Was Christmas Stolen from Pagans? The Real History Behind December 25

Was December 25th actually stolen from Sol Invictus and Saturnalia? Discover why the date of Christmas was born from complex Christian arithmetic and the "Equinox + 9 months" rule rather than a Roman hijacking.

TL;DR

- The Myth: Christians "baptized" the Roman winter solstice (Sol Invictus) to make conversion easier.

- The Reality: December 25th was calculated by early church chronologists like Sextus Julius Africanus and Hippolytus decades before the Sol Invictus festival was even established.

- The Math: It began with the Spring Equinox (March 25)—the traditional date for the creation of the world and the conception of Jesus.

- The Result: By adding a perfect 9-month gestation to March 25, Christians arrived at December 25 as a mathematical and theological conclusion, not a borrowed one.

- The Solar Twist: Solar imagery (Jesus as the "Sun of Righteousness") was added after the date was already fixed to explain its symbolic meaning.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What the evidence can—and can’t—do

- Step one: the idea that sacred lives are “complete”

- Step two: Sextus Julius Africanus—and what he actually argued

- Step three: De Pascha Computus and Christian math without pagan help

- Step four: Hippolytus and counting forward

- A necessary detour: why January 6 existed

- When December 25 shows up on the calendar

- Solar imagery: meaning added after the fact

- So what actually happened?

- Footnotes

- Works cited

Introduction

Most people think the date of Christmas came from pagans celebrating the winter solstice. It sounds tidy, dramatic, and vaguely rebellious—exactly the kind of explanation that spreads well online. The problem is that when you actually follow the historical trail, that story starts to wobble.[1]

This article explains how December 25 came to be associated with Jesus’s birth by walking through the actual arguments Christians made, in the order they made them. No solstice shortcuts, no borrowed festivals required. Solar symbolism does show up later—but that turns out to be commentary, not the original math.[2]

What the evidence can—and can’t—do

No early Christian source gives us a birth certificate for Jesus. The gospels don’t offer a calendar date, and no second-century writer says, plainly and unambiguously, “Jesus was born on December 25.”[3]

What we do have, starting in the late second and early third centuries, is something else entirely: Christians who loved timelines. They tried to line up creation, incarnation, death, and resurrection into a single, elegant historical framework. December 25 comes out of that effort—not as a memory, but as a conclusion.[4]

That difference matters.

Related skeptical posts

Step one: the idea that sacred lives are “complete”

The whole calculation process rests on a simple assumption that shows up repeatedly in late antiquity: the lives of important, God-chosen figures are symmetrical. They begin and end on the same day.[5]

A Jewish example often cited is Moses. The Babylonian Talmud says Moses died on the same date he was born, the seventh of Adar. That doesn’t mean every Jewish thinker believed this, or that it goes back to the time of Moses himself. What it does show is that ancient interpreters were comfortable shaping sacred biography into a tidy numerical pattern.[6]

Christians picked up the same instinct—but with a twist.

Instead of matching Jesus’s birth and death, they increasingly matched his conception and his death. The reasoning went like this: if Jesus was the perfect, divinely ordered life, then the moment he entered the world and the moment he redeemed it should fall on the same calendar day.[7]

Augustine states this idea outright centuries later: “He is believed to have been conceived on the 25th of March, upon which day also He suffered.”[8] That sentence is doing a lot of work. Once the conception date is fixed, the birth date becomes a simple matter of counting months.

This symmetry is not something modern historians invented. Ancient writers say it themselves.

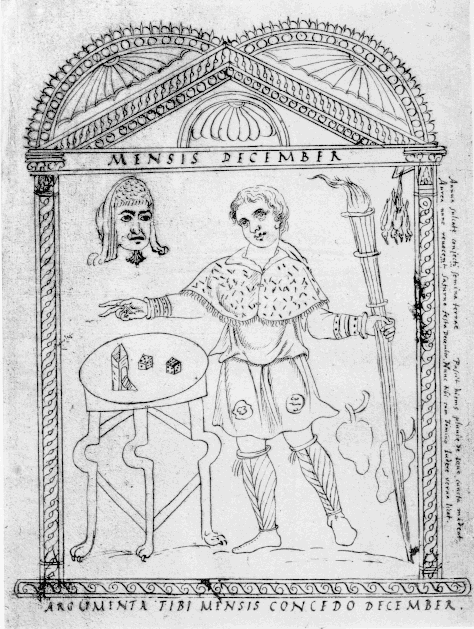

Calendar material from the Chronography of 354—context for how late antique lists recorded sacred and civic dates.

Step two: Sextus Julius Africanus—and what he actually argued

Sextus Julius Africanus was writing in the early third century, and almost everything he wrote survives only in fragments quoted by later authors. He was obsessed with chronology—lining up biblical events with Greek and Roman history to make the whole thing hang together.[9]

Africanus is often dragged into Christmas debates, usually as the alleged mastermind behind December 25. That reputation doesn’t survive contact with the evidence.

What Africanus actually seems to have argued for is a March 25 incarnation or conception date, tied into a much larger scheme about creation and redemption. He does not give a birth date for Jesus. Not December 25. Not any other date either.[10]

This matters because one popular criticism claims Africanus “started with December 25 and reasoned backward.” That accusation fails immediately. You cannot reason backward from a conclusion you never state.

The fair conclusion is more modest: Africanus helped make March 25 an attractive anchor point. Later Christians noticed that if conception happened on March 25, then a birth nine months later lands neatly in late December. Africanus provided part of the scaffolding, not the finished building.[11]

Illustration from the Chronography of 354, a compilation that preserves the earliest unambiguous Roman calendar entry for December 25 as Christ’s birth.

Step three: De Pascha Computus and Christian math without pagan help

Around the year 243, an anonymous Latin writer produced a work called De Pascha Computus. Its main goal was to calculate the date of Easter, but along the way it reveals how Christian thinkers were reasoning about time.[12]

The author argues that creation began on March 25 and then lines up the days of creation with theological meaning. Since the sun and moon were created on the fourth day, Christ—the true light—belongs there symbolically. That leads the author to propose March 28 as Jesus’s birth date.[13]

March 28 didn’t win out, but that’s not the point.

The important thing is how the argument works. It uses creation theology, symbolism, and arithmetic. There’s no appeal to solstices. No pagan festivals. No sense that the author feels the need to outdo Roman religion. This is Christian date-making in its natural habitat.[14]

Step four: Hippolytus and counting forward

Hippolytus of Rome, another early third-century figure, adds a further piece to the puzzle. His writings survive unevenly, and scholars still debate exactly how his chronological ideas fit together. But a strong modern case has been made that Hippolytus placed Jesus’s conception around Passover season and then counted forward to arrive at a December 25 birth.[15]

This does not mean Christmas was widely celebrated in his lifetime. It means the calculation itself existed as a plausible conclusion before the mid-fourth century.

Again, the direction of reasoning is consistent: passion first, conception aligned with it, birth derived afterward.

Early Christian “Good Shepherd” imagery—useful as a reminder that later Christian symbolism often flourished after key dates were already established.

A necessary detour: why January 6 existed

If December 25 was such a good answer, why didn’t everyone use it?

In parts of the eastern Christian world, January 6 functioned as a celebration of Jesus’s birth, baptism, or public manifestation. Different communities emphasized different moments. Early Christianity was far less uniform than later tradition often assumes.[16]

December 25 spread gradually eastward in the late fourth century, not because someone discovered new evidence, but because liturgical priorities shifted. Understanding this helps prevent the mistake of treating Rome’s calendar as the whole Christian world.

When December 25 shows up on the calendar

The first clear, hard evidence for December 25 as Jesus’s birth date comes from a Roman calendar list preserved in the Chronography of 354. The entry reads: “VIII kal. Ian. natus Christus in Betleem Iudeae.” That translates to “On the eighth day before the Kalends of January, Christ was born in Bethlehem of Judea.”[17]

At this point, December 25 stops being a theory and starts being a date on paper.

But even then, it doesn’t instantly become universal. Christmas as a major feast, and later as a season, develops over time through preaching, imperial involvement, and church councils. “Official” turns out to be a slow process.[18]

Solar imagery: meaning added after the fact

Eventually, Christians began explaining Christmas using solar language. Christ becomes light in the darkness. His birth aligns with the turning of the year. Later texts even match conceptions to equinoxes and births to solstices.[19]

That symbolism is real—but it comes after the date is already in place.

In other words, solar imagery explains how Christians talked about December 25 once they had it. It does not explain how they arrived there in the first place. Treating symbolism as causation gets the timeline backward.

So what actually happened?

December 25 wasn’t chosen because someone noticed a pagan holiday and decided to hijack it. It emerged because Christian thinkers were trying to make sacred history line up neatly—creation, incarnation, and redemption folded into a single calendar logic.[20]

Later overlap with solar language and Roman culture is undeniable, but it belongs to a later stage. The original engine was Christian arithmetic, not religious competition.

Understanding that difference is what separates history from a good meme.

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so here.

Works cited

Augustine. De Trinitate. Quoted in “The Date of the First Good Friday.” Association of Catholic Priests, 26 Mar. 2016, associationofcatholicpriests.ie/the-date-of-the-first-good-friday/.

Babylonian Talmud. Kiddushin 38a. Sefaria, www.sefaria.org/Kiddushin.38a.

Bradshaw, Paul F. “The Dating of Christmas: The Early Church.” The Oxford Handbook of Christmas, Oxford UP, 2020.

Chronography of 354. “Depositio Martyrum.” Tertullian.org, www.tertullian.org/fathers/chronography_of_354_12_depositions_martyrs.htm.

Nothaft, C. P. E. “The Origins of the Christmas Date: Some Recent Trends in Historical Research.” Church History, vol. 81, no. 4, 2012, pp. 903–911.

Pearse, Roger, editor. De Pascha Computus. 2022 PDF edition.

---. De Solstitiis et Aequinoctiis: On the Solstices and the Equinoxes. 2022 PDF edition.

C. P. E. Nothaft, “The Origins of the Christmas Date: Some Recent Trends in Historical Research,” Church History 81, no. 4 (2012): 903–904. ↩︎

Paul F. Bradshaw, “The Dating of Christmas: The Early Church,” in The Oxford Handbook of Christmas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). ↩︎

Bradshaw, “The Dating of Christmas.” ↩︎

Nothaft, “Origins of the Christmas Date,” 904–906. ↩︎

Thomas C. Schmidt, “Calculating December 25 as the Birth of Jesus in Hippolytus’ Canon and Chronicon,” Vigiliae Christianae 69 (2015): 545–547. ↩︎

Babylonian Talmud, Kiddushin 38a. ↩︎

Schmidt, “Calculating December 25,” 548–549. ↩︎

Augustine, De Trinitate, quoted in “The Date of the First Good Friday.” ↩︎

Bradshaw, “The Dating of Christmas.” ↩︎

Nothaft, “Origins of the Christmas Date,” 907. ↩︎

Nothaft, “Origins of the Christmas Date,” 908–909. ↩︎

De Pascha Computus, ed. Roger Pearse. ↩︎

Pearse, De Pascha Computus. ↩︎

Bradshaw, “The Dating of Christmas.” ↩︎

Schmidt, “Calculating December 25,” 552–558. ↩︎

Bradshaw, “The Dating of Christmas.” ↩︎

Chronography of 354, “Depositio Martyrum.” ↩︎

Bradshaw, “The Dating of Christmas.” ↩︎

Pearse, De Solstitiis et Aequinoctiis. ↩︎

Nothaft, “Origins of the Christmas Date,” 910–911. ↩︎