Was Jesus a Myth?: Post-Crucifixion Mentions of Jesus:

Ancient history is built from letters, hostile notices, and administrative asides—not eyewitness memoirs. This essay examines the post-crucifixion sources for Jesus. Here's what the sources really say.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Primary and Secondary Sources (in Plain Terms)

- The Gospels: Dates, Authorship, and Eyewitness Claims

- Paul: Primary for the Movement, Secondary for Jesus

- Josephus: The Most Contested Non-Christian Source

- Greco-Roman Writers of the Early Second Century

- No Primary Source—and Why That Is Not Unusual

- Works Cited

- Appendix: Scriptural References Mentioned in This Article

This article is part of a four-post series examining Jesus through the lens of historical method rather than theological expectation. Related essays:

When historians ask whether Jesus existed, they are not asking for certainty in the modern sense. They are asking what sources survive, how close those sources are to the events they describe, and what kind of sources they are. Ancient history is built from letters, later narratives, hostile notices, and administrative asides—not eyewitness memoirs preserved in climate-controlled archives.

What follows is a sober look at the post-crucifixion sources for Jesus, beginning with the gospels, then Paul, then Josephus, and finally other Greco-Roman references up through the mid-second century. Along the way, one distinction matters more than any other: the difference between primary and secondary sources.

Primary and secondary sources (in plain terms)

A primary source comes from someone directly involved in or closely connected to the events described. A secondary source reports on events indirectly, relying on testimony, tradition, or earlier reports. The same author can function as both, depending on what is being discussed.

This distinction does not sort sources into “true” and “false.” It sorts them into what kinds of questions they can responsibly answer. Confusing these categories is one of the most common errors in popular discussions of Jesus.

The gospels: dates, authorship, and eyewitness claims

The four canonical gospels—Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John—are our longest narratives about Jesus. They are also among the latest major sources in the source-tradition for Jesus, meaning they were written decades after the events they describe, not that they were the last books written in antiquity.

Most critical scholars date them roughly as follows:

Mark: around 70 CE

Matthew: around 80–90 CE

Luke: around 80–90 CE

John: around 90–100 CE

Even on generous dating, all four gospels are at least one generation removed from the crucifixion. That time gap does not render them useless, but it makes direct eyewitness authorship improbable.

Anonymous texts and later attributions

All four gospels circulated anonymously for decades. The familiar names attached to them appear only in second-century tradition. Internally, none of the texts identify their author.

Luke makes this explicit in his opening lines:

“Since many have undertaken to set down an orderly account of the events that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed on to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word …” (Luke 1:1–2)

This is not the voice of an eyewitness. It is the voice of a compiler working with received traditions.

Clarifying Mark and Luke

A clarification is necessary here, because many readers implicitly assume that all gospel authors are being evaluated as potential eyewitnesses. This is not the case. Mark and Luke were not apostles, and no early Christian tradition claims they were personal followers of Jesus. Even if the traditional attributions were entirely correct, neither author would qualify as an eyewitness. Luke explicitly distances himself from eyewitness status, presenting his work as a compilation based on earlier testimony. Mark, likewise, is never identified with any member of the Twelve. As a result, questions about whether Mark or Luke were the actual authors of their respective gospels do not materially affect the eyewitness argument; neither text claims, nor requires, direct apostolic authorship to function as a source built from earlier tradition.

Literacy, language, and social class

The traditional attributions also strain plausibility when measured against first-century realities.

Acts describes Peter and John as ἀγράμματος—commonly translated as uneducated or illiterate (Acts 4:13). Yet the Gospel of John is written in sophisticated Greek and framed with concepts that resonate with Greek philosophical discourse: logos, light versus darkness, truth versus falsehood. Whatever else this gospel is, it is not the spontaneous literary output of an Aramaic-speaking Galilean fisherman without extensive education or scribal mediation.

Matthew’s traditional identification as a tax collector does not solve the problem. While tax work could involve some Greek, it did not require the ability to compose a long, rhetorically complex Greek narrative saturated with scriptural exegesis. Collecting taxes from Aramaic-speaking locals does not require fluency in Greek any more than assembling Toyota automobiles requires speaking Japanese. Bureaucratic bilingualism exists, but it does not necessarily exist at the bottom rung.

Taken together, these considerations support the mainstream conclusion: the gospels are later theological narratives rooted in earlier traditions, not eyewitness biographies.

Paul: primary for the movement, secondary for Jesus

The undisputed letters of Paul, written roughly between 50 and 60 CE, are the earliest surviving Christian texts. They predate the gospels by decades and therefore deserve careful attention.

Paul is a primary source for the early Jesus movement. He participated in it, argued within it, and personally interacted with its leadership. He is a secondary source for Jesus himself, because he did not follow Jesus during Jesus’ lifetime and does not claim personal acquaintance with him.

Paul is explicit about his early contacts:

“Then after three years I did go up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas (Peter) and stayed with him fifteen days; but I did not see any other apostle except James the Lord’s brother.” (Galatians 1:18–19)

This passage places Paul in contact with named leaders of the movement at an early date and treats James, the Lord’s brother as an unremarkable identifier, not a symbolic title.

Paul’s testimony about Jesus: an exhaustive overview

Paul is not a biographer, but he is not silent either. Across the undisputed letters, he provides multiple, independent data points that presuppose a recent historical person.

He describes Jesus as “born of a woman, born under the law” (Galatians 4:4), locating him firmly within Jewish society. He refers to James as Jesus’ brother (Galatians 1:19) and later mentions “the brothers of the Lord” as known figures (1 Corinthians 9:5). He repeatedly names Cephas (Peter) as someone he knows personally (Galatians 1–2; 1 Corinthians 15:5).

Paul consistently presents Jesus as executed by crucifixion (Galatians 3:1; 1 Corinthians 1–2; Philippians 2:8), attributing responsibility broadly to “the rulers of this age” (1 Corinthians 2:8). He shows little interest in trial mechanics or Roman legal procedure, which is a limitation of his testimony, but not a negation of it.

In 1 Corinthians 15:3–8, Paul quotes a tradition he says he received: that Jesus died, was buried, was raised, and appeared to named individuals and groups. The value of this passage is not theological proof, but its demonstration of an established tradition circulating very early and anchored to specific people.

Paul also occasionally appeals to remembered teachings of Jesus: on divorce (1 Corinthians 7:10–11), on missionary support (1 Corinthians 9:14), and on the Last Supper tradition, explicitly dated to “the night when he was betrayed” (1 Corinthians 11:23–26).

Taken together, Paul’s letters presuppose a recent historical individual with family members, associates, a mode of execution, and remembered teachings—even though Paul shows little interest in Jesus’ public ministry.

Josephus: the most contested non-Christian source

The Jewish historian Flavius Josephus wrote Antiquities of the Jews around 93 CE. Two passages mention Jesus.

One, in Antiquities 20.9.1, refers to “James, the brother of Jesus who is called Christ.” This passage is widely regarded as authentic. Josephus uses Jesus only as an identifier to distinguish which James he means, suggesting the reference required no explanation for his audience.

The second passage, known as the Testimonium Flavianum (Antiquities 18.3.3), survives in a clearly Christianized form that cannot plausibly be original. It declares Jesus to be the Christ and affirms resurrection—claims Josephus nowhere else makes.

Most scholars conclude that this passage was interpolated by later Christian scribes but that a shorter, neutral core originally existed. A commonly accepted reconstruction reads:

“At this time there appeared Jesus, a wise man. He was a doer of startling deeds, a teacher of people who receive the truth with pleasure. He won over many Jews and many Greeks. When Pilate, upon hearing him accused by men of the highest standing among us, condemned him to be crucified, those who had loved him from the first did not cease. And the tribe of the Christians, so called after him, has still to this day not disappeared.”

Further support for a non-confessional version appears in an Arabic chronicle preserved by Agapius of Hierapolis, which paraphrases Josephus as describing Jesus as a wise and virtuous man executed under Pilate, whose followers reported post-death appearances. While late, this witness aligns closely with the reconstructed neutral core rather than the overtly Christian Greek text.

Greco-Roman writers of the early second century

Roman sources begin mentioning Jesus and the Christian movement in the early second century, not as theology but as a social and administrative problem.

Tacitus, writing around 116 CE, states that Christus was executed under Tiberius by Pontius Pilate (Annals 15.44). Tacitus is hostile, precise, and uninterested in Christian belief, which makes his testimony valuable despite its lateness.

Pliny the Younger, governing Bithynia, describes Christians singing hymns to Christ “as to a god” and refusing to renounce him (Letters 10.96). This tells historians nothing about Jesus’ life, but a great deal about how quickly devotion to him crystallized.

Suetonius mentions disturbances among Jews instigated by “Chrestus” during the reign of Claudius. While confused, this likely reflects early disputes within Jewish communities over the Jesus movement.

These authors are not eyewitnesses. They are independent, unsympathetic, and writing for bureaucratic reasons rather than apologetic ones.

No primary source—and why that is not unusual

There is no primary source for Jesus. No inscription, no contemporaneous biography, no diary, no Roman administrative record written during his lifetime. That fact should be stated plainly.

What mitigates this absence is not faith, but context. Jesus was a non-elite, provincial figure who left no writings and was executed as a troublemaker. Figures of this type routinely leave no direct trace.

Paul, while a secondary source, is unusually early and unusually well connected. He personally knew Jesus’ closest associates and members of his family within a few years of the crucifixion. That level of proximity is rare in ancient history.

Comparable gaps exist for other influential figures. Pythagoras left no writings and is known only through later followers. Hippocrates, the foundational figure of Greek medicine, is buried under layers of later attribution and legend. The Buddha is attested only through traditions recorded long after his death, yet few historians conclude he did not exist.

History does not grant certainty. It grants probability constrained by evidence. On that basis, the post-crucifixion sources for Jesus are neither exceptional nor empty. They are precisely what one would expect for a marginal Jewish preacher executed by the state and remembered—imperfectly—by the movement that survived him.

Works Cited

Ehrman, Bart D. The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. 7th ed., Oxford University Press, 2016.

Josephus, Flavius. Jewish Antiquities. Translated by Louis H. Feldman, Harvard University Press, 1965.

Tacitus. The Annals. Translated by Michael Grant, Penguin Classics, 1996.

Pliny the Younger. Letters. Translated by Betty Radice, Harvard University Press, 1969.

Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars. Translated by Robert Graves, Penguin Classics, 2007.

Vermes, Geza. Jesus the Jew: A Historian’s Reading of the Gospels. Fortress Press, 1981.

Allison, Dale C. Constructing Jesus: Memory, Imagination, and History. Baker Academic, 2010.

The Holy Bible. New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition.

Agapius of Hierapolis. Kitab al-‘Unvan (Book of the Title). Quoted in Shlomo Pines, “An Arabic Version of the Testimonium Flavianum,” Proceedings of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, vol. 2, no. 1, 1971, pp. 1–34.

Appendix: Scriptural References Mentioned in This Article

The following scriptural references are included as historical texts cited or discussed in the essay, not as theological authorities.

Gospel Sources

Luke 1:1–2

Luke states that his gospel is a compiled account based on earlier eyewitness testimony, not a firsthand report.

Acts 4:13

Peter and John are described as uneducated or illiterate (ἀγράμματος), relevant to questions of apostolic literary authorship.

Pauline Sources (Undisputed Letters)

Galatians 1:18–19

Paul reports meeting Cephas (Peter) and James, identified as the brother of Jesus.

Galatians 4:4

Jesus is described as being born as a human within Jewish law.

1 Corinthians 9:5

Paul refers to “the brothers of the Lord” as known individuals within the movement.

1 Corinthians 11:23–26

Paul recounts the Last Supper tradition and dates it to the night of Jesus’ betrayal.

1 Corinthians 15:3–8

Paul cites a received tradition describing Jesus’ death, burial, and post-death appearances to named individuals.

1 Corinthians 2:8

Paul states that Jesus was crucified by “the rulers of this age.”

Philippians 2:8

Jesus is described as having been executed by crucifixion.

Romans 1:3

Jesus is associated with Davidic lineage in early Christian tradition.

Image Credits

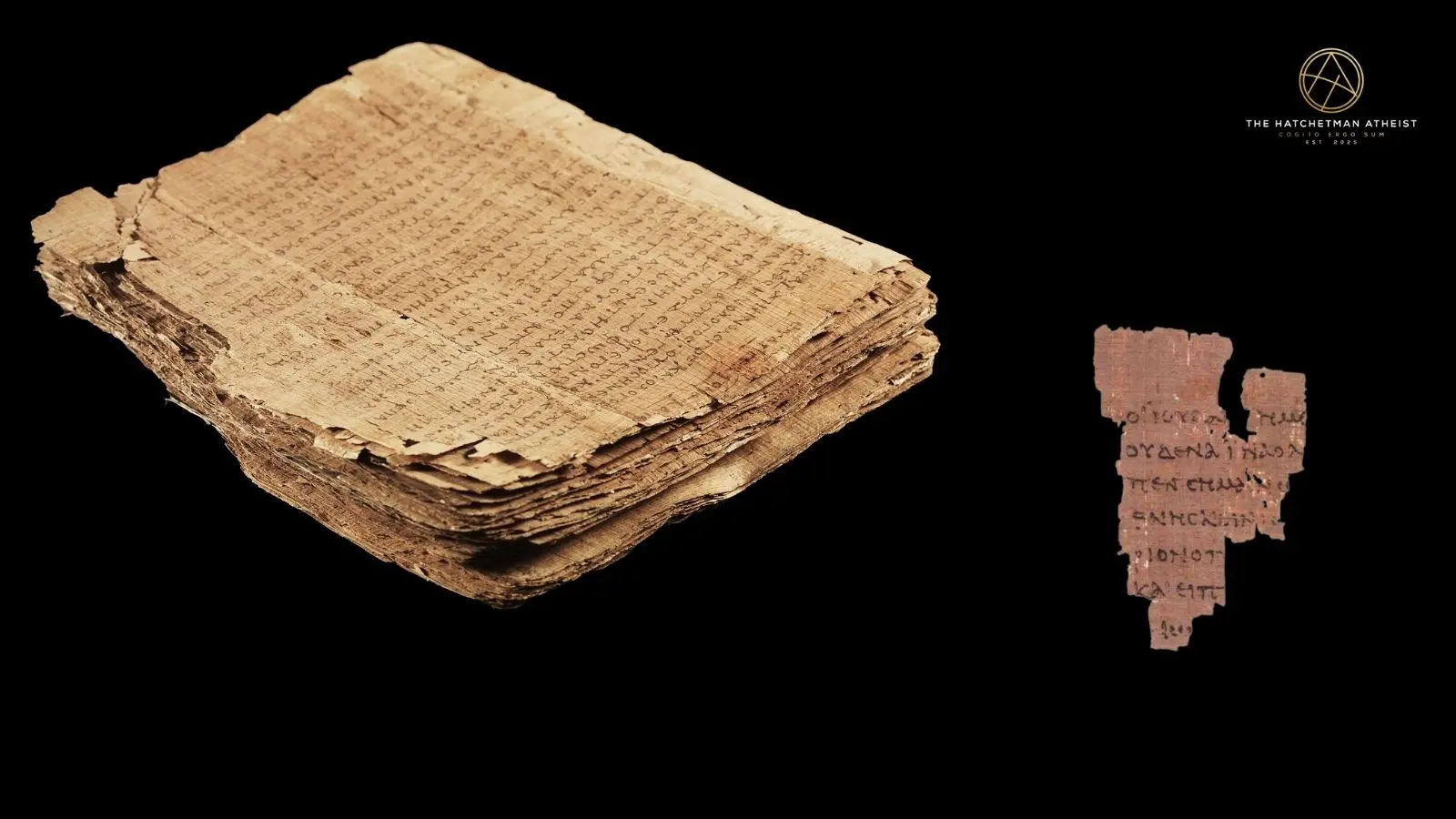

Inline image

Left: Papyrus 66 (𝔓66), folio 1 recto, containing portions of the Gospel of John (2nd century CE). Public domain. Source image via Bodmer Lab / Bibliotheca Bodmeriana; photograph reproduced via Wikimedia Commons.

Right: Rylands Library Papyrus 52 (𝔓52), recto, containing John 18:31–33 (early 2nd century CE). Papyrus held by the John Rylands Library. Public domain. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

This composite consists solely of faithful photographic reproductions of public-domain manuscripts. No new copyright is claimed.

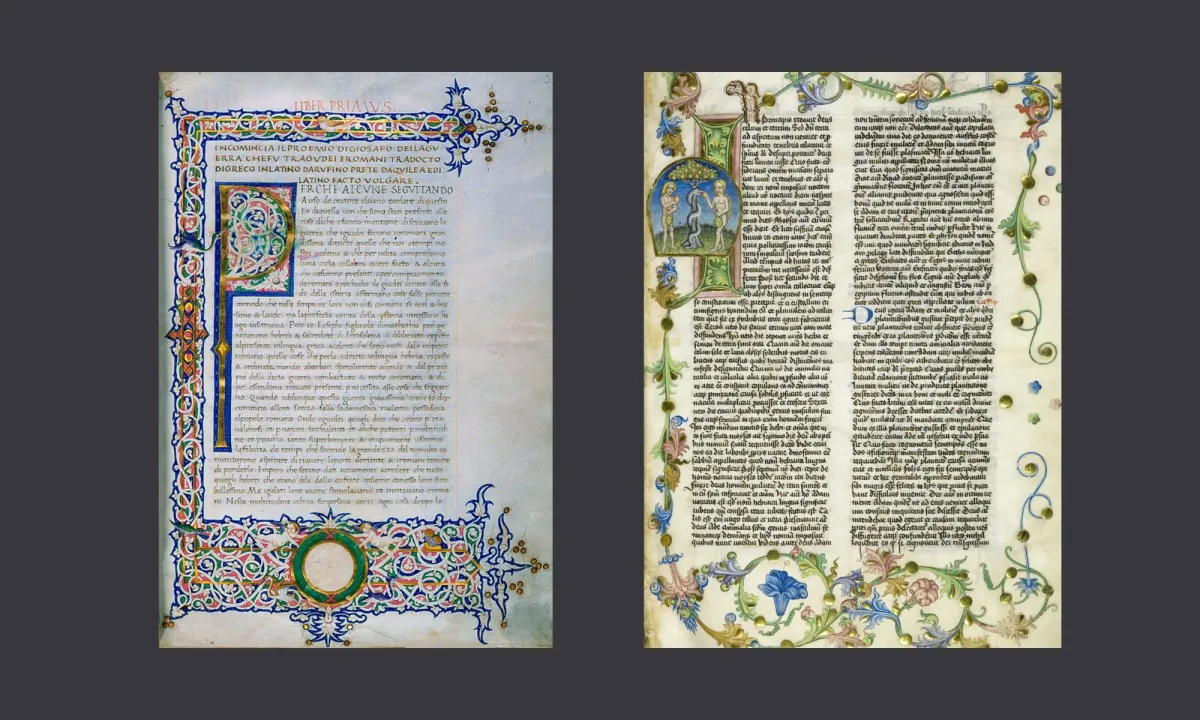

Header image

Left: Illuminated manuscript page from The Jewish War, Italian translation, MS Gar. 15, fol. 3r, produced in Italy in the second half of the 15th century. Manuscript held by the John Work Garrett Library, Johns Hopkins University. Public domain. Digital image via Digital Scriptorium / Wikimedia Commons.

Right: Illuminated manuscript page from Antiquities of the Jews by Flavius Josephus, Book XIX, produced in 1466. Manuscript held by the National Library of Poland, Warsaw. Public domain. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

This composite consists solely of faithful photographic reproductions of public-domain manuscripts. No new copyright is claimed.