How Revival Preachers and Hypnotists Hijack Your Memory

Memory isn’t a recording—it’s a rewrite. From revivals to hypnosis to courtroom drama, we explore how suggestion and emotion inflate our memories into false certainties that feel undeniably real.

TL;DR:

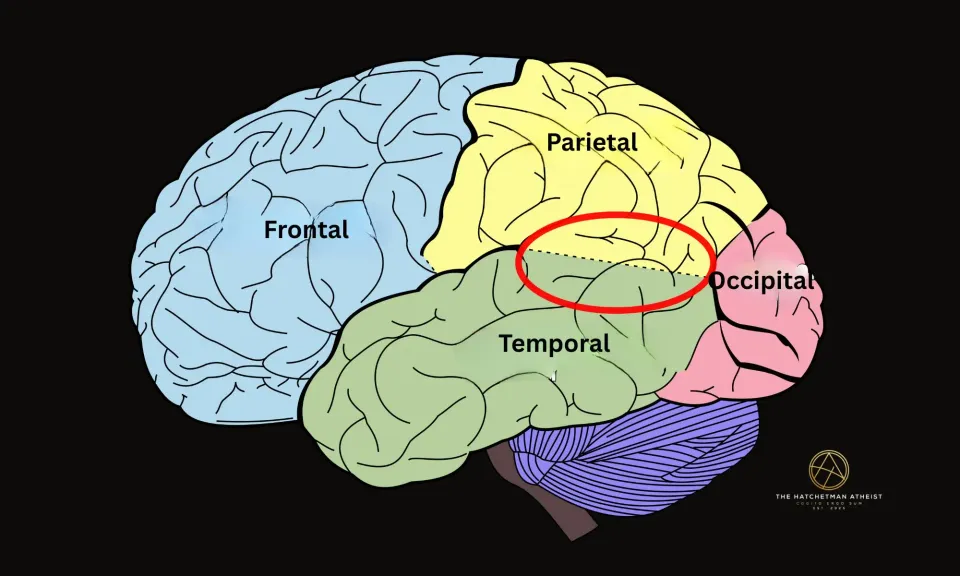

Our brains don’t record—they rewrite. Memory inflation is the brain’s way of turning a faint impression into a vivid narrative—sometimes accurate, often not. When emotion and authority enter the picture, memories don't just evolve—they inflate.

What Is Memory Inflation?

Memory inflation isn’t a glitch. It’s the brain doing what it does best: storytelling. It’s the process by which minor impressions or half-formed recollections blossom into full-blown memories. All it takes is a bit of emotional charge, a dose of repetition, and a nudge from someone in a position of influence. Over time, the fuzzy stuff sharpens. That uncertain glance becomes a dramatic moment. That hazy feeling turns into a life-defining episode.

(Loftus and Ketcham 72).

Flashbulb Memories: High Definition, Low Accuracy

When something shocking happens, we swear we’ll never forget where we were. And we usually don’t. But what we do forget is the accuracy of the details. After the Challenger explosion in 1986, Ulric Neisser and Nicole Harsch asked students to describe how they heard the news. Almost three years later, most gave wildly different versions—despite being absolutely sure they were right.

"Confidence, not accuracy, characterizes flashbulb memories. People believe them deeply even when they are demonstrably wrong" (Neisser and Harsch 294).

The same thing happened after 9/11. People “remembered” things in perfect detail that just didn’t happen. The stories were heartfelt. They just weren’t true. Emotion doesn’t make memory better—it makes it bolder.

The “Lost in the Mall” Experiment: Fiction Becomes Memory

Elizabeth Loftus ran an experiment where people were asked to remember several childhood events. One was fake: being lost in a shopping mall and rescued by a kind stranger. Not only did about 25% of participants come to believe it had really happened—they added details. They described the stranger’s clothes. The feeling of panic. The smell of the mall.

"The mind can create vivid, emotionally resonant memories of things that never happened, especially when a trusted authority figure implies that they did" (Loftus and Ketcham 72).

The participants weren’t lying. Their brains were just being helpful—filling in gaps with what seemed likely.

Recovered Memories and the Hypnotist’s Role

In the late 20th century, “recovered memory therapy” exploded in popularity. People who had no memory of childhood trauma suddenly remembered satanic rituals, cult abuse, or long-forgotten assaults—usually under hypnosis or guided visualization. Many of these memories unraveled under investigation.

Loftus and others pointed out that these therapists weren’t intentionally planting lies. They were just good at suggesting, and the brain did the rest. "People can be led to believe with great certainty that they experienced entirely fictional events... and once those memories are established, they’re incredibly difficult to challenge" (Loftus and Ketcham 74).

Alien Abductions: Narrative by Hypnosis

Sleep paralysis. Weird dreams. A feeling that something wasn’t quite right. These are the seeds from which entire alien abduction stories grew. Hypnosis came along and fertilized the ground. Suddenly, abductees had stories: medical experiments, blinking lights, hybrid children.

Susan Clancy studied dozens of these cases and found no evidence of mental illness—just a perfect storm of cultural narrative, personal stress, and hypnotic suggestion. "The memories are sincerely believed," she writes, "but likely the product of suggestion layered on real but misunderstood experiences" (Clancy 82).

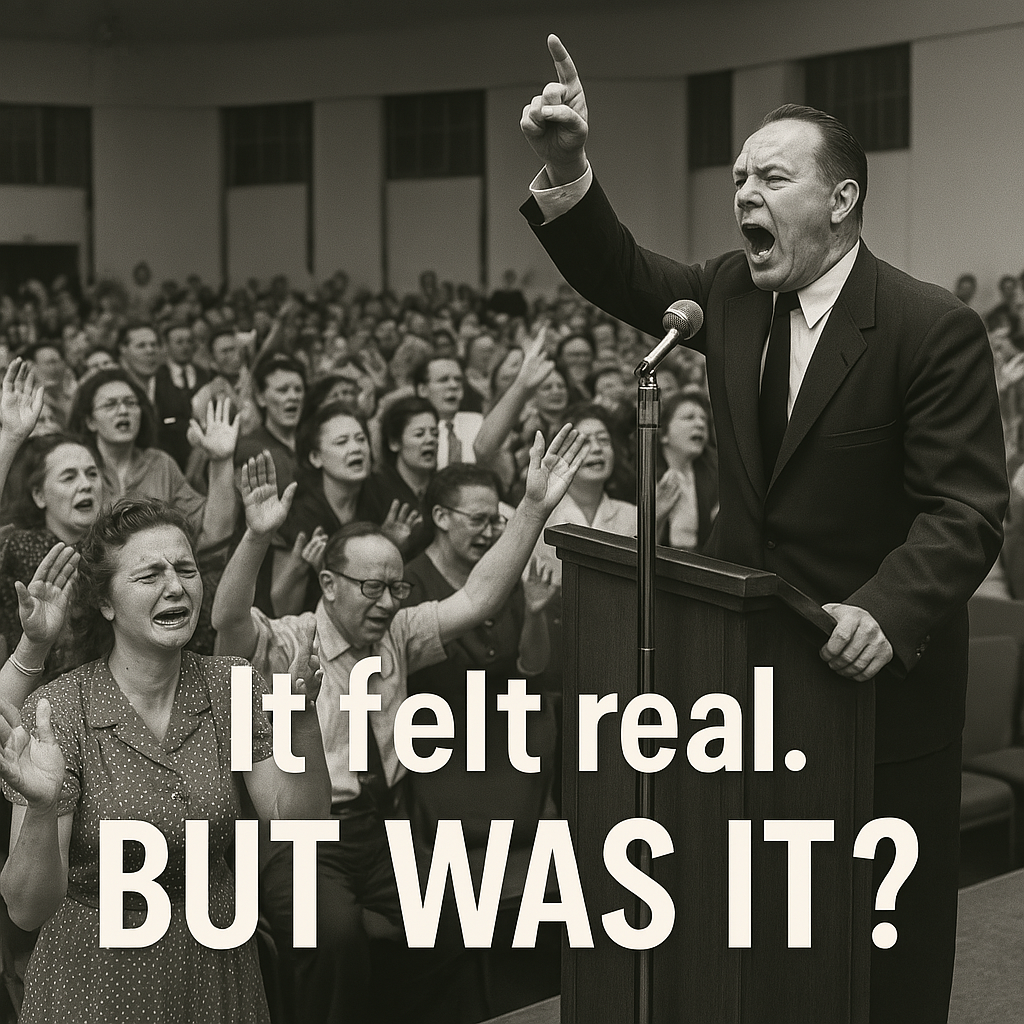

Religious Revivals and Mass Memory Distortion

Revival services—especially in charismatic or Pentecostal circles—are emotional pressure cookers. The lights, the music, the tears, the shouting—it’s an atmosphere engineered for spiritual encounter. And that’s where memory gets bendy.

Take the “Toronto Blessing.” Attendees were told to expect miracles: laughing fits, visions, fainting under the Spirit’s power. And many reported exactly that. But follow-up interviews revealed something odd: people didn’t remember the events clearly until after they heard others talk about them.

"You start to doubt what you saw, and instead remember what you were told you saw" (The Laughing Revival, BBC 1995).

At the Brownsville Revival, worshippers gave public testimonies about healings and visions. Later, some watched video footage and realized their memories didn’t match what actually happened. "It felt real. It was real, to me. But then I watched the tape, and none of that happened the way I remember" (Miller 204).

And then there were the claims of satanic abuse, often “recovered” during high-emotion prayer services. According to Hicks, "Religious authority figures acted as memory facilitators, creating conditions identical to those found in suggestive therapy or hypnosis" (Hicks 112).

Legal Implications: Memory, Justice, and Contamination

The courtroom doesn’t deal in feelings—it deals in facts. And inflated memories can ruin lives. In State v. Michaels (1994), a preschool teacher was convicted based on testimony from children who’d been questioned using leading, repetitive methods. The conviction was later thrown out, but the damage was done.

By the late 1990s, police departments were forced to evolve. Protocols now emphasize:

- Asking only open-ended questions

- Avoiding repetition and suggestion

- Recording all interviews

- Using trained child interviewers

Therapists who used suggestion-heavy methods to “recover” memories faced lawsuits, ethics complaints, and disciplinary action. When memory becomes evidence, its flaws become everybody’s problem.

Conclusion: The Cost of Remembering Wrong

Memory inflation is part of what makes us human. We want our stories to mean something. So we revise, reshape, and re-remember them until they do. But when these stories spill into the therapist’s office, the altar call, or the witness stand, the results can be catastrophic.

False memories don’t feel false. That’s the problem. They arrive with conviction. And conviction, more than anything, sells the story—even when the facts were never there.

Works Cited

Clancy, Susan A. Abducted: How People Come to Believe They Were Kidnapped by Aliens. Harvard UP, 2005.

Hicks, Robert D. In Pursuit of Satan: The Police and the Occult. Prometheus Books, 1991.

Loftus, Elizabeth, and Katherine Ketcham. The Myth of Repressed Memory: False Memories and Allegations of Sexual Abuse. St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

Miller, Stephen. The Pensacola Outpouring: Voices from the Revival. Destiny Image, 2001.

Neisser, Ulric, and Nicole Harsch. "Phantom Flashbulbs: False Recollections of Hearing the News About Challenger." Memory and Cognition, vol. 19, no. 4, 1992, pp. 387–395.

State v. Michaels, 136 N.J. 299 (1994).

Tanner, Lindsey. "Recovered Memory Therapy Leads to False Accusations, Ruined Lives." Associated Press, 29 Mar. 1995.

The Laughing Revival. Directed by Malcolm Brinkworth, BBC, 1995.