The Nativity: Luke and the Ten Year Pregnancy

Luke’s Nativity story collapses under its own timestamps: Herod dies in 4 BCE, Quirinius’s census comes in 6 CE, and somehow Mary is pregnant for ten years. A skeptical dive into history, propaganda, and why the Christmas story doesn’t add up.

Harmonizations relied on importing ideas that weren’t there. The only way to harmonize is to add things to the text that the text itself never said. That is not exegesis—that is invention.

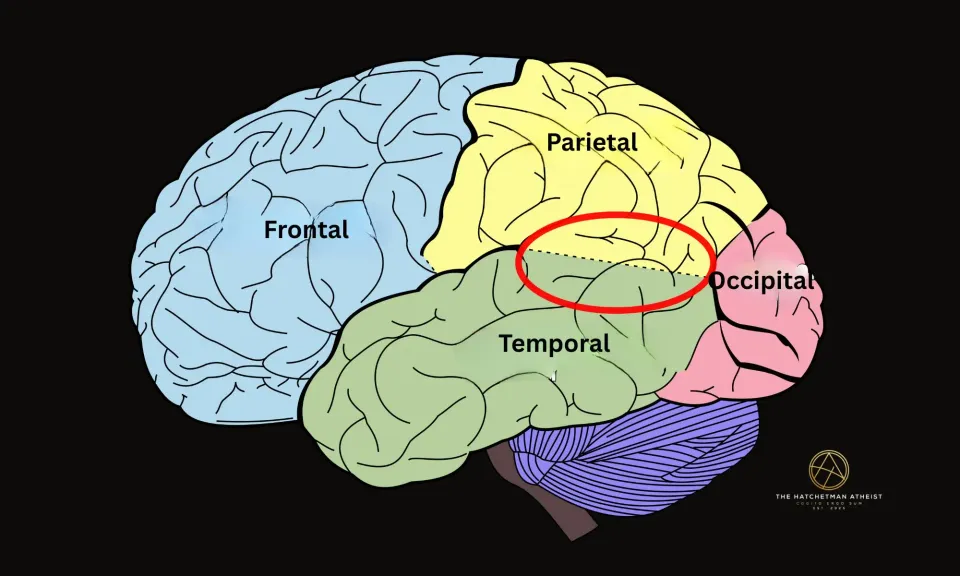

We should start with the hard dates so we know what we are working with, from a historical perspective.

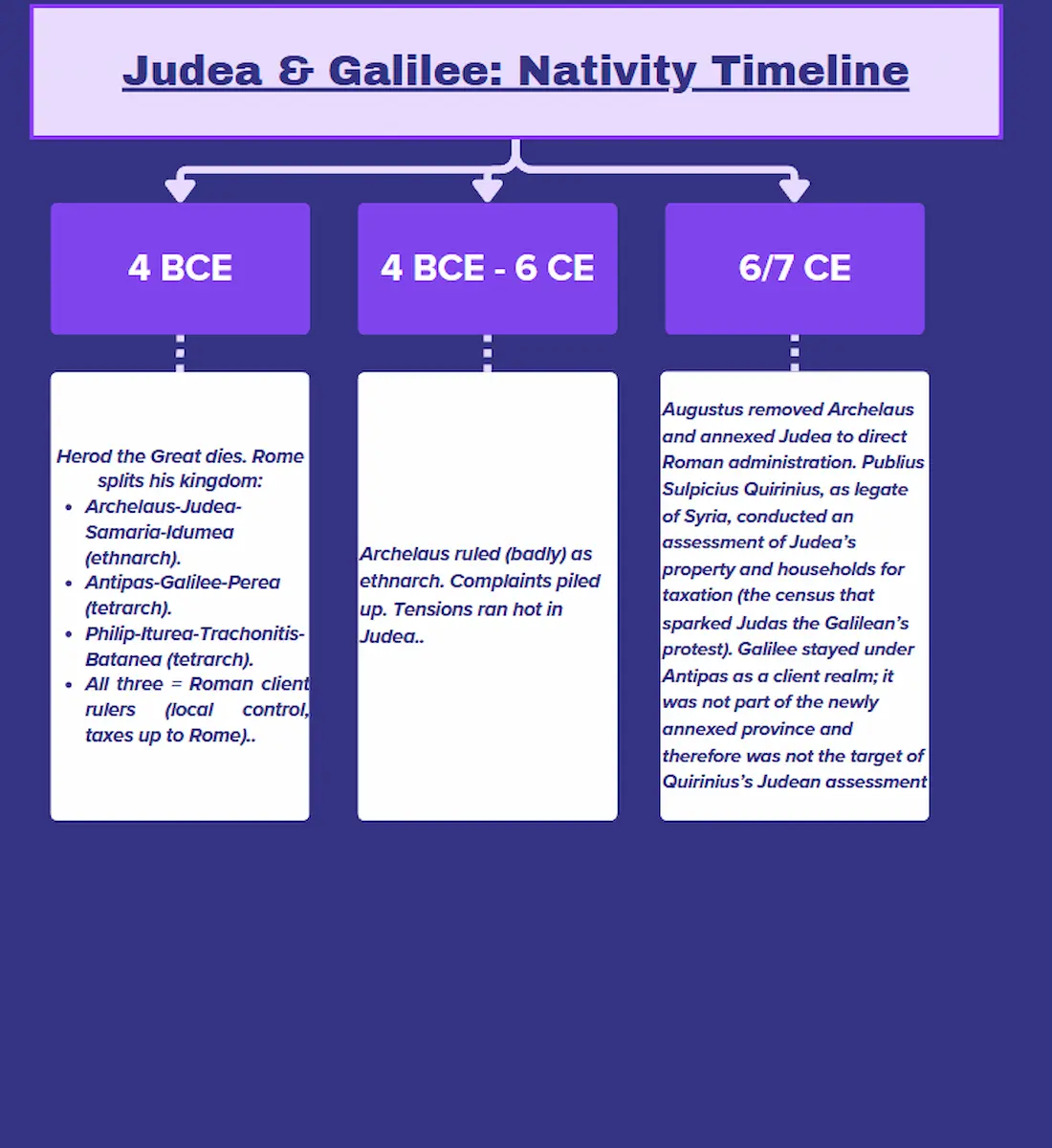

When Herod the Great died in 4 BCE, Rome did not hand his realm to a single heir; it carved it up.

- Archelaus received Judea, Samaria, and Idumea as ethnarch.

- Herod Antipas ruled Galilee and Perea as tetrarch.

- Philip governed the northeastern lands—Iturea, Trachonitis, Batanea—also as tetrarch (Josephus, Antiquities 17; War 2).

These were not full-on kings, though. They were client rulers: local authority, forwarding tribute up to Rome. Archelaus ruled poorly for about a decade until Augustus finally deposed him in 6 CE. Judea was annexed as a Roman province, and Publius Sulpicius Quirinius, legate of Syria, arrived to register property and households for taxation. That census sparked Judas the Galilean’s revolt (Antiquities 18.1–2). Meanwhile, Galilee stayed under Antipas; it wasn’t annexed and was not included in Quirinius’s census.

The titles mattered because they were tiers of power—baby-king grades, if you like. A king (basileus) was a full royal client over a substantial, unified territory; Herod the Great was the poster child, which was why the Bible called him “King Herod.”

An ethnarch—literally “ruler of a people”—sat a notch lower, more than a village chief but less than a crowned client-king. Archelaus got that consolation prize: authority over Judea, Samaria, and Idumea, but not the royal title.

A tetrarch began as “ruler of a fourth,” then drifted into a catch-all label for minor client princes: regional mini-thrones with real local power, small scope, and constant Roman oversight. Antipas and Philip wore that badge.

In short, ethnarchs and tetrarchs were genuine offices, but they were junior-grade sovereigns who ruled under Rome’s umbrella and at Rome’s pleasure.

What Luke Says

Luke plants two timestamps for the nativity.

First: “In the days of King Herod of Judea…” (Luke 1:5, NRSVUE). That sets the story before 4 BCE (the year that King Herod died).

Second: “This was the first registration and was taken while Quirinius was governor of Syria.” (Luke 2:1–2, NRSVUE). That was 6 CE—about a decade later (after ten years of misrule by Archelaus)

Luke even adds the mechanism: Joseph traveled from Nazareth to Bethlehem “because he was descended from the house and family of David” (Luke 2:3–4, NRSVUE).

That’s where the wheels come off.

The Jurisdiction Problem.

Nazareth was in Galilee, which in 6 CE was under Antipas, not Rome. Quirinius’s census applied to newly annexed Judea, not Antipas’s client kingdom. Rome taxed client states indirectly: Caesar billed Antipas, and Antipas squeezed his subjects for the money to pay. No Roman officials counted Galileans. No Galilean carpenter trudged south to Bethlehem for Judea’s census.

If you needed a modern analogy, think borders. The United States ran a federal census to count people inside the United States. Canada, a separate sovereign, was not included. Even if Washington had demanded a fixed annual payment from Ottawa, U.S. census takers would not have fanned out through Toronto condos to count Canadians; Washington would have billed Ottawa, and Ottawa would have figured out how to pay. Likewise, Rome billed Antipas; Quirinius counted Judea. Nazareth was on the Canada side of that analogy.

The “Ancestral Home” Requirement

Luke imagined families scattering back to ancestral towns. Dramatic? Yes. Administrative? No. Roman registrations tracked where you lived and what you owned. Taxes follow property, not pedigree.

The Egyptian papyri prove it. A 104 CE edict of Gaius Vibius Maximus ordered: “The house-to-house census having started, it is essential for all who are away from their nomes to return to their own hearths.” (Hunt and Edgar). Home meant your present domicile—where tax collectors could find you—not your ancestor’s birthplace.

An empire-wide ancestral migration would have clogged roads, shuttered shops, and left bureaucrats counting empty houses. Romans loved order and revenue, not chaos.

The Ten Year Pregnancy of the Virgin Mary

Luke tied himself in knots. He said John the Baptist was six months older than Jesus (Luke 1:26, 36). He placed John’s conception “in the days of King Herod” (before 4 BCE) but Jesus’s birth “when Quirinius was governor” (6 CE). That’s a ten-year gap.

If you already believe in a virgin birth, maybe a decade-long pregnancy doesn’t faze you. But for the rest of us, it’s an obvious contradiction, and Luke supplied both timestamps himself. You can’t stretch six months across ten years without snapping the rope.

Why Tell the Story This Way?

Because Jesus was known as Jesus of Nazareth. But messianic hope demanded Bethlehem, David’s town (Micah 5:2). Matthew solved it by placing the family in Bethlehem from the start. Luke kept them in Nazareth but scripted a Bethlehem birth trip for a census. Both aimed at the same theological target: rebranding Jesus as David’s heir.

But the scaffolding beneath Luke’s version—its dates, its census mechanics, its jurisdiction—doesn’t hold. Josephus was blunt: “[Quirinius] came himself into Judea, which was now added to the province of Syria, to take an account of their substance.” (Antiquities 18.1.1). Judea, not Galilee. A provincial tax roll, not an ancestral pilgrimage.

Luke’s nativity reads less like history and more like propaganda dressed up in official language. It sounded credible. It wasn’t.

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so on patreon.

Works Cited

Bagnall, Roger S., and Bruce W. Frier. The Demography of Roman Egypt. 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Brown, Raymond E. The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke. Updated ed., Doubleday, 1993.

Hunt, A. S., and C. C. Edgar, editors and translators. Select Papyri, Volume II: Public Documents. Loeb Classical Library 266, Harvard University Press, 1934.

Josephus, Flavius. Antiquities of the Jews. Translated by William Whiston, Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. Books 17–18.

— — —. The Jewish War. Translated by William Whiston, Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. Book 2.

The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition. Friendship Press, 2021. Luke 1–2.