The Exodus Poop Problem: The Mathematics of Fecal Deposits

We often look for pottery or weapons as proof of the Exodus. But math suggests we should be looking for something else: 1.3 billion gallons of human waste. Why the archaeology of sanitation makes the biblical narrative a logistical impossibility.

Absence of Evidence, or Evidence of Scale?

Every time a skeptic points out that there is no archaeological evidence for the Exodus, believers often respond with the same apologetic dodge: just because we haven’t discovered it doesn’t mean it isn’t there. And in isolation, that point is fair. The absence of evidence is not, by itself, evidence of absence.

Except when the scale of what we would expect to find is so enormous that not finding it begins to look like more of a miracle than anything described in the Bible.

I am speaking, dear friends, about poop. Human excrement. Feces. Crap.

The Population Problem

According to the Exodus narrative, the Israelites spent close to thirty-eight years camped at Kadesh-barnea before entering the Promised Land. The population is described as roughly six hundred thousand adult males, which—once women and children are included—puts the total somewhere between two and two-and-a-half million people. Let’s be conservative and say 2.4 million.

For any large group of people, sanitation is not a side issue. It is a central logistical constraint, one that nomadic groups and armies have had to manage since prehistory. So how does the biblical text say the Israelites handled this problem?

The Biblical Sanitation Plan

“You shall have a designated area outside the camp to which you shall go. With your tools you shall have a trowel; when you relieve yourself outside, you shall dig a hole with it and then cover up your excrement.” Deuteronomy 23:12–13.

That is the entirety of the solution. Each individual digs a hole by hand and buries their waste. Person by person. Day after day. For decades. In an arid desert environment.

• The Flood Myth: Bigger, Wetter Theology

• The Geological Impossibility of Noah’s Flood

• The Antichrist: Nero, 666, and the Beast

• The Great Silence: Why the Sixteenth Century Forgot the Virgin of Guadalupe

A Note on the “Burial” Logistics

One detail in this instruction is easy to miss unless you stop and visualize the camp itself.

If the population figures in the Exodus narrative are taken seriously, the Israelite camp would not have been a tidy cluster of tents. Estimates by scholars and military historians suggest a population of several million would require a camp anywhere from six to ten miles across.

That means an Israelite living near the center of the camp would have to walk roughly three to five miles just to reach the “designated area outside the camp” every time nature called. Then they would dig a hole by hand, bury their waste, and make the same multi-mile return trip.

This was not a once-in-a-lifetime inconvenience. It was a daily requirement. Sometimes more than once per day. For children, the elderly, the sick, and the injured. For nearly forty years.

The instruction in Deuteronomy doesn’t solve the logistical problem. It quietly magnifies it.

Putting Numbers to the Problem

Let’s put some numbers to that.

If each person relieved themselves once per day and produced a modest average of about 150 milliliters (roughly 0.15 liters, or about 5 fluid ounces), that works out to approximately 360,000 liters of human waste per day, or about 95,000 gallons. Over thirty-eight years—about 13,870 days—that totals about 4.99 billion liters, or roughly 4.99 million cubic meters (about 1.32 billion gallons).

The Footprint

Spread that volume out into a rectangle one foot deep (about 0.3 meters), and you get an area of about 176.3 million square feet. That is about 16.38 million square meters, just over 6.3 square miles, or roughly 4,048 acres — a feature you could see from the air.

And that is just human waste. It does not include animals, which the text says were abundant. It assumes perfect health, no population growth, and only one bowel movement per person per day. It also assumes limitless suitable ground for digging and burial without accumulation, contamination, or reuse of space.

Preservation and Archaeology

It is also worth noting that arid environments are excellent at preserving organic material. Dry conditions slow decomposition dramatically, which is precisely why archaeologists are so good at finding ancient biological remains in desert regions. Desiccated fecal material, latrine pits, and waste deposits left behind by armies, caravans, and large settlements have been identified and studied in arid environments dating back thousands of years. If millions of people lived in one location for nearly forty years and buried their waste daily, we should expect to find enormous latrine fields or concentrated deposits. Not subtle traces. Not ambiguous stains. But industrial-scale biological remains.

Why Sanitation Matters

Sanitation is not optional. It is one of the first constraints that limits how large, how dense, and how long human populations can remain in one place.

Scale Comparisons

To appreciate the scale, consider a few comparisons:

- 4.99 billion liters is enough to fill roughly 2,000 Olympic-size swimming pools

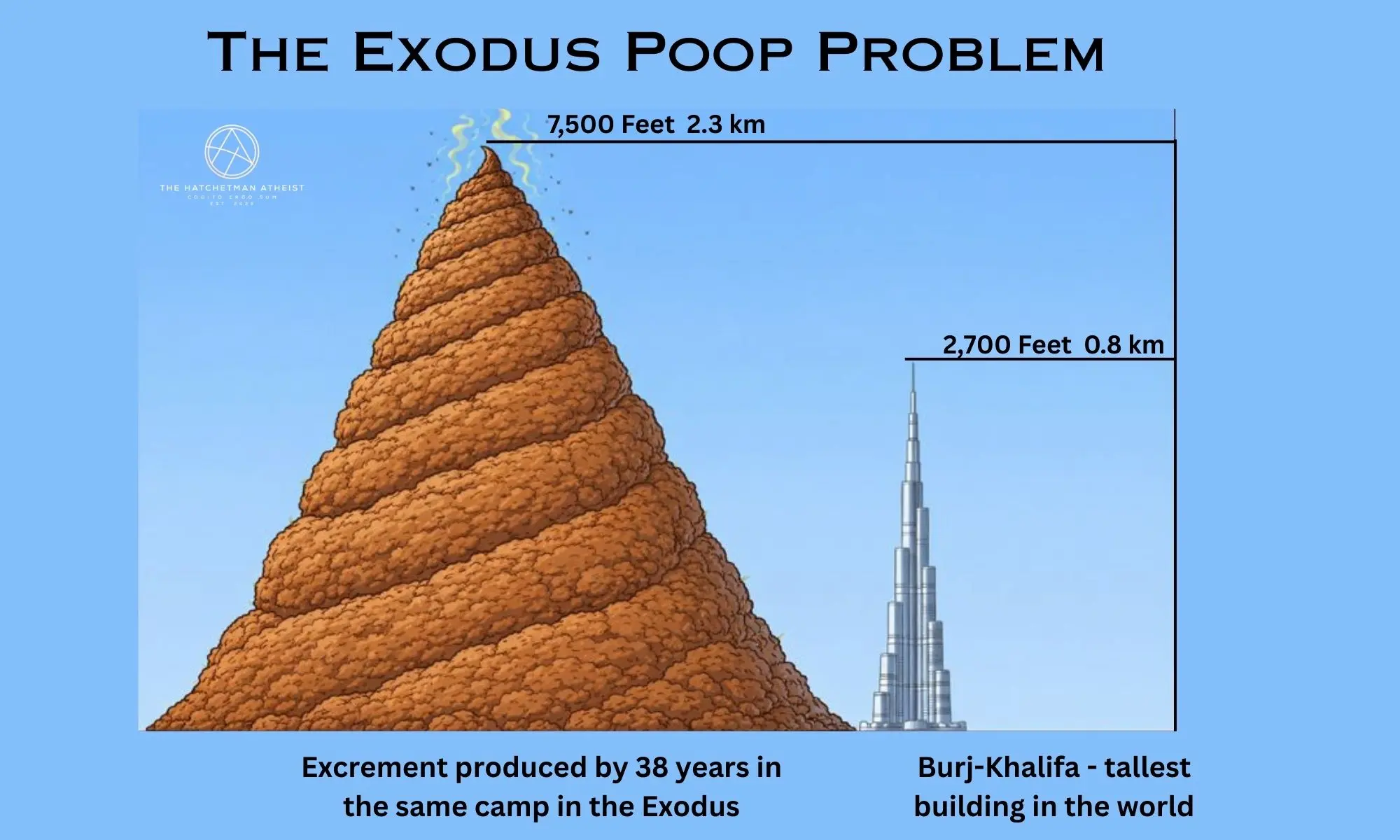

- If you compressed the total into a perfectly packed cone with a circular base 100 yards across, the resulting tower would rise to about 2.28 kilometers (about 7,480 feet). Real piles slump and spread, which means the footprint grows, not shrinks

- In volume, 4.99 million cubic meters is on the order of two Great Pyramids of Giza

- At roughly 360 cubic meters per day, the daily waste output is about 25–50 large dump-truck loads (depending on truck size). Over thirty-eight years, that becomes hundreds of thousands of truckloads

The Inescapable Conclusion

When a story asks us to imagine a city-sized population living in the desert for almost forty years, the problem is not that sanitation is mentioned only once.

It’s that the math never goes away.

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so on patreon.