The Arbitrary Logic of Sin and Salvation in Christian Theology

Christianity offers a sweeping narrative: humanity falls, God intervenes, Jesus redeems. It’s a story many find compelling. But when you examine the details—how sin is defined, how salvation works—the logic quickly starts to unravel. What emerges is not a seamless moral structure but a collection of doctrines that often contradict each other, ignore their own precedent, or rely on assumptions never fully explained. From inherited guilt to eternal torment, and blood sacrifice to belief-based salvation, the Christian salvation story often feels like a house built on theological improvisation.

Inherited Guilt: A Moral Nonstarter

Christianity teaches that all people are born guilty because of Adam and Eve’s disobedience. Paul spells this out in Romans 5:12: sin came through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all. This is the basis for original sin—a doctrine that claims we’re not just born flawed, but actually guilty.

Different traditions interpret this in different ways. The Catholic Church teaches that baptism washes away this inherited guilt. The Eastern Orthodox Church doesn’t go that far; it teaches that humanity inherits death and corruption, but not guilt per se. Calvinist theology takes the harshest view: humans are born totally depraved and incapable of seeking good without divine intervention.

But here’s the problem: this guilt is assigned automatically. No choice, no action, no awareness—just existence. That’s not justice. It’s inherited condemnation. If morality means anything, it has to begin with agency. Original sin skips that entirely.

Sin as Contamination, Not Just Choice

Scripture describes sin as more than disobedience. It’s portrayed as a power or force. In Genesis 4:7, God tells Cain that sin is “crouching at the door,” as if it’s an animal ready to pounce. Paul, in Romans 7, writes that sin lives within him, controlling his actions against his will. In Ephesians 2:3, humans are described as “by nature children of wrath.”

Sin, in this framework, isn’t something you do—it’s something you are. You don’t become sinful by sinning; you sin because you are sinful by nature. The idea of personal moral responsibility gets replaced by a kind of inherited defect. You’re guilty before you ever make a decision.

The First Sin: Disobedience Without Understanding

Adam and Eve’s act of eating the forbidden fruit is often framed as the moment sin entered the world. But what did they actually do? They ate fruit—not stolen fruit, not someone else’s food—just fruit from a particular tree. The only thing that made it wrong was God’s command.

And the tree? It was the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. According to Genesis 3:7, Adam and Eve only gained moral awareness after eating. That means they were punished for disobedience before understanding the concept of obedience.

It’s like telling someone not to walk on a patch of grass, without explaining why, and then sentencing them to death when they do. It’s not just excessive—it’s a moral trap. The punishment—suffering, mortality, and the damnation of all future humanity—doesn’t just exceed the crime. It makes no sense if the goal is fairness or learning.

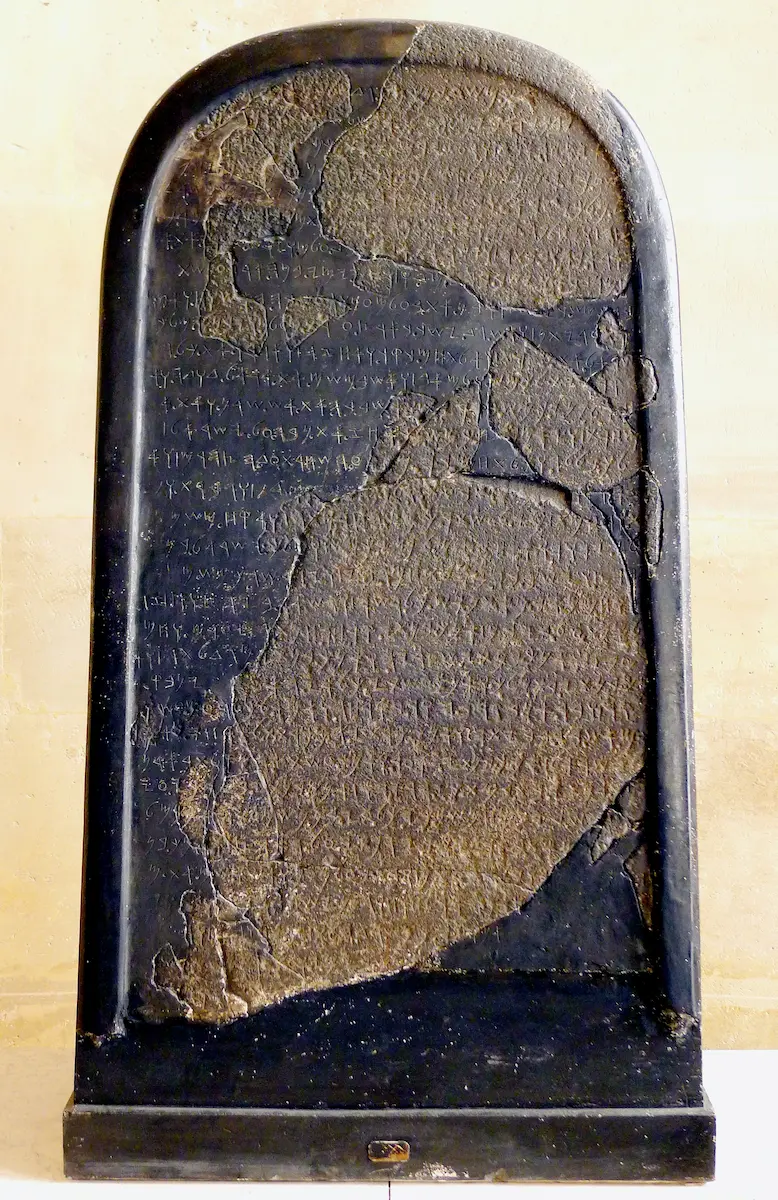

Blood Sacrifice: A Borrowed Tradition

The idea that sin must be atoned for with blood is central to Christian theology. But it doesn’t originate with divine revelation—it comes from culture.

Animal sacrifice was widespread in the ancient Near East long before the Hebrews emerged as a distinct people around 1200–1000 BCE. In Mesopotamia (c. 3000 BCE), Egypt (c. 2600 BCE), and Canaan (c. 2000 BCE), people regularly offered blood—sometimes human, more often animal—to gain favor with the gods, secure fertility, or ward off disaster.

In Genesis 4, Cain and Abel offer sacrifices without ever being commanded to. One is accepted, the other isn’t. No reason is given. In Leviticus 17:11, we’re told that “the life of the flesh is in the blood,” so blood is necessary for atonement. But that’s more poetic than logical. Why blood and not breath? Why not a change of heart?

Placed in context, the Levitical sacrificial system looks less like divine innovation and more like cultural inheritance—another version of what neighboring civilizations were already doing.

Selective Justice: A System with Favorites

The Bible insists that God is just, yet the pattern of justice in Scripture doesn’t hold.

Take David. He commits adultery, arranges a murder, and causes a national catastrophe by ordering a census that leads to 70,000 deaths (2 Samuel 24). And yet, 1 Kings 15:5 says David did what was right “except in the matter of Uriah.” The mass death? The abuse of power? Not mentioned. Entirely ignored.

Meanwhile, other figures are punished instantly for far less. Nadab and Abihu are consumed by divine fire for offering “unauthorized incense” (Leviticus 10:1–2). What does that mean? They burned incense in a way not commanded—perhaps in the wrong place, or with the wrong formula, or at the wrong time. They’re killed for a ritual error.

Then there’s Uzzah. While transporting the Ark of the Covenant on a cart, it hits a bump. The Ark begins to tip, and Uzzah reaches out to steady it. He’s immediately struck dead (2 Samuel 6:6–7). His mistake? Touching a sacred object, even to protect it.

These aren’t examples of consistent, proportional justice. They suggest a god who enforces laws selectively and reacts with extreme force.

Hell and the Logic of Eternal Punishment

Christianity teaches that at the final judgment, the wicked will be cast into a lake of fire for eternal torment (Revelation 20:14–15). But where did Hell come from? Scripture doesn’t say. There’s no creation story for Hell—no explanation for how or why eternal suffering was chosen as the penalty for sin. It simply exists. It’s assumed.

Worse, the scale of punishment is staggering. A person lives for 70 or 80 years and is then punished for eternity. And belief, not behavior, is often the deciding factor. Someone who lives honorably, ethically, and selflessly but never accepts Jesus is lost. A person who lives destructively but repents at the end is saved.

Justice, by any meaningful definition, requires proportionality. Hell, as described, is not justice—it’s retribution on an infinite scale for a finite offense.

Jesus’ Sinless Birth: Theological Gymnastics

If original sin is inherited by all humans, then Jesus—born of a human mother—should have inherited it too. The Bible doesn’t explain how he avoided this. The virgin birth is often cited, but there's nothing in Scripture that says sin is only passed through the father.

To patch this problem, Catholic doctrine created the idea of the Immaculate Conception: that Mary herself was born without sin. Protestants rejected that doctrine but retained the idea that Jesus was sinless. The theological gymnastics required to protect his sinlessness are inventions designed to solve a problem the doctrine itself created.

Sacrifice That Doesn’t Match the Law

Hebrews 10:10 claims that “we have been sanctified through the offering of the body of Jesus Christ once for all.” But when you compare that to the Mosaic Law, the differences are glaring.

Under that law:

- Sacrifices were repeated regularly—daily, weekly, annually.

- They were offered for individual sins, not collective guilt.

- The Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur) was a communal ritual, cleansing the congregation as a whole—but even then, individuals were still required to offer personal sacrifices for their own wrongdoing.

- Most critically, sacrifices only covered unintentional sins. Numbers 15:30 states that high-handed, deliberate sins had no sacrificial remedy.

Jesus’s death, by contrast, is said to cover all sins—past, future, intentional, unintentional—for all people. That’s not continuity. That’s a radical departure.

If God made an exception—allowing one sacrifice to count for all people—why not make a bigger exception? If he can suspend the sacrificial rules for convenience, why not also suspend the rule that sin must be punished with eternal torment? Why require a brutal death at all?

Free Will or Divine Ultimatum?

Christian theology insists that we are free to choose God. But when the alternative is Hell, how free is that choice? That’s not freedom. It’s coercion.

And if angels in heaven sinned, as Christian tradition holds, what stops people from sinning after death—post-judgment, in paradise? Does free will disappear in heaven? Are people reprogrammed? If sin was possible once in paradise, what changed?

The free will argument collapses the moment you try to apply it consistently.

Geography as Destiny

Statistically, most people adopt the religion they were raised with. A child born in Pakistan is likely to become Muslim. One born in Utah may grow up Mormon. In India, Hinduism dominates. In Mississippi, it's Christianity.

Yet Christian theology says that salvation depends on accepting Jesus. That makes salvation feel random. It’s not really about choice—it’s about luck—the winning of the geographic lottery.

What Took So Long?

If sin began with Adam, why did God wait thousands of years to offer a solution? Modern humans have existed for over 200,000 years. Civilization began by 3000 BCE. Jesus arrives in the 1st century CE. What about everyone before him?

If salvation only comes through Christ, then billions of people lived and died without access to it. What purpose was served by the delay?

Belief Over Behavior

Christian theology emphasizes belief over behavior. Ephesians 2:8–9 says salvation is by grace through faith—not works. But this creates a contradiction: someone who lives honorably, ethically, and selflessly without faith is lost. Someone who lives selfishly but believes is saved.

This turns salvation into a loophole. Morality becomes irrelevant. What matters isn’t how you live—it’s whether you believe.

The Scapegoat Problem

Jesus’s death is often described as substitutionary—he took the punishment we deserve. This mirrors the scapegoat ritual in Leviticus 16, where guilt was symbolically transferred to a goat, which was then exiled.

But that wasn’t justice. It was ritual. In modern terms, punishing the innocent to exonerate the guilty isn’t fairness—it’s a moral failure. The idea only works if you already accept the premise that substitutionary punishment is valid.

Scripture as Committee Work

The Bible wasn’t handed down in one piece. It was compiled over centuries, through debate, revision, and political influence. Early Christians disagreed over what should count as Scripture. Books like The Gospel of Thomas, 1 Enoch, The Shepherd of Hermas, and The Apocalypse of Peter were popular in many early communities and seriously considered for inclusion. Some of these texts were even quoted as authoritative by early church leaders.

The final list of canonical books—the Bible as we know it today—wasn’t settled until the late 4th century, during councils like those at Hippo (393 CE) and Carthage (397 CE). Decisions about what to include were shaped by theology, politics, and the desire for uniformity—not by any clear divine directive. If salvation depends on accepting the gospel as revealed in Scripture, and that Scripture was shaped by human committees, historical chance, and ecclesiastical power struggles, the stakes suddenly rest on a shaky foundation.

Postmortem Conversion: Why Not After Death?

If salvation hinges on belief in Jesus and acceptance of the gospel, it’s reasonable to ask: why is that opportunity limited to this life? Why can’t someone accept the truth after death—especially once they’ve been confronted with undeniable evidence of it?

Christianity claims that God desires all people to be saved (1 Timothy 2:4). But it also teaches that once you die, your eternal fate is locked. This seems counterintuitive. If belief is the key requirement, why not allow postmortem belief, once doubt is removed and clarity is possible? If justice and mercy matter, then withholding the possibility of salvation from someone who finally understands—too late—feels arbitrary, even cruel.

If God can override other laws and make exceptions (as he seemingly did with Jesus’ one-size-fits-all sacrifice), why draw an unbreakable line at death?

Conclusion

Christian theology presents itself as a divinely orchestrated solution to the human problem of sin, but its internal contradictions tell a different story. From inherited guilt without choice to eternal punishment without proportionality, the doctrines of sin and salvation often rely on cultural borrowing, selective logic, and theological backflips. Justice is inconsistent, mercy is conditional, and belief is elevated over moral action. The framework doesn’t hold together on its own terms. What emerges is not a coherent divine plan, but a patchwork system—built across centuries, shaped by culture, and held together by tradition more than truth.

Works Cited

- The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition (NRSVue). National Council of Churches, 2021.

- Leviticus 10:1–2; 17:11; Numbers 15:30; Genesis 3–4; 2 Samuel 6:6–7; 2 Samuel 24; Romans 5:12; Romans 7; Ephesians 2:3, 8–9; Hebrews 10:10; Matthew 12:31; Revelation 20:14–15; 1 Kings 15:5; 1 Timothy 2:4.

- Collins, John J. Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Fortress Press, 2018.

- Coogan, Michael D. The Old Testament: A Historical and Literary Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures. Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Ehrman, Bart D. Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Pagels, Elaine. The Gnostic Gospels. Vintage Books, 1989.