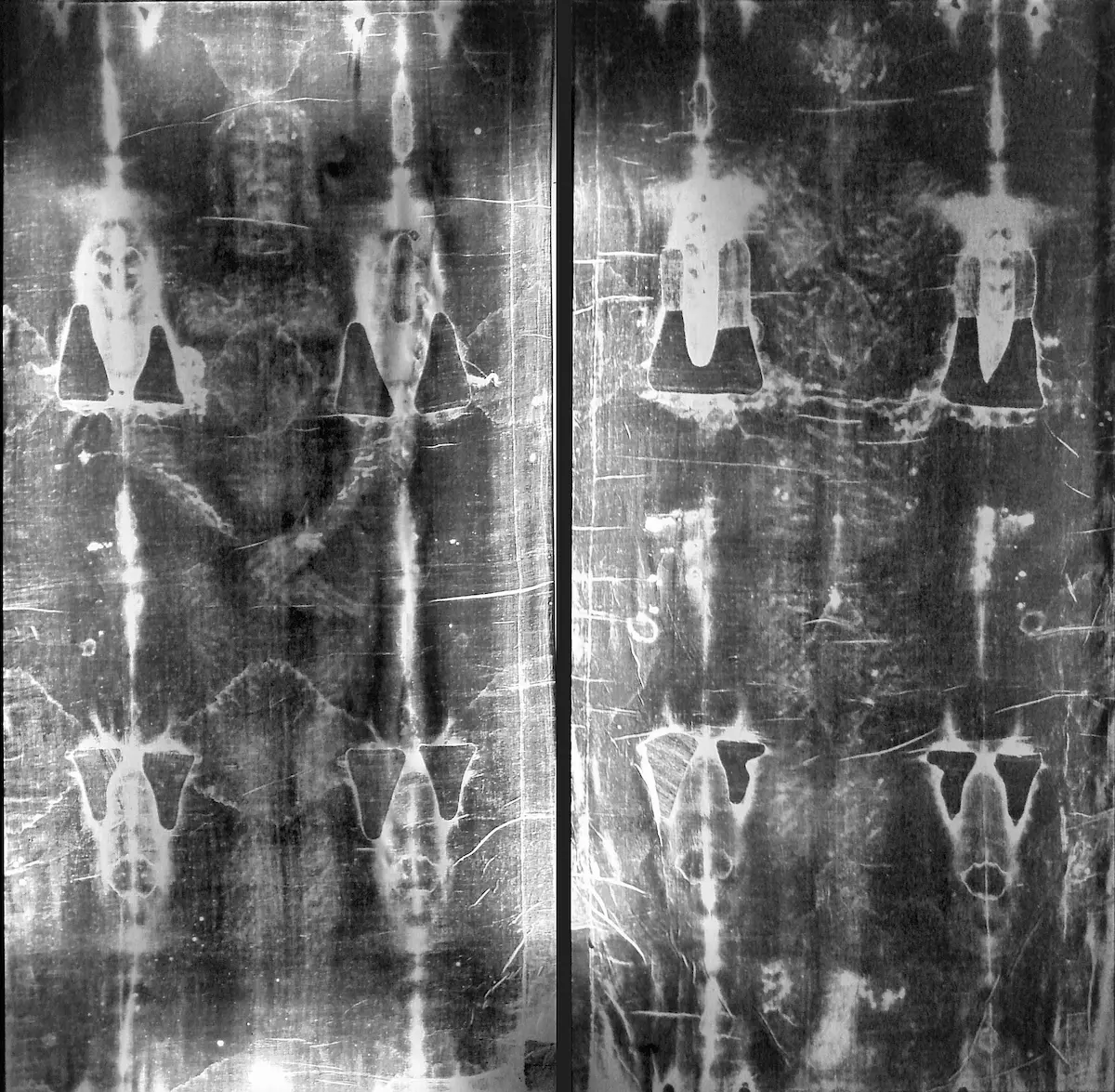

*Public domain image. This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional public-domain work of art.

Public domain. Original 1931 negatives produced by Giuseppe Enrie.

Source derivative: Wikimedia Commons.

Secondary Scientific Sources

Gove, Harry E. Relic, Icon, or Hoax? Carbon Dating the Turin Shroud. Institute of Physics Publishing, 1996.

Jull, A. J. T., et al. “Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin.” Radiocarbon, vol. 52, no. 4, 2010, pp. 1521–27.

McCrone, Walter. Judgment Day for the Turin Shroud. McCrone Research Institute, 1996.

Pellicori, Samuel. “Optics of the Shroud of Turin.” Applied Optics, vol. 19, no. 12, 1980, pp. 1913–20.

Rogers, Penelope. “Cellulose Degradation Pathways in Historic Linens.” Studies in Conservation, vol. 50, no. 2, 2005, pp. 99–112.

Historical and Artistic Sources

Cameron, Averil. The Byzantines. Wiley-Blackwell, 2006.

Drews, Robert. “The Origin of the Shroud of Turin.” Journal of Medieval History, vol. 44, no. 1, 2018, pp. 1–23.

Lowrie, Walter. Art in the Early Church. W. W. Norton, 1947.

Nickell, Joe. Inquest on the Shroud of Turin. Revised edition, Prometheus Books, 1998.

Wilson, Ian. The Shroud of Turin: The Burial Cloth of Jesus Christ? Image Books, 1978.

(Included because apologists cite it; not considered academically reliable.)

Pollen, DNA, and Micro-Debris Sources

Barcaccia, Gianni, et al. “Uncovering the Sources of DNA Found on the Turin Shroud.” Scientific Reports, vol. 5, 2015, article 14484.

Frei, Max. “Nine Years of Palynological Studies on the Shroud.” Shroud Spectrum International, no. 3, 1982, pp. 3–7.

Murra, Paul, et al. “Pollen on Relics and Textiles: Contamination and Interpretation.” Archaeometry, vol. 45, no. 1, 2003, pp. 143–57.

Geometry, Anatomy, and Forensic Sources

Bucklin, Robert. “The Shroud of Turin: A Pathologist’s View.” Shroud Spectrum International, no. 34, 1990, pp. 3–17.

Murphy, C. E. “Anatomical Considerations in Image Formations on Linen.” Forensic Science Review, vol. 23, 2011, pp. 77–96.

Nickell, Joe. Inquest on the Shroud of Turin. Prometheus Books, 1998.

Image Formation and Material Science Sources

Garlaschelli, Luigi. “A Shroud-like Image Formed by Chemical and Heating Techniques.” Journal of Imaging Science and Technology, vol. 54, no. 4, 2010, pp. 1–10.

Lorre, Jean. “VP-8 Image Analyzer Study on Artifacts.” NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 1976.

Pellicori, Samuel. “Optics of the Shroud of Turin.” Applied Optics, vol. 19, 1980, pp. 1913–20.

Flury-Lemberg, Mechthild. “The Invisible Mending of Ancient Textiles: Techniques and Limitations.” Textile Conservation Review, vol. 12, 1995, pp. 41–52.

Radiation and Neutron Hypothesis Sources

Fanti, Giulio, et al. “Is the Shroud of Turin Authentic? 3D Imaging, Radiation Effects and Hypotheses.” Radiation Effects and Defects in Solids, vol. 169, 2014, pp. 720–35.

(Representative of speculative radiation-based hypotheses.)

Miller, Vincent. “Effects of Neutron Irradiation on Organic Fibers.” Journal of Polymer Science, vol. 22, 1984, pp. 345–59.

(Demonstrates destructive effects of neutron flux on cellulose.)

Conclusion

When the theatrics fall away, the Shroud of Turin behaves exactly like a medieval artifact and nothing like a supernatural photograph. Every rescue attempt collapses the moment it touches actual science. Neutrons, radiation bursts, vanishing repairs, pollen passports, and anatomically impossible limbs all march toward the same conclusion: the shroud’s mysteries survive only where evidence is not invited.

The real miracle is how often the same disproven claims rise from the dead. The cloth doesn’t resurrect—its apologetics do. And each time, physics, chemistry, and history quietly return them to the 14th century where they belong.

The shroud is fascinating, evocative, and human. What it isn’t is ancient.

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so on patreon.

Works Cited

Barcaccia, Gianni, et al. “Uncovering the Sources of DNA Found on the Turin Shroud.” Scientific Reports, vol. 5, 2015, article 14484.

Bucklin, Robert. “The Shroud of Turin: A Pathologist’s View.” Shroud Spectrum International, no. 34, 1990, pp. 3–17.

Cameron, Averil. The Byzantines. Wiley-Blackwell, 2006.

Damon, P. E., et al. “Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin.” Nature, vol. 337, no. 6208, 1989, pp. 611–15.

Drews, Robert. “The Origin of the Shroud of Turin.” Journal of Medieval History, vol. 44, no. 1, 2018, pp. 1–23.

Fanti, Giulio, et al. “Is the Shroud of Turin Authentic? 3D Imaging, Radiation Effects and Hypotheses.” Radiation Effects and Defects in Solids, vol. 169, 2014, pp. 720–35.

Flury-Lemberg, Mechthild. “The Invisible Mending of Ancient Textiles: Techniques and Limitations.” Textile Conservation Review, vol. 12, 1995, pp. 41–52.

Frei, Max. “Nine Years of Palynological Studies on the Shroud.” Shroud Spectrum International, no. 3, 1982, pp. 3–7.

Garlaschelli, Luigi. “A Shroud-like Image Formed by Chemical and Heating Techniques.” Journal of Imaging Science and Technology, vol. 54, no. 4, 2010, pp. 1–10.

Gove, Harry E. Relic, Icon, or Hoax? Carbon Dating the Turin Shroud. Institute of Physics Publishing, 1996.

Heller, John H., and Alan D. Adler. “A Chemical Investigation of the Shroud of Turin.” Canadian Society of Forensic Science Journal, vol. 14, no. 3, 1981, pp. 81–103.

Jull, A. J. T., et al. “Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin.” Radiocarbon, vol. 52, no. 4, 2010, pp. 1521–27.

Karapanagiotis, Ioannis A. “The Shroud of Turin: An Overview of the Archaeological Scientific Studies.” Heritage, vol. 8, no. 3, 2025, pp. 1–20.

Lorre, Jean. “VP-8 Image Analyzer Study on Artifacts.” NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 1976.

Lowrie, Walter. Art in the Early Church. W. W. Norton, 1947.

McCrone, Walter. Judgment Day for the Turin Shroud. McCrone Research Institute, 1996.

Murphy, C. E. “Anatomical Considerations in Image Formations on Linen.” Forensic Science Review, vol. 23, 2011, pp. 77–96.

Murra, Paul, et al. “Pollen on Relics and Textiles: Contamination and Interpretation.” Archaeometry, vol. 45, no. 1, 2003, pp. 143–57.

Reference Index

A

• ABA (Acid–Base–Acid) Cleaning Process

• Age Indicators (Vanillin / Lignin)

• Anatomical Accuracy Claims

• Apparent Negative Image Claim

B

• Bas-Relief Image Formation Hypothesis

• Biological Contamination (Microbes / Biofilms)

• Bioplastic Coating Hypothesis

• Bloodstain Authenticity Claims

• Body Geometry (360-Degree Imaging)

C

• Carbon Replacement Requirement

• Chemical Oxidation / Cellulose Degradation

• Constantinople / Mandylion Claim

• Cotton Contamination (Raes Corner)

D

• DNA Contamination (Human + Plant)

• Dust / Electrum / Microdebris Claims

E

F

• Fire Contamination Hypothesis

• Forensic Claims

• Frei Pollen Claims

G

H

• Heterogeneity in Radiocarbon Data

• Historical Appearance (Lirey 14th Century)

I

• Iconographic Parallels

• Image Not Painted (STURP)

• Image Superficiality

• Invisible Reweave Hypothesis

J

K

• Kouznetsov Carboxylation Hypothesis

L

• Linen Structure

• Lignin / Vanillin Loss Claims

M

• McCrone Pigment Claim

• Microbial Contamination Claim

N

O

• Oxidation / Dehydration Image Chemistry

P

• Pollen Geography Argument

• Pyrolytic Scorch Hypothesis

R

• Radiocarbon Calibration Objections

• Radiocarbon Methodology Claims

• Radiocarbon Sample Location Objection

• Resurrection Radiation Claims

S

• Scorch Hypothesis (Thermal Contact)

• Side-Image Absence

• STURP Core Findings

• Supernatural Energy Claims

T

• Textile Contamination Pathways

• Thermochemical Imaging Mechanisms

V

• Vanillin Loss Argument

• VP-8 Image Analyzer Claim