Sai Baba and the Nigerian Prince: How Selective Skepticism Curdles Logic in the Christian Mind

Why are Nigerian prince scams rejected instantly while miracle claims are not?

Every adult in the modern world exists under constant epistemic assault.

You are told you can earn $110,000 a year working from home. You are invited into guaranteed investments by distant relatives. You are assured that a stranger has inherited millions and needs only your help to access it.

To survive, you must be skeptical.

You ask:

- Who is making the claim?

- What evidence exists?

- Is the source independent, verifiable, and accountable?

This isn't cynicism; it’s basic cognitive hygiene.

Why do Christians instinctively reject modern miracle claims while accepting biblical miracles supported by far weaker historical evidence?

If you want to see how this pattern of selective skepticism plays out across Christian doctrine and history, these related essays expand the critique:

Everyday Skepticism That Works

Christians deploy this cognitive hygiene successfully every day. They do not wire money to Nigerian princes. They do not accept extraordinary claims from anonymous sources without corroboration.

But then—somehow—they suspend these instincts when it comes to Jesus.

At that point, skepticism ceases to be a virtue; it becomes a vice.

The Problem Isn’t Evidence—It’s Familiarity

Consider the case of Sathya Sai Baba.

Sai Baba was not a literary character or a product of ancient oral tradition. He lived in the twentieth century and died in 2011. We know where he lived, traveled, and is buried. Thousands of living witnesses—doctors, engineers, and journalists—claim to have seen him perform healings, materializations, and even resurrections.

Unlike the miracles of Jesus, several alleged beneficiaries of Sai Baba’s resurrections are named in the modern historical record. You can, quite literally, speak to the people involved.

Christians are rightly skeptical of Sai Baba. They suspect trickery and motivated belief. Yet the evidentiary basis for Sai Baba’s miracles is orders of magnitude stronger than that for Jesus.

The disparity isn't evidence; it's cultural saturation. Christian miracles are inherited and ritualized until they feel inevitable. Sai Baba’s miracles feel foreign, so skepticism is allowed to function normally.

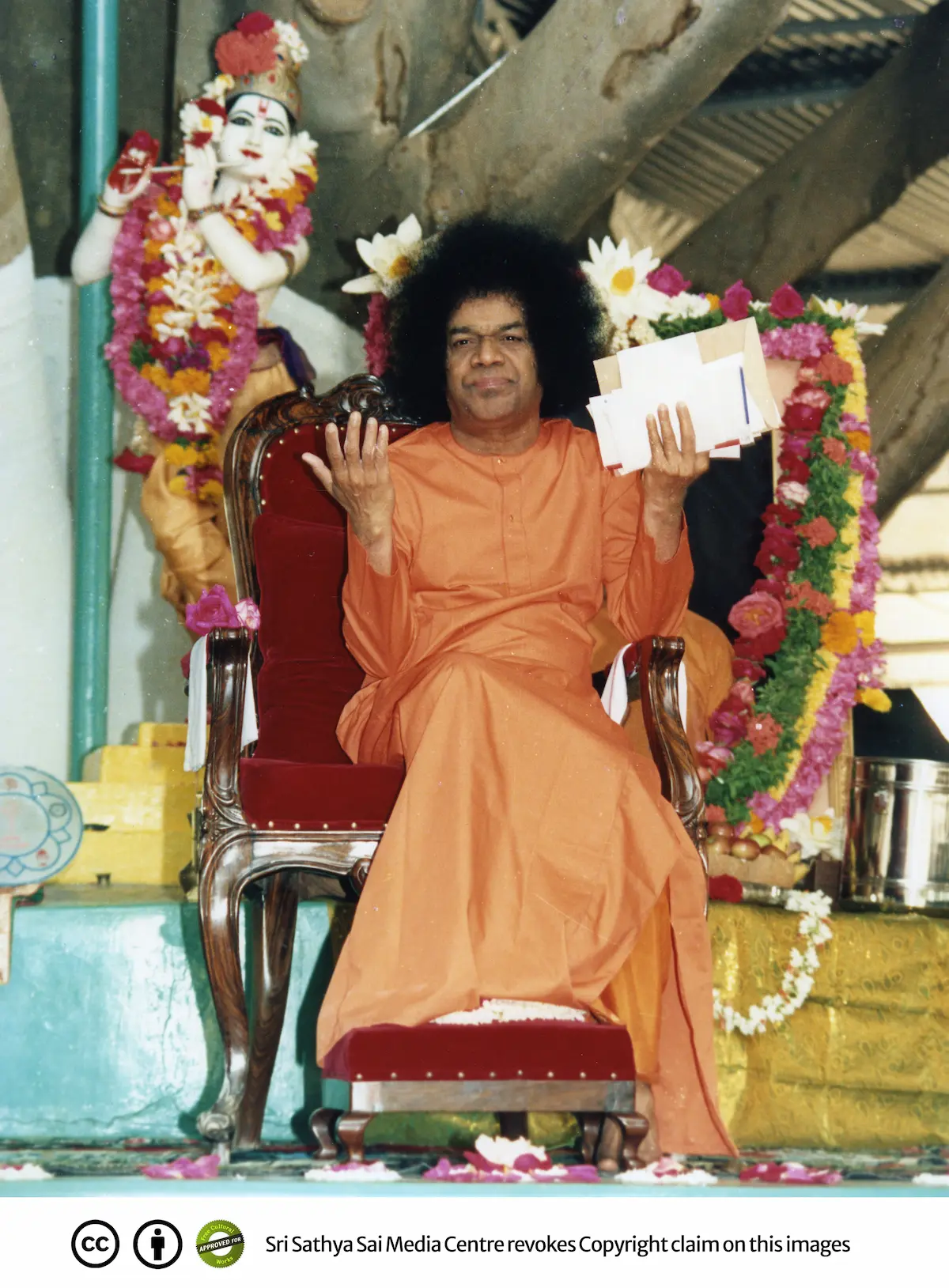

Sri Sathya Sai Baba seated at Brindavan. Photograph by Venkatan, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 4.0.

The Jesus Problem: A Broken Chain of Custody

In any other historical context, chain of custody is everything. But with Jesus, the chain is non-existent:

- No first-hand accounts. Jesus left no writings, and nothing survives written by anyone we can confidently identify as an eyewitness.

- The silence of the state. There are no contemporary Roman or Jewish records describing his ministry or his miracles.

- Anonymous sources. Christianity rests on texts written decades after the fact by unknown authors.

Even Christian scholars admit the manuscript tradition is unstable. Bart Ehrman famously notes that there are more textual variants in New Testament manuscripts than there are words in the New Testament itself. This is not pristine transmission; it is a tradition shaped by centuries of copying, correction, and human error.

Giotto di Bondone, The Raising of Lazarus, c. 1304–1306. Public domain fresco from the Scrovegni Chapel, Padua.

The Devastating Silence of Paul

The earliest Christian author is Paul, writing roughly twenty years after the crucifixion. This is the window where miracle memory should be freshest.

Paul never mentions a single miracle performed by Jesus. No walking on water. No feeding of the five thousand. No raising of Lazarus.

Paul argues relentlessly, defending his authority and theology. Yet he never appeals to Jesus’ earthly miracles as evidence.

This silence is an evidentiary vacuum.

The miracle stories only begin appearing decades later:

- Mark: ~70 CE

- Matthew & Luke: ~80–90 CE

- John: ~90–100+ CE

The trajectory is unmistakable:

Silence → stories → elaboration → theology.

This is not how historical memory behaves. It is how legends grow.

Preference Masquerading as Reason

In every other domain, Christians demand provenance. They care who wrote a document, when it was written, and whether it was altered.

Break that chain and belief collapses—except here.

Here, a broken chain is rebranded as sacred tradition. Modern miracle claims are dismissed not because they lack evidence, but because they threaten theological boundaries.

The Nigerian Prince test proves that Christians know how to be skeptical. They simply refuse to point that lens inward.

Until they do, the double standard remains: evidence is demanded for claims already doubted and excused for claims already believed.

That isn’t faith.

It’s preference masquerading as reason.

Indian postage stamp commemorating the birth centenary of Sathya Sai Baba, issued in 2025. © India Post, Government of India. Licensed under the Government Open Data License – India (GODL).

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so on patreon.

Works Cited

Ehrman, Bart D. Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperOne, 2005.

Luzzatto, Sergio. Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. Metropolitan Books, 2010.