Padre Pio's Stigmata Debunked

A clear, skeptical walkthrough of Padre Pio’s stigmata and other claims—what sources actually say, how the stories spread, and where the record is solid versus blurry.

Bleeding for a Blessing? A Closer Look at Padre Pio’s Stigmata

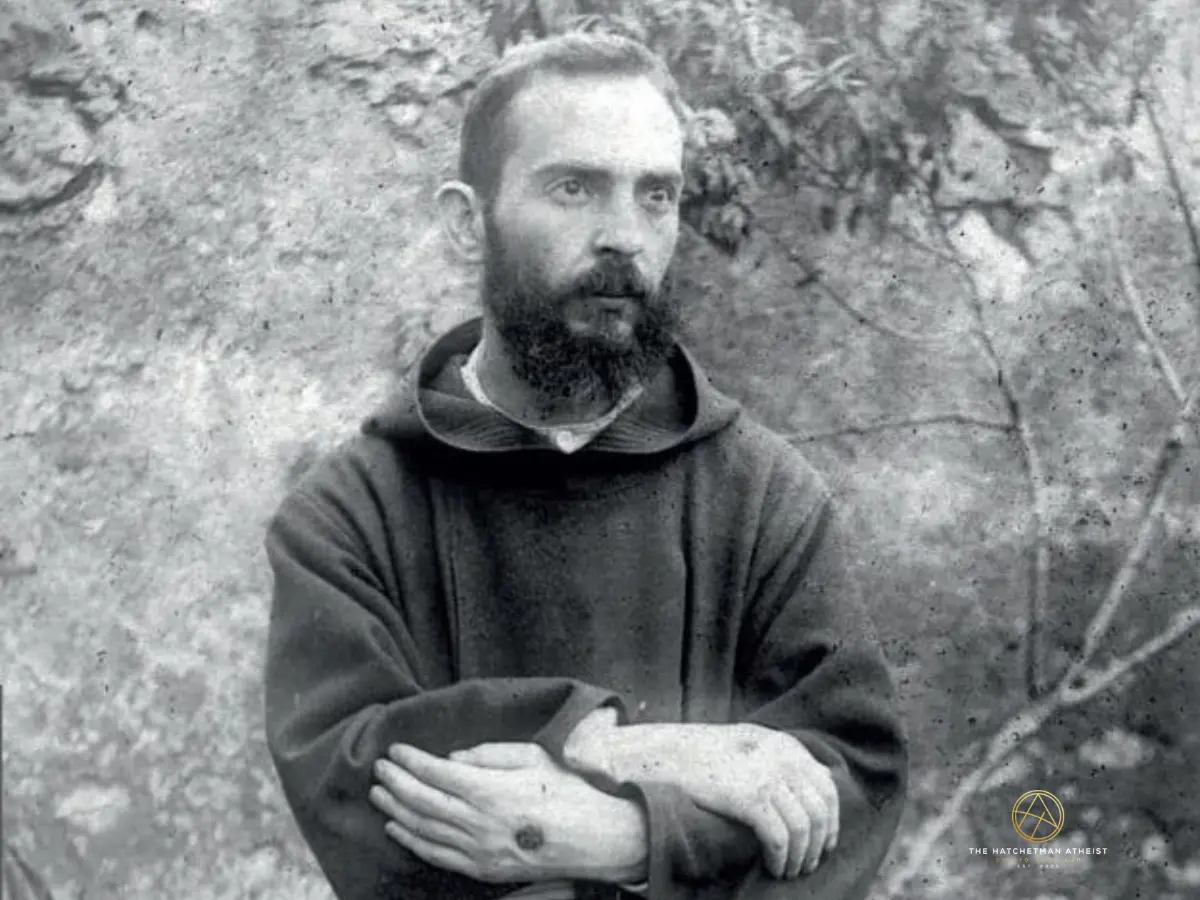

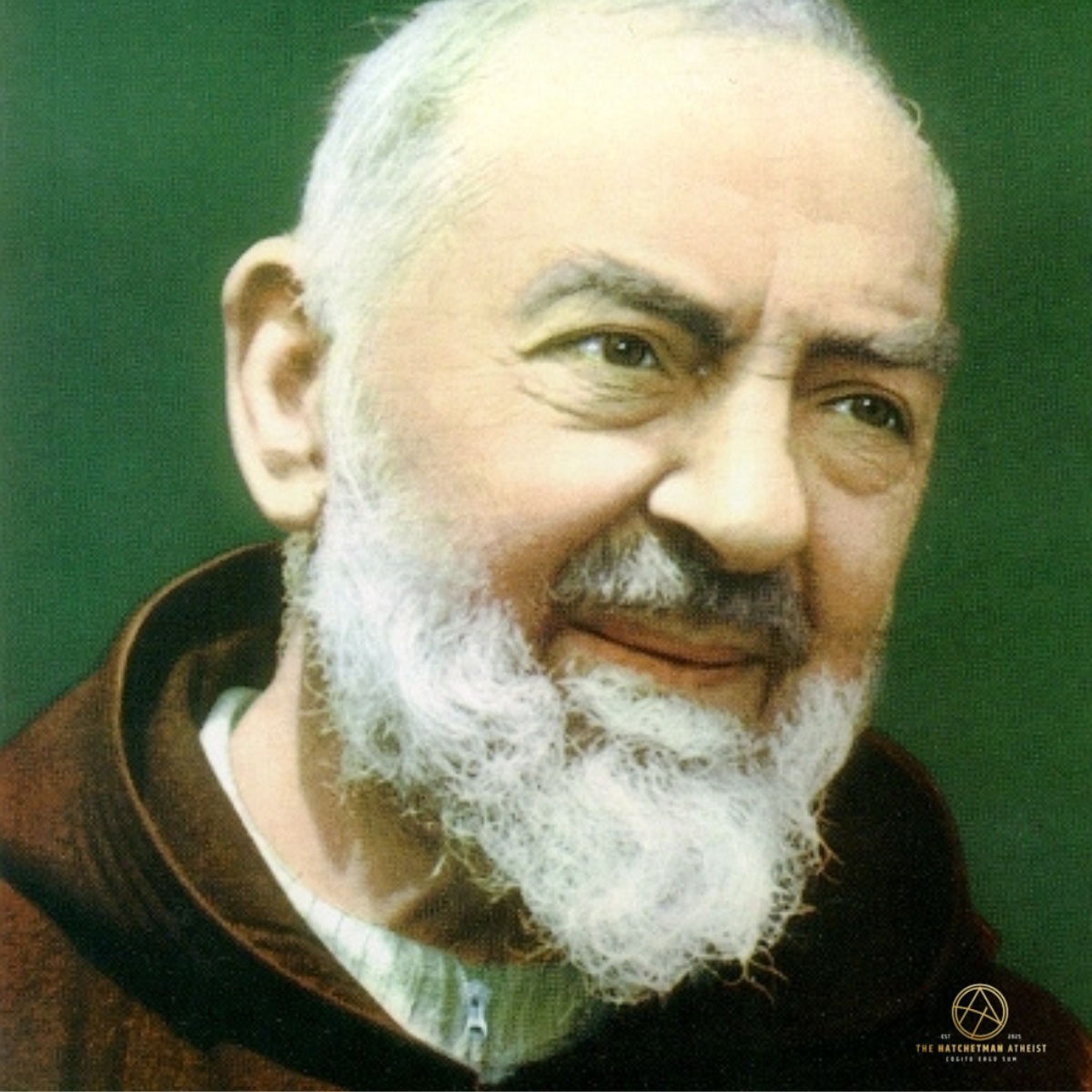

In the pantheon of 20th-century Catholic mystics, few figures loom as large as Padre Pio. Born Francesco Forgione in 1887, this Capuchin friar rose to global fame for allegedly bearing the stigmata—the miraculous wounds of Christ. The faithful saw him as a living saint. The Church canonized him in 2002. But behind the incense and adoration lies a trail of skepticism, contradictory testimonies, and some very curious chemical evidence.

Was Padre Pio a divine vessel—or a devout deceiver?

Let’s take a scalpel to the story.

The Wounds That Wouldn't Heal

According to hagiographies, the stigmata first appeared in 1918 while Pio was praying before a crucifix. Blood seeped from his hands, feet, and side, mimicking the wounds of Christ. These injuries persisted for decades, reportedly never becoming infected, never healing, and never emitting foul odors.

Miraculous? Perhaps. But not unprecedented.

Dozens of Catholic mystics have claimed similar wounds, especially after the 13th century when St. Francis of Assisi became the first reported stigmatic. What sets Pio apart is the sheer scale of attention—and the intense pushback from within his own Church.

The Vatican's Red Flags

Not everyone was convinced.

Between 1920 and 1931, several Vatican-appointed medical investigators examined Pio’s wounds. Their verdicts were damning. One doctor, Amico Bignami, concluded in 1919 that the lesions were artificially maintained using a caustic substance—likely phenol. Another, Giuseppe Sala, described the wounds as superficial and suspiciously uniform. He too suspected chemical irritation.

In 1923, the Holy Office issued a statement: “The Supreme Sacred Congregation declares that no supernatural character can be attributed to the facts relative to the stigmata of Padre Pio.”

This was not a fringe opinion. Even Pope John XXIII reportedly called Pio “a straw idol” and accused his supporters of fostering a cult of personality.

So what changed?

Politics, Not Proof

In the postwar years, public devotion to Pio surged. Pilgrimages, donations, and ecstatic testimonials flooded the Vatican. Politically, silencing such a beloved figure became untenable. Restrictions were lifted. Pio’s fame soared.

By the 1960s, skepticism had receded into whispers. By 2002, it was buried under canonization rites.

But the original doubts never disappeared. They were merely archived.

Chemical Clues?

Let’s talk phenol.

Phenol is a corrosive compound with disinfectant properties. It was widely available in the early 20th century, especially in hospitals and among clergy who administered last rites. Pio reportedly had access to it for “sterilizing hypodermic needles.” The problem? There’s no record of him performing any medical procedures—certainly nothing that would involve a syringe. He wasn’t a nurse. He wasn’t administering injections.

So why was he regularly requesting a caustic agent capable of producing precisely the type of burns he displayed?

It was Father Agostino Gemelli, a Franciscan friar and physician, who first raised this issue publicly. After being denied access to examine Pio directly, Gemelli reviewed the available data and concluded that the wounds were self-inflicted—probably with phenol. Others followed suit. Dr. Giorgio Festa, a physician sympathetic to Pio, still noted the use of antiseptics and unusual wound behavior. Dr. Giuseppe Sala was even more direct: the injuries looked artificial.

Even Cardinal Carlo Raffaele Rossi, who led a secret Vatican inquiry in 1921, found the stigmata questionable. While he praised Pio’s piety, he found no supernatural cause for the wounds and hinted at psychological explanations.

Miracle or Medical Mystery?

A consistent trait of Pio’s wounds was their resistance to healing. They stayed fresh. Open. Bleeding. Yet they never became infected—despite pre-antibiotic hygiene. This isn’t just uncommon. It’s biologically implausible.

Dr. Bignami’s conclusion? Phenol was likely applied intermittently to prevent scabbing and simulate a supernatural permanence.

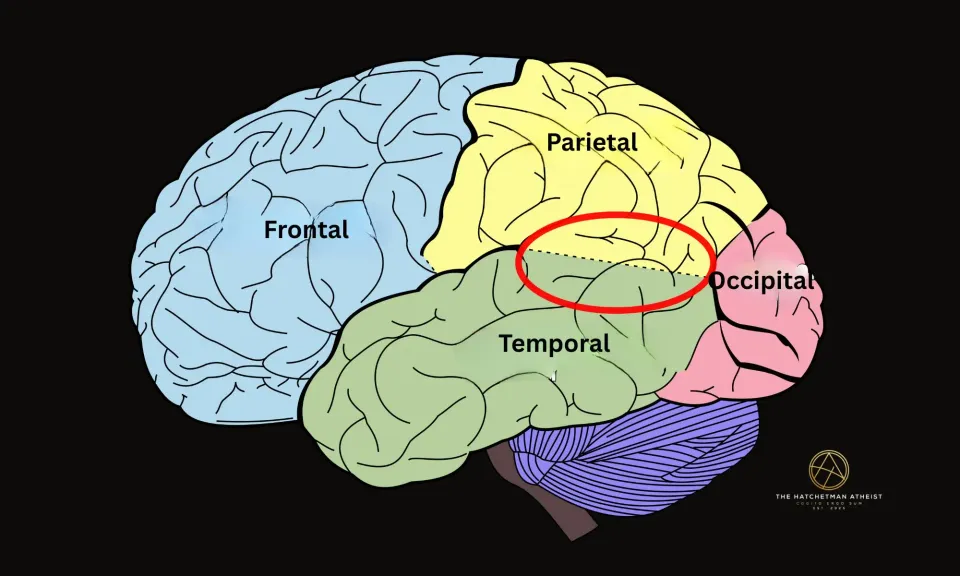

Add to this Pio’s long history of religious ecstasies, visions, and psychosomatic illnesses, and you have a profile not just of a saint, but of someone who may have deeply internalized the desire to suffer like Christ.

Witnesses in the Dark

Supporters point to testimonials from those close to Pio. Some friars claimed to have seen him levitate or bilocate. Visitors described the scent of violets in his presence. Many insisted the stigmata were genuine.

But eyewitness testimony is unreliable—especially in religious settings charged with expectation and reverence. And when the Church finally permitted partial medical examinations, they were constrained by Pio’s modesty and the reverence of his handlers.

We have no independent, full clinical report from a neutral examiner.

What we do have are contradictions, cautious medical notes, and heavy Vatican editing.

Final Thoughts

Padre Pio’s life was marked by illness, visions, and intense bouts of spiritual drama. From an early age, he suffered mysterious ailments that defied diagnosis, often retreating into trances that his fellow friars sometimes mistook for signs of holiness. But spiritual rapture and psychological instability can look uncomfortably similar.

Meanwhile, the physical evidence raises its own set of questions—sharp ones. Phenol doesn’t appear on the skin by accident. Doctors and Church investigators alike reported wounds that were suspiciously clean, symmetrical, and unnaturally persistent. They didn’t scab, they didn’t heal, and they bore the telltale signs of chemical maintenance.

Yes, the Church canonized him. But canonization is a political process, not a scientific one. The Church had every reason to protect its mystique—and no obligation to satisfy skeptical inquiry.

But we do.

The Church may prefer ambiguity. I don’t. Given the red flags, I see not divine suffering, but deliberate fabrication.

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so on patreon.

Works Cited

Bruschi, Arnaldo. Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. Rome: Lateran University Press, 2004.

Cavallaro, Maria. “The Medical Controversy Surrounding Padre Pio’s Stigmata.” Journal of Religious Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, 2010, pp. 211–228.

Festa, Giorgio. The Truth About Padre Pio’s Stigmata. Translated by Lucia Manetti, Edizioni San Michele, 1938.

Gemelli, Agostino. “Relazione Medica sul Caso di Padre Pio.” Vatican Secret Archives, 1920.

Luzzatto, Sergio. Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. Translated by Frederika Randall, Metropolitan Books, 2010.

Rossi, Carlo Raffaele. Secret Vatican Report on Padre Pio, 1921. Vatican Archives.

Sala, Giuseppe. “Osservazioni Cliniche sulle Piaghe di Padre Pio.” Archivio Medico Italiano, vol. 17, no. 4, 1923.