NDE's: Out-of-Body Experiences and the Sensed Presence Can Be Induced

If out-of-body experiences and "sensed presences" are proof of a soul, why can neurologists trigger them with a switch? Discover the specific brain regions responsible for these powerful illusions and the 2014 robotic experiment that manufactured a "ghost" in the lab.

Key Takeaways

Location Is a Calculation: Your sense of being “inside” your body is not automatic. It is an ongoing calculation performed by the brain. When that calculation fails, the brain places the self somewhere else.

The TPJ Switch: Out-of-body experiences can be reliably triggered by stimulating the temporo-parietal junction. Neurologists can shift a patient’s perceived location while the patient remains fully conscious.

Projected Presence: The “sensed presence” is not an external being. It is the brain misattributing its own self-model—a duplicated version of the self projected into nearby space.

The “More Real Than Real” Trap: A powerful sense of realism reflects internal coherence, not external truth. The brain feels confident because it detects no contradiction, not because the event is actually happening.

No Death Required: Because these experiences can be induced in living, healthy people using electrodes, robotics, and exhaustion, they cannot serve as evidence for an afterlife. They are products of functioning brains, not departing souls.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Brain’s Body Map Can Fail

- The Temporo-Parietal Junction Is the Key Site

- The Experience Feels Real Because It Is Coherent

- The Sensed Presence Is a Known Phenomenon

- Why the Presence Feels Meaningful

- Replicability Changes the Conversation

- What This Means for Near-Death Experiences

- Bottom Line

Introduction

Near-death experiences often rest on two claims that feel especially resistant to skepticism.

The first is the out-of-body experience: I was above my body. I saw myself from outside.

The second is the sensed presence: I was not alone. Someone was there with me.

These are not vague impressions. People describe them as structured, coherent, and emotionally powerful. For many, they feel like the strongest evidence that something real—something external—was happening.

The problem is that both experiences are already well known to neuroscience. They do not require death. They do not require trauma. And they do not require anything leaving the body at all.

This article expands on a broader analysis of near-death experiences and brain function. For the central overview establishing why NDEs do not occur in a non-functioning brain, see:

The Brain’s Body Map Can Fail

Under normal conditions, the brain maintains a stable sense of where “you” are. This sense is not generated by a single system. It is constructed by integrating vision, touch, balance, and proprioception.

When these signals align, embodiment feels effortless.

When they don’t, the illusion breaks.

Out-of-body experiences occur when this integration fails. The brain continues to generate a coherent sense of self, but places it in the wrong location. Instead of I am here, the brain concludes I am over there (Blanke and Arzy).

Crucially, the experience does not feel confused or dreamlike. It feels organized. The brain fills in the gaps.

The Temporo-Parietal Junction Is the Key Site

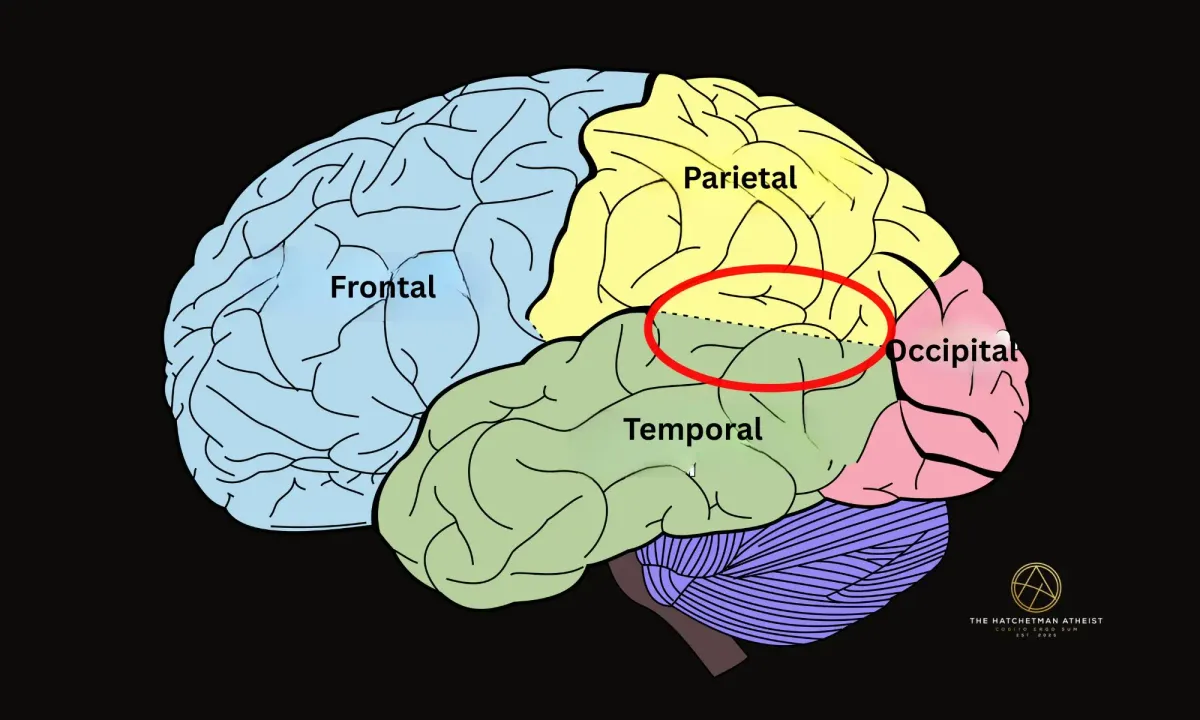

Decades of neurological research point to one region in particular: the temporo-parietal junction (TPJ).

The TPJ sits at the intersection of systems responsible for spatial awareness, body ownership, and perspective. Disrupt it, and the brain’s internal map of the self becomes unstable (Blanke and Arzy).

This is not theoretical.

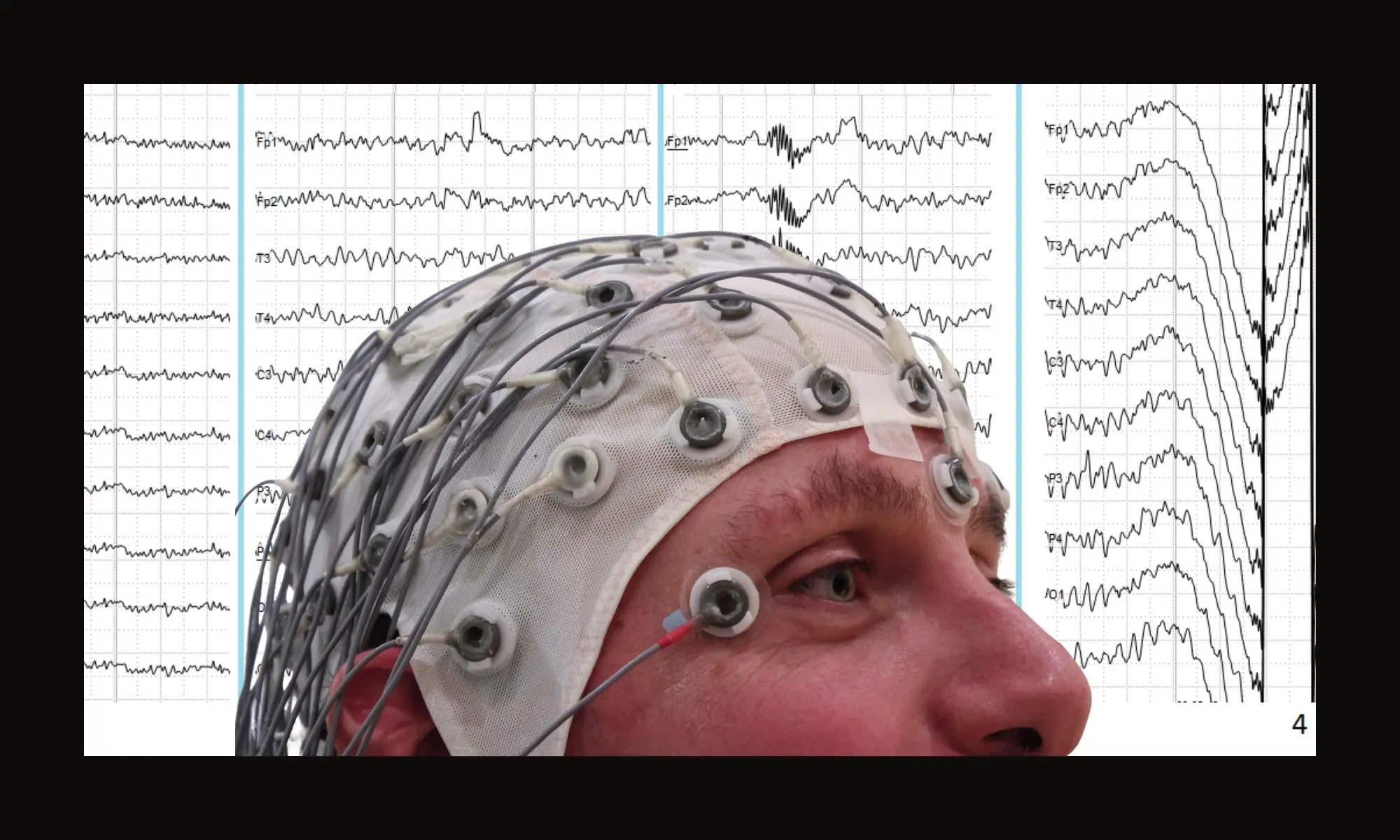

Out-of-body experiences have been induced by electrical stimulation of the TPJ, focal seizures originating near the TPJ, and lesions affecting TPJ connectivity.

In controlled clinical settings, patients have reported floating above their bodies, viewing themselves from behind, or occupying a position displaced from their physical location.

No dying required.

In a landmark clinical case, neurologists induced a vivid out-of-body experience by electrically stimulating the right temporo-parietal junction of a conscious patient. She reported floating above her body and observing herself from an elevated perspective. When stimulation stopped, the experience ended. When stimulation resumed, it returned. Consciousness was never lost. The only variable was targeted disruption of the brain’s body-mapping system (Blanke et al., “Stimulating”).

The Experience Feels Real Because It Is Coherent

Out-of-body experiences are persuasive because they are not chaotic. The brain does not register them as errors. It registers them as perception.

The same predictive machinery that normally stabilizes perception remains active. The brain simply draws a different conclusion about where the self is located.

This is why people describe these experiences as more real than real. The sense of realism comes from internal coherence, not from external accuracy.

Intensity is not evidence.

The Sensed Presence Is a Known Phenomenon

Alongside OBEs, many people report a powerful sense that someone is nearby. This presence may feel protective, watchful, guiding, or threatening.

The interpretation varies. The experience does not.

Neuroscience refers to this as the sensed presence phenomenon. It occurs when the brain misattributes internally generated signals to an external agent (Brugger).

In effect, the brain generates a second self-model and places it just outside the body.

This experience has been reported in neurological disorders, extreme fatigue, isolation, sensory deprivation, sleep paralysis, and laboratory settings.

Once again, no death is required.

In related clinical work, neurologists induced this sensation by electrically stimulating brain regions involved in body representation and self–other distinction while patients were awake and responsive. During stimulation, patients reported the vivid feeling that another person was standing close behind them, often offset slightly to one side and closely mirroring their posture. When the patient moved, the presence moved with them. When stimulation stopped, the presence vanished immediately. Nothing in the environment had changed. The effect depended entirely on disruption of the brain’s internal mapping of self and other (Blanke et al., “Neurological”).

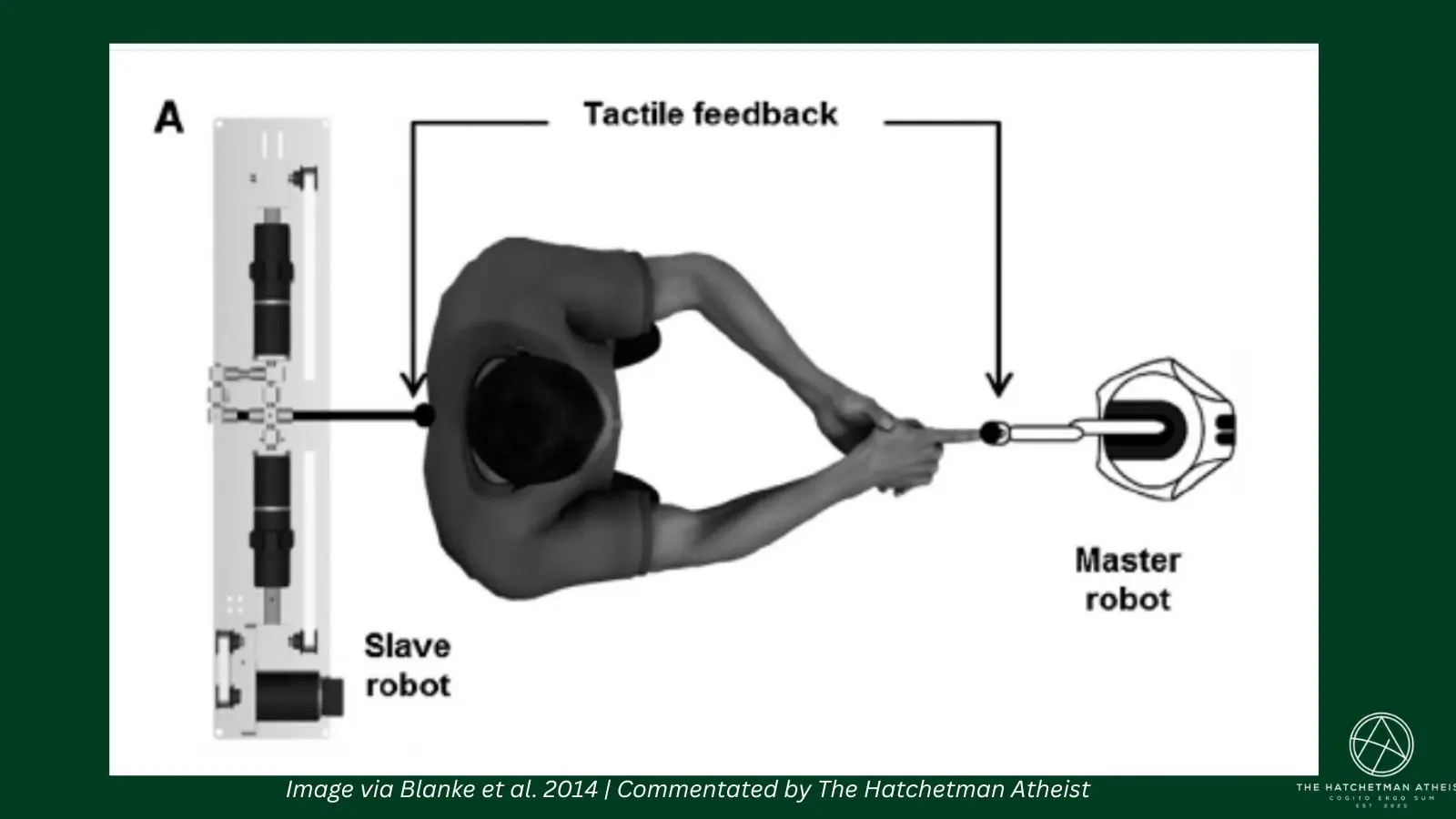

In a related 2014 experiment, participants were asked to move their hand back and forth while controlling a robotic device positioned in front of them. A second robotic arm, placed behind the participant and out of sight, delivered touch to their upper back in response to those hand movements. When the timing was perfectly synchronized, the brain correctly interpreted the sensation as self-generated. But when researchers introduced a slight delay between the participant’s movement and the touch on their back, the brain failed to link the two. Under these delayed conditions, several participants reported the vivid sensation that another person was standing directly behind them, touching them in response to their actions. As soon as normal timing was restored, the presence disappeared.

This same mechanism helps explain why the experience is so often interpreted as a guide, protector, or watcher. The brain supplies the presence; prior belief supplies the identity.

Image adapted from Blanke et al. (2014), Neurological and Robot-Controlled Induction of an Apparition.

Why the Presence Feels Meaningful

Humans are social animals. The brain is constantly modeling other minds. Under normal conditions, those models are anchored to real people.

When sensory input degrades or integration falters, the brain can externalize one of these models without any person present.

The result is not vague unease. It is often a strong, emotionally charged sense of company.

Culture supplies the meaning.

Neurology supplies the experience.

Replicability Changes the Conversation

Experiences that occur spontaneously are easy to mythologize. Experiences that can be induced are harder to treat as evidence of another realm.

Out-of-body experiences and sensed presences can be triggered, studied, disrupted, and reversed.

That does not make them trivial. It makes them explicable.

If the brain can convincingly generate the feeling of leaving the body—and the feeling of not being alone—then those feelings no longer require a supernatural explanation by default.

What This Means for Near-Death Experiences

Near-death experiences often combine multiple elements: bodily detachment, altered perspective, emotional intensity, and perceived companionship.

Post 1 showed that these experiences do not occur in the absence of brain activity.

This post shows that two of their most persuasive features can be generated by the brain itself.

Nothing has been dismissed.

The experiences remain subjectively real.

But they no longer point outward by necessity.

Bottom Line

Out-of-body experiences are not evidence of consciousness leaving the brain.

They are evidence of the brain’s ability to mislocate the self.

The sensed presence is not proof that someone was there.

It is a known effect of how the brain models agency.

Both experiences can be induced without death.

Both are coherent, powerful, and convincing.

Neither requires anything supernatural to occur.

The question is no longer whether these experiences feel real.

It is why the brain is so good at making them feel that way.

More Hatchetman Atheist posts:

If this work has been useful to you, feel free to buy me a coffee.

Works Cited

Blanke, Olaf, and Shahar Arzy. “The Out-of-Body Experience: Disturbed Self-Processing at the Temporo-Parietal Junction.” The Neuroscientist, vol. 11, no. 1, 2005, pp. 16–24.

Blanke, Olaf, et al. “Stimulating Illusory Own-Body Perceptions.” Nature, vol. 419, no. 6904, 2002, pp. 269–270.

Blanke, Olaf, et al. “Neurological and Robot-Controlled Induction of an Apparition.” Current Biology, vol. 24, no. 22, 2014, pp. 2681–2686.

Brugger, Peter. “From Haunted Brain to Haunted Science: A Cognitive Neuroscience View of Paranormal and Pseudoscientific Thought.” In Hauntings and Poltergeists, edited by James Houran and Rense Lange, McFarland, 2001, pp. 195–213.