The Resurrection, Fátima, and the Psychology of Memory

Eyewitness testimony fuels stories like the Resurrection and Fatima’s dancing sun. But what if memory—especially in moments of grief and faith—builds miracles from meaning?

Why People Swear They Saw a Miracle—And Might Not Be Lying

Religious mass sightings like the Resurrection or Fatima’s dancing sun aren’t necessarily about fraud or hallucination—they’re about group identity, emotional contagion, and the suggestibility of memory. When belief is strong enough, it doesn’t just color memory. It manufactures it.

Eyewitnesses or Emotional Echo Chambers?

The story of the Resurrection, at least as told in 1 Corinthians 15:6, seems cut-and-dried. Paul claims that Jesus “appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time, most of whom are still alive” (NRSVue). To a modern reader, this sounds like a slam dunk for credibility: five hundred witnesses, living contemporaries, direct memory transmission.

But this statement, written about two decades after the alleged events, is more complicated than it looks. Paul gives no names. No corroborating testimony. No location. Just a number—500—and a vague assurance that some of them are still available to chat. As biblical scholar Dale C. Allison points out, this kind of memory transmission isn’t a simple relay race of facts, but something far murkier.

Allison writes, “Visions and revelations were common in the ancient world and especially among religious people… What may have happened is that some of Jesus' followers had visionary experiences, which were then shared, elaborated, and interpreted theologically until they became accepted as bodily appearances” (Allison 319). What began as grief-induced visions may have solidified into collective memory—cemented by the needs of a traumatized community and the pressure of apocalyptic expectation.

When Memories Are Built, Not Retrieved

To understand how a group might sincerely believe in a miraculous appearance without deliberate deception, we have to turn to cognitive psychology. Elizabeth Loftus, one of the most influential memory researchers of our time, has demonstrated that “memory is not like a video recording—it's more like a Wikipedia page. You can go in and change it, and so can other people” (Loftus and Ketcham 72).

This is especially true when strong emotions are involved. Trauma, grief, and religious ecstasy are not conducive to cool-headed observation. Instead, they open the door to memory distortion, confabulation, and suggestibility. In a famous study by Loftus and Palmer (1974), participants watched footage of a car crash and were asked how fast the cars were going when they “smashed” versus “hit” each other. Those who heard “smashed” reported significantly higher speeds and even imagined broken glass that didn’t exist. Words shaped memory.

Now imagine a crowd of grieving followers, convinced their teacher had fulfilled divine prophecy, gathering to pray and worship. One person sees something—perhaps in a trance or a dream—and says Jesus appeared to them. Another person, already primed by expectation, begins to see the same. Over time, these reports get reinterpreted through the lens of theology: Jesus didn’t just appear; he bodily rose from the dead.

Case Study: Fatima and the Dancing Sun (1917)

Fast-forward to October 13, 1917, near the small town of Fatima, Portugal. Tens of thousands gathered, having been promised by three shepherd children that the Virgin Mary would perform a miracle. Reports varied: some said the sun danced, others that it zigzagged or emitted rainbow colors. Some saw nothing at all. Yet over time, a standard narrative emerged—a miraculous confirmation of the children's visions.

Chris Maunder, a specialist in modern Marian apparitions, explains: “The lack of consistency among observers actually enhances the sociological value of the event. What matters is not what was seen, but that people agreed it was miraculous” (Maunder 97). The miracle became less about observation and more about interpretation. The Church, aware of the ambiguous data, cautiously endorsed the devotion but avoided strict definitions of what actually happened in the sky.

Case Study: Lourdes and the Peasant Visionary (1858)

In 1858, a young peasant girl named Bernadette Soubirous claimed to see the Virgin Mary in a grotto near Lourdes, France. Over a series of apparitions, she was told to dig in the dirt, where a spring eventually emerged—soon believed to possess healing properties.

Medical professionals descended on Lourdes to examine claims of miraculous cures. While some healings were documented, most were anecdotal or psychosomatic. Historian Ruth Harris notes that “belief in the healing power of Lourdes spread rapidly, even when cures could not be medically verified. The act of pilgrimage and collective belief often preceded the cure” (Harris 134). In other words, people believed not because of the evidence—but the evidence was interpreted through the belief.

Case Study: Medjugorje and the Vision That Wouldn’t End (1981–Present)

In the small Yugoslavian town of Medjugorje, six children claimed to have seen the Virgin Mary on a hillside. The visions began in 1981 and—according to some of the seers—continue to this day. The content of the messages has often been apocalyptic, warning of future disasters and urging repentance.

Despite initial skepticism from Church authorities and inconsistencies in the testimonies, millions of pilgrims have traveled to Medjugorje. The Vatican has not authenticated the visions but has allowed pilgrimages, signaling a delicate balance between managing popular belief and withholding doctrinal approval.

Sociologist Michael Cuneo observes, “The strength of the Medjugorje phenomenon lies not in its theological clarity but in its experiential pull. People go, have intense emotional experiences, and come back changed. That is more than enough to build a movement” (Cuneo 189).

Case Study: The Great Disappointment (1844)

Case Study: The Great Disappointment (1844)

In the 1840s, American preacher William Miller predicted that Jesus would return to Earth on October 22, 1844. Tens of thousands of followers—known as Millerites—gathered to await the Second Coming. The date came and went. Nothing happened.

But rather than abandoning the movement, many believers reinterpreted the event. They concluded that Christ had entered the heavenly sanctuary on that date to begin a new phase of salvation history. This reinterpretation birthed what is now the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

As historian Paul Boyer writes, “The failure of the prophecy did not destroy the movement—it refined it. The disappointment was turned into a spiritual vindication” (Boyer 92). This is a textbook case of what Leon Festinger later defined as cognitive dissonance reduction—when a prophecy fails, believers often double down, reinterpreting the event to preserve their identity.

Was That You, Jesus? When Memory Rewrites the Cast List

Was That You, Jesus? When Memory Rewrites the Cast List

One of the most curious features of the post-resurrection stories in the New Testament is how often Jesus’ followers fail to recognize him. In the Gospel of John, Mary Magdalene encounters him at the tomb but mistakes him for a gardener until he speaks her name (John 20:14–16). In Luke, two disciples walk and talk with him on the road to Emmaus without realizing who he is until he breaks bread with them (Luke 24:13–35). In another account, Jesus appears to several disciples fishing on the Sea of Galilee, but they only recognize him after a miraculous catch of fish and breakfast by the shore (John 21:4–12). Even Thomas, famously skeptical, refuses to believe until he touches Jesus’ crucifixion wounds (John 20:24–29).

These scenes are rich with symbolism and theological meaning, but they also raise an unsettling question: if this was the same man they had followed for years, why didn’t anyone recognize him?

One plausible explanation is that these stories represent retroactive reinterpretations of mundane or emotionally intense events that took place shortly after Jesus’ death. Initially, these encounters may not have seemed miraculous. They might have been dreams, visions, or ordinary conversations that gained new meaning only after belief in the resurrection took hold. As biblical scholar Dale C. Allison notes, “visions or dreams that were originally ambiguous or non-specific may have been reinterpreted in hindsight, as the theological conviction that Jesus had risen became widespread” (Allison 319).

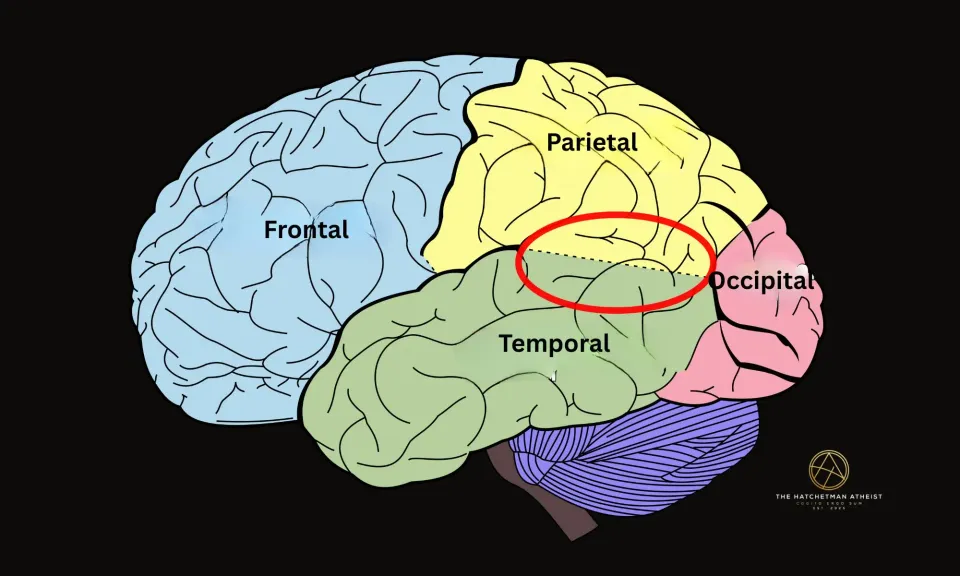

This fits neatly within the psychological concept of source monitoring error—when people misremember the origin or significance of a memory. According to memory expert Elizabeth Loftus, emotional intensity and repeated social reinforcement can not only distort the details of a memory, but also its source, making people believe that an internal image or a vague recollection was something objectively witnessed: “Our memories are constructive. They are built and rebuilt. Emotion and suggestion work hand in hand to reshape what we think we saw” (Loftus and Ketcham 72).

In the weeks following the crucifixion, the early Jesus movement was not only grieving, but struggling to reconcile the catastrophic death of their messianic leader with their conviction that his mission had not failed. It is entirely plausible that this community, primed by messianic expectation, apocalyptic hope, and grief, began to reinterpret recent emotional experiences—such as a dream, a compelling stranger, or a shared meal—as postmortem encounters with Jesus. Over time, these reinterpretations solidified into stories.

The theological stakes were high, but so were the social incentives. To be one of the few who had seen the risen Lord was to be elevated in authority and spiritual prestige. The Gospels themselves suggest a hierarchy of witnesses: Mary is honored, the disciples are gathered and reaffirmed, and Thomas’ doubt is used as a foil to highlight the superior faith of those who believe without seeing. In such an environment, it’s not difficult to imagine that ambiguous experiences would be remembered, retold, and retrofitted to support resurrection faith.

And what of Paul’s claim in 1 Corinthians 15:6 that Jesus appeared to more than five hundred people at once? This number appears nowhere else in the New Testament. No Gospel author mentions it—not even in the lengthy resurrection narratives of Luke or John. Most scholars agree that Paul is citing a different oral tradition than the Gospels. Whether this tradition was metaphorical, visionary, or theological is unknown, but the absence of corroboration suggests it was not drawn from a widely circulating eyewitness account.

Psychologist Daniel Schacter, in his work on memory, explains that “memories that serve identity and belief systems are often preserved even at the cost of accuracy. They are not lies, but reflections of how we want to see ourselves, and how we wish to remember” (Schacter 125). The resurrection stories, particularly those involving the unrecognized Jesus, may represent the transformation of ordinary moments into sacred memory—not out of deceit, but out of need.

If belief in the resurrection came first, these narratives may not be evidence of what happened. They may be evidence of how memory responds when faith demands meaning.

Works Cited

Allison, Dale C. Resurrecting Jesus: The Earliest Christian Tradition and Its Interpreters. T&T Clark, 2005.

Boyer, Paul. When Time Shall Be No More: Prophecy Belief in Modern American Culture. Harvard UP, 1992.

Cuneo, Michael. The Smoke of Satan: Conservative and Traditionalist Dissent in Contemporary American Catholicism. Oxford UP, 1997.

Harris, Ruth. Lourdes: Body and Spirit in the Secular Age. Viking, 1999.

Loftus, Elizabeth, and Katherine Ketcham. The Myth of Repressed Memory: False Memories and Allegations of Sexual Abuse. St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

Maunder, Chris. Our Lady of the Nations: Apparitions of Mary in 20th-Century Catholicism. Oxford UP, 2016.

Schacter, Daniel L. The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers. Houghton Mifflin, 2001.

Wright, N.T. The Resurrection of the Son of God. Fortress Press, 2003.