The Burden of Proof (for Atheists 𝙖𝙣𝙙 Believers)

Who bears the burden of proof—atheists or believers? This essay lays out why it always belongs to the one making the claim, not the one who withholds belief, and unpacks the psychology behind supernatural experiences.

In any honest conversation—especially one that claims to be rational—the rules of discourse matter. Chief among them? The burden of proof. And despite the frantic hand-waving of apologists and internet pseudophilosophers, that burden does not fall on the person who doubts a claim. It falls squarely on the shoulders of the person making it.

Let’s break this down with a little less fog and a little more clarity.

What Is an Assertion?

An assertion is a statement someone puts forward as a conclusion they’ve reached. For instance, “God exists” is an assertion. So is “Aliens built the pyramids,” “Bigfoot lives in Oregon,” and “The moon landing was faked by Stanley Kubrick.” Assertions are, by default, truth claims. They’re statements that the speaker believes correspond to reality.

And with every assertion comes an obligation: support it.

Why? Because simply saying something is true does not make it so. If you’re claiming something about the nature of reality—especially something extraordinary—it’s not up to your listener to disprove it. It’s up to you to demonstrate that it’s reasonable to believe in the first place.

What Makes Evidence Count?

So let’s say the person making the claim does try to offer support. Great. Now we get to dig into the quality of that support.

Is the evidence subjective or objective?

Your personal experience, your feelings, or your faith may feel profound to you, but they don’t function as reliable evidence for others. “I just know in my heart” carries about as much weight in a rational discussion as a horoscope.

Is the logic sound?

We ask: does the conclusion actually follow from the evidence? Is the reasoning free from logical fallacies like circular arguments, special pleading, or appeals to ignorance?

Too often, the “evidence” provided turns out to be a house of cards stacked on assumptions, anecdotes, or theological bias. That’s not evidence. That’s apologetics dressed up for a masquerade ball.

What If You’re Not Making a Claim?

Here’s where people get confused. If someone says, “I don’t believe in God,” that is not the same as saying, “God doesn’t exist.” The former is a withholding of belief, a suspension of judgment until good evidence is provided. The latter is a counter-assertion, and yes—it would also need support.

The skeptic who says, “There is insufficient evidence to justify belief in God,” is not asserting an alternative claim. They’re pointing out the lack of justification for the original one. That’s not a cop-out; that’s critical thinking.

Skepticism, by default, adopts a posture of doubt—not denial. That posture says: “I will believe something when there is adequate evidence to do so, and not a moment before.”

This is not stubbornness. It’s discipline. It’s what keeps us from falling for every charismatic charlatan with a robe and a story.

Why the Burden Matters

Why harp on this? Because in discussions of religion, theists often try to flip the burden of proof. They’ll say things like:

“Well, you can’t prove God doesn’t exist!”

“Atheism is just another belief system!”

“You have faith too!”

No. Just—no.

The inability to disprove a claim is not a valid reason to believe it. I cannot disprove the existence of invisible pink unicorns orbiting Neptune either, but that doesn’t mean I need to justify my disbelief. If a claim is unfalsifiable, it’s also unprovable—and critically speaking, unworthy of serious consideration until something changes.

To demand that skeptics defend their non-belief is to demand they assume a position they have not taken. It’s like asking someone to justify why they don’t believe in horoscopes or homeopathy. The correct answer is, “Because no one has met their burden of proof.”

The Bottom Line

If you’re making a claim—about gods, ghosts, or the great galactic turtle that allegedly supports the cosmos—you have the burden of proof. You have to bring the evidence. You have to show your work. And if you can’t?

Well, then your claim remains what it began as: an assertion, unsubstantiated and unconvincing.

The rest of us will be over here, waiting for something a little more compelling than “just trust me.”

Appendix I: Expert Voices on the Burden of Proof and Rational Belief

1. The burden of proof is on the claimant:

“The burden of proof lies upon him who affirms, not on him who denies.” — Legal Maxim, often attributed to Roman law (De Legibus, Cicero), echoed in modern evidentiary standards.

“The onus of proof lies on the person making the claim—especially when that claim contradicts established knowledge.” — Bertrand Russell, “Is There a God?”, 1952

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” — Carl Sagan, Cosmos, 1980

2. Withholding belief is not a claim:

“An agnostic position is not a positive belief that something does not exist. It is a refusal to grant belief without sufficient evidence.” — Antony Flew, The Presumption of Atheism, 1976

“You cannot prove a negative general existential claim. The best you can do is point out the lack of evidence for it.” — Michael Scriven, Primary Philosophy, 1966

3. Skepticism is the rational starting point:

“It is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.” — W.K. Clifford, The Ethics of Belief, 1877

“Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is absurd.” — Voltaire, Letters on England, 1733

4. Subjective evidence is not persuasive:

“Subjective certainty does not equal objective truth.” — Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion, 2006

“What can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence.” — Often attributed to Christopher Hitchens, God Is Not Great, 2007

5. Belief without evidence is not intellectually honest:

“Faith is believing what you know ain't so.” — Mark Twain, possibly apocryphal but often cited

“A wise man... proportions his belief to the evidence.” — David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, 1748

Appendix II: The Fallibility of Subjective Evidence and Eyewitness Testimony

1. Eyewitness Testimony Is Often Wrong

“The single greatest cause of wrongful convictions in the U.S. is eyewitness misidentification.” — The Innocence Project.

2. Memory Is Not a Recording Device

“Memory does not work like a video recorder. It is malleable and susceptible to suggestion.” — Elizabeth Loftus

3. Confidence Does Not Equal Accuracy

“Confidence is not a reliable indicator of accuracy in eyewitness testimony.” — Gary L. Wells

4. False Memories Can Be Implanted

“People can develop rich false memories for events that never happened, especially when prompted by suggestion.” — Julia Shaw

5. Subjective Experiences Are Non-Transferable

“An experience that convinces one person is not automatically valid evidence for another.” — Michael Shermer

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so here:

Works Cited

The Innocence Project. “Eyewitness Identification Reform.” The Innocence Project, innocenceproject.org/eyewitness-identification-reform/.

Loftus, Elizabeth F. “Planting Misinformation in the Human Mind: A 30-Year Investigation of the Malleability of Memory.” Learning & Memory, vol. 12, no. 4, 2005, pp. 361–366.

Wells, Gary L., and Elizabeth A. Olson. “Eyewitness Testimony.” Annual Review of Psychology, vol. 54, 2003, pp. 277–295.

Shaw, Julia. The Memory Illusion: Remembering, Forgetting, and the Science of False Memory. PublicAffairs, 2016.

Shermer, Michael. The Believing Brain. Henry Holt, 2011.

Appendix III: The Psychology of Supernatural Experience

Subjective supernatural experiences—such as sensing invisible presences, communicating with the dead, or receiving divine messages—have been reported across cultures for millennia. But psychological and neurological research offers a much more grounded explanation for these sensations.

Paranormal Experiences and Executive Function

Some research suggests that paranormal experiences—like sensing presences or supernatural events—correlate with disruptions in executive cognitive functions. Participants who self-identify as having supernatural abilities often score higher on measures of executive function difficulties compared to skeptics.

The Inner Workings of Subjective Paranormal Experiences (SPEs)

A thematic analysis into personal narratives of paranormal experiences identified recurrent elements like sensory vividness, distorted perception of reality, and meaning-making. These experiences often arise at the intersection of perception, interpretation, and a desire to understand the unknown.

Anomalistic Psychology: Natural Roots of "Paranormal" Experience

Anomalistic psychology treats paranormal claims as natural phenomena resulting from psychological and physical factors—like hallucinations or perceptual illusions—rather than supernatural sources. It emphasizes that such experiences can occur in mentally healthy individuals without invoking otherworldly causes.

After-Death Communications (ADCs) and Emotional Healing

Modern surveys show that a significant number of people report encountering after-death communications like hearing a loved one’s voice or feeling their presence—especially during grief. Often, people describe these experiences as surprising but soothing, helping them cope with loss.

Perceived Presence and Brain Stimulation

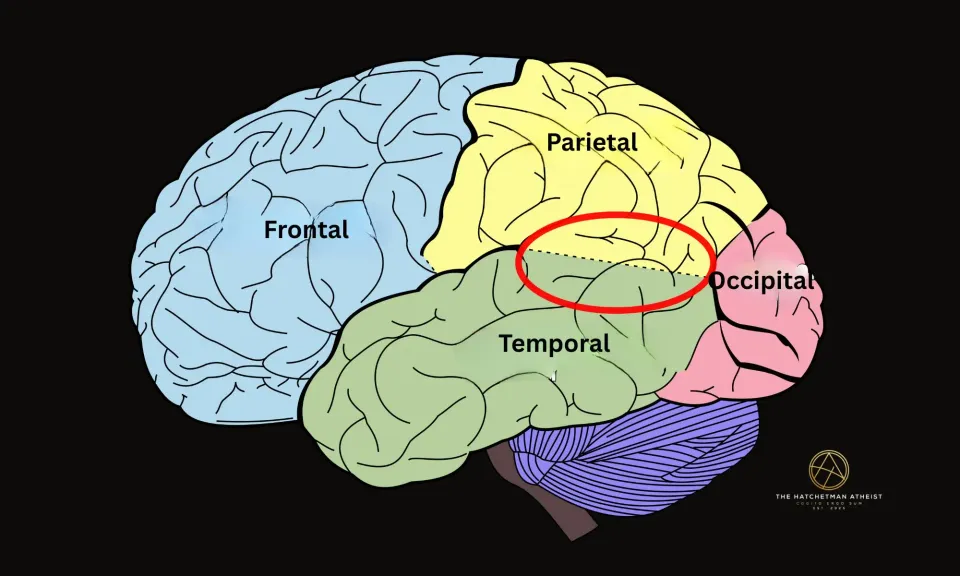

Perhaps the most compelling experiment in this field was conducted by neuroscientist Michael Persinger. Using a device nicknamed the “God Helmet,” Persinger exposed participants to complex magnetic fields targeting the temporal lobes of the brain. A significant number reported feeling an unseen "presence" in the room or a profound sense of being watched. Importantly, the sensations arose without any accompanying stimuli—purely through localized brain stimulation (Persinger 123–126).

False Memories and Imagination Inflation

Elizabeth Loftus and colleagues demonstrated that simply imagining an event can increase the belief that it really happened. In one study, participants asked to picture fictitious childhood events (e.g., getting lost in a mall) were later more likely to insist those events occurred. This “imagination inflation” effect has major implications for memory-based supernatural claims (Garry et al. 208–209).

Eyewitness Inconsistency and Interpretive Errors

Studies of eyewitness testimony have long revealed the unreliability of human perception. In one classic experiment, multiple witnesses observed the same simulated car crash but later gave widely divergent accounts—differing on speed estimates, colors, and sequences of events (Loftus and Palmer 586). This is especially relevant to group supernatural sightings, where each participant's memory may mutate in unique ways.

Bereavement and “Spirit” Visitations

Research published in the British Medical Journal found that 14% of bereaved spouses reported visual hallucinations of their deceased partner, while others described auditory or tactile experiences. Far from signs of pathology, these "ghostly" encounters are now recognized as a psychologically normal part of the grieving process (Rees 37–38).

Absorption and Suggestibility

The personality trait known as absorption—a tendency to become mentally immersed in imagination or sensory experiences—is strongly linked to mystical visions and religious ecstasies. People high in absorption are more likely to report supernatural perceptions, even when no external triggers are present (Tellegen and Atkinson 268).

Hallucinations in Healthy Individuals

Hallucinations aren’t limited to mental illness. A broad survey revealed that about 10% of mentally healthy people report experiencing at least one hallucination—usually under stress, fatigue, or isolation. These include auditory voices, shadowy figures, or vivid visions that feel entirely real at the time (Ohayon 154).

Cognitive Bias and Pattern Recognition

Humans are wired to find patterns—even where none exist. Known as pareidolia, this phenomenon explains why we "see" faces in clouds or "hear" voices in static. Under the right emotional or environmental conditions, this bias can be misinterpreted as divine or paranormal communication (Brugger et al. 114

Works Cited

Brugger, Peter, et al. “Functional Hemispheric Asymmetry and Belief in ESP: Toward a Cognitive Neuroscience of Belief.” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, vol. 12, no. 3, 2000, pp. 114–123.

Garry, Maryanne, et al. “Imagination Inflation: Imagining a Childhood Event Inflates Confidence That It Occurred.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, vol. 3, no. 2, 1996, pp. 208–214.

Loftus, Elizabeth F., and John C. Palmer. “Reconstruction of Automobile Destruction: An Example of the Interaction Between Language and Memory.” Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, vol. 13, no. 5, 1974, pp. 585–589.

Ohayon, Maurice M. “Prevalence of Hallucinations and Their Pathological Associations in the General Population.” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, vol. 188, no. 3, 2000, pp. 154–164.

Persinger, Michael A. “The Neuropsychiatry of Paranormal Experiences.” Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, vol. 5, no. 2, 1993, pp. 122–131.

Rees, W. Dewi. “The Hallucinations of Widowhood.” British Medical Journal, vol. 4, no. 5778, 1971, pp. 37–41.

Tellegen, Auke, and Gilbert Atkinson. “Openness to Absorbing and Self-Altering Experiences (‘Absorption’), a Trait Related to Hypnotic Susceptibility.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, vol. 83, no. 3, 1974, pp. 268–277.