Why are we here in this world? What is the purpose? Are we living for our purpose?

If there’s no god, is there still purpose? Yes—but you have to make it. Camus called it rebellion: living fully in a universe that offers no meaning. Like Sisyphus or a dying Viking with his sword, meaning is found not in destiny—but in defiance.

This question gets asked often—usually by theists who’ve been taught that their lives revolve around an ambiguous mission to “serve God.” The idea that people might still find purpose without divine supervision seems genuinely baffling to them. And I get it. When you've been trained to see your worth only through the lens of obedience, it's hard to grasp what real intellectual freedom looks like. It's a short-circuit in the wiring.

But really, it’s not that complicated. “Purpose” exists on two levels.

The first is biological: we are here because we are the product of evolution. Our genetic imperative, so to speak, is to survive and reproduce. That’s the blunt, unsentimental truth about why life continues—genes seeking copies of themselves.

But most people are asking something deeper than DNA. They want existential meaning. This is where Albert Camus’ philosophy of the absurd becomes especially useful.

Camus argued that we live in tension between our desire for meaning and a universe that offers none. This clash—between a mind that craves purpose and a world that gives none—is what he calls the absurd (Camus, Myth 28). Religion and nihilism both try to resolve this. One reaches for false hope; the other gives up. Camus rejects both and proposes something far more daring: revolt. Live fully, love passionately, think clearly—do all of it knowing none of it will last. There is no ultimate meaning, so we must create our own.

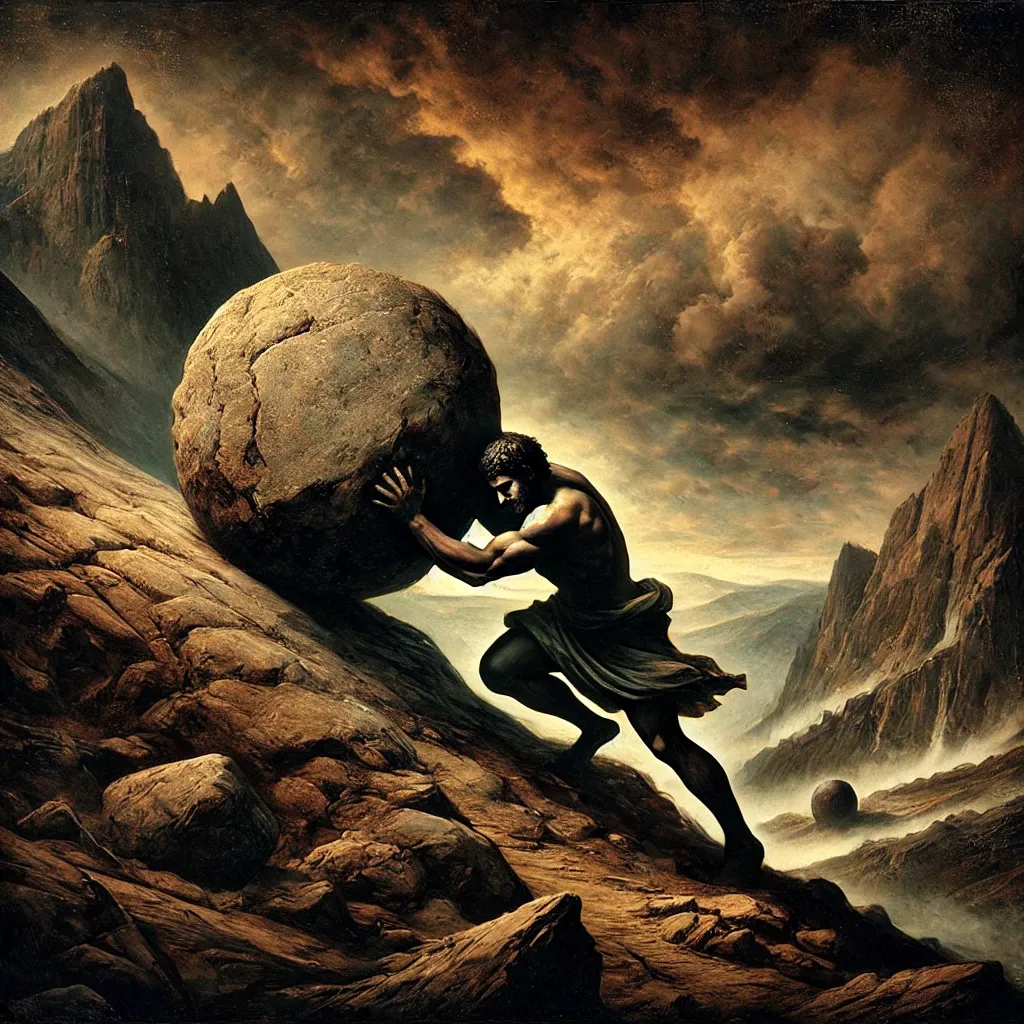

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus compares our condition to Sisyphus, endlessly rolling a rock up a hill. Yet Camus famously insists, “One must imagine Sisyphus happy” (Camus, Myth 123). Why? Because he owns his struggle. He knows it’s futile and chooses to persist anyway.

Camus goes even further in his notebooks, suggesting that true freedom only comes through embracing our mortality: “The only liberty possible is liberty as regards death. The really free man is the one who, accepting death as it is, at the same time accepts its consequences” (Camus, Notebooks).

When I think of this rebellion, I picture a frail old man, bent with age, shaking his fist at the storm—not because he thinks he can stop it, but because he refuses to kneel before it.

Another image I’ve carried with me for years comes from an old Kirk Douglas film, The Vikings. I barely remember the plot, but one scene stuck with me. Douglas’ character, mortally wounded, reaches for his sword as he lays dying. A companion places it in his hands. He rises one last time, sword raised defiantly, before collapsing in death. He had to die on his feet, sword in hand.

That’s how I see meaning. We give life its purpose by how we choose to live it. Some pursue pleasure, others knowledge, some seek transcendence, and many blend all three. Whatever your path, your purpose is the one you create. That, in the face of a silent universe, is the only real rebellion.