Kitzmiller v. Dover, Part Two: Pandas, Proponentsists, and the Find-and-Replace Fail Heard ’Round the Courtroom

The Dover trial exposed intelligent design as creationism in disguise—and one hilarious typo told the whole story. Dr. Barbara Forrest’s testimony traced the edits in Of Pandas and People, and the courtroom caught a movement mid-transformation.

TL;DR: Intelligent design's flagship textbook wasn’t rewritten—it was reworded. And somewhere in that sloppy rebranding sprint, it tripped over its own terminology, leaving behind a typo that might as well have been a confession.

The Book That Started It All

The intelligent design movement didn’t just wake up in a courtroom one day—it arrived gripping a textbook like a holy relic and muttering something about academic fairness. That book was Of Pandas and People, the pet project the Dover school board promoted when it pushed for ID to be taught alongside evolution.

From a distance, it looked polished: scientific tone, textbook layout, confident phrasing. But if you zoomed in just a little, the duct tape started to show. Beneath the buzzwords, it was repackaged creationism—just scrubbed and relabeled after the 1987 Edwards v. Aguillard decision made overt religious content a legal liability.

So the authors did what any group caught flat-footed by a Supreme Court ruling might do: they hit “find and replace.”

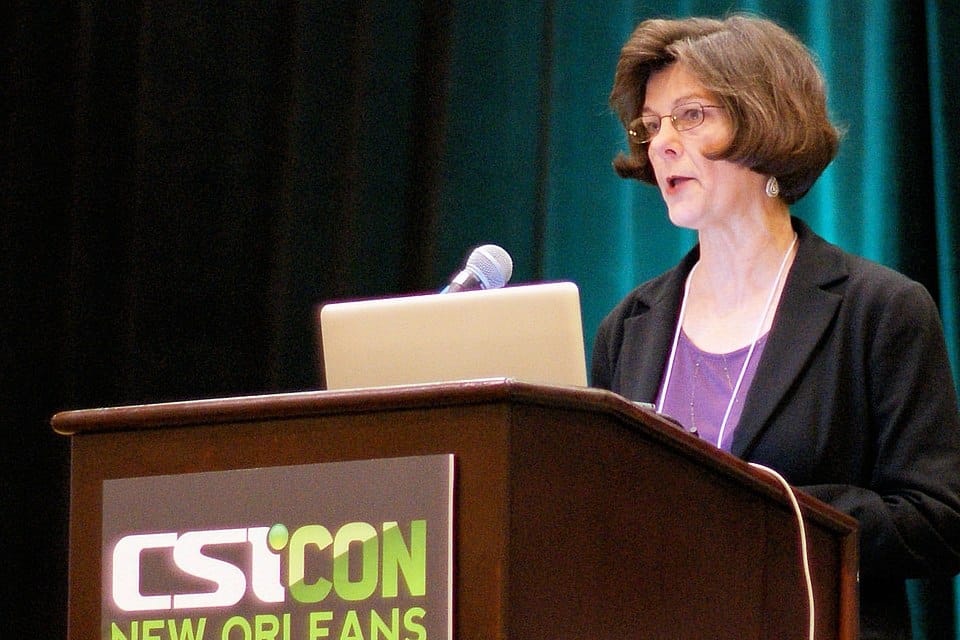

Enter Dr. Barbara Forrest

Dr. Barbara Forrest wasn’t there to speculate. She brought receipts. Calm, focused, and dangerously thorough, she laid out a paper trail that could've doubled as a tutorial on how not to disguise theological intent.

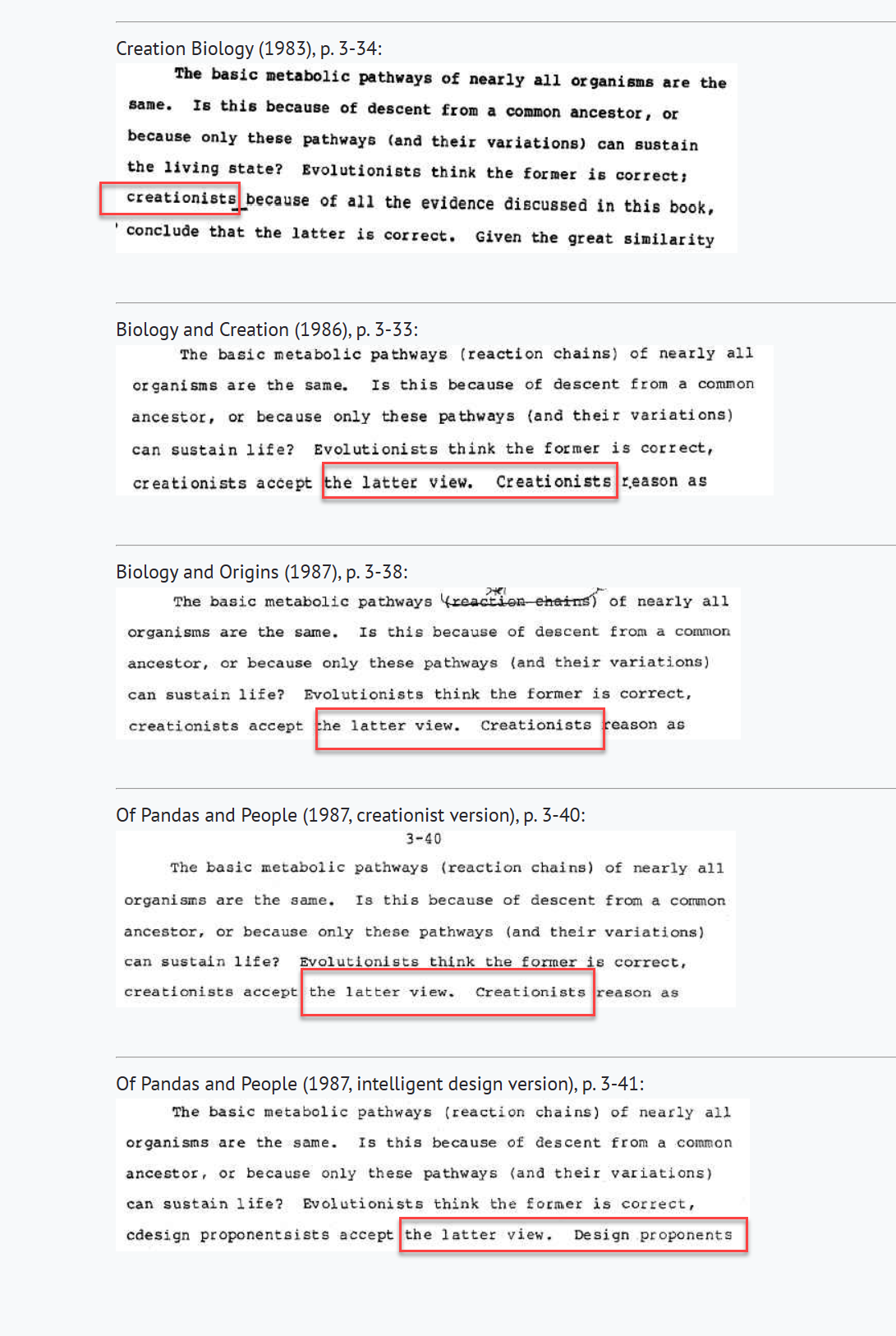

Draft after draft of Of Pandas and People showed a clear pattern: “creationists” morphed into “design proponents,” and “Creator” became “Designer.” Same arguments, different outfit. Like putting Groucho glasses on theology and pretending it was science.

Forrest’s testimony didn’t rely on theatrics—it was built on drafts, dates, and documentation. She didn’t need to interpret the evidence. She just pointed to it and let the court read along.

The Typo That Exposed the Game

And then came the moment. Somewhere in the editorial shuffle, a search-and-replace job didn’t quite finish the job. “Creationists” got partially converted, birthing the now-legendary typo: cdesign proponentsists. Did they really think nobody would notice?

It wasn’t just a mistake. It was a fossil record—proof of transitional terminology frozen mid-evolution. When Forrest unveiled it in court, she didn’t have to make a speech. The word did all the heavy lifting.

Some in the courtroom laughed. Others just stared, blinking at the surreal honesty of the typo. It wasn’t just sloppy—it was telling. It laid bare the entire strategy in one hilariously broken word.

• Kitzmiller Part One: Behe, Biology, and the Tower of Denial

The Court Took Notice

Judge John E. Jones III didn’t miss the significance. In his ruling, he called out the “breathtaking inanity” of the school board’s actions, citing the textual evolution of Pandas as a key piece of the puzzle. The typo, ridiculous as it was, became a courtroom exhibit of intent—proof that intelligent design was less about science and more about legal camouflage.

Forrest’s calm unraveling of the timeline hit harder than any flourish could have. Her testimony drew a direct line from creationism to intelligent design with no detours and no room to wiggle out of it. She didn’t say it. The drafts did.

And it wasn’t just about the book. Forrest highlighted the broader movement—the Discovery Institute’s “Wedge Strategy,” a document that laid out a plan to reintroduce religious values into public institutions under the cover of secular language. Intelligent design wasn’t about discovering new science. It was about slipping old theology in through a side door. It was dumbfounding, in the most forehead-slapping way.

• PBS NOVA – Judgment Day: Intelligent Design on Trial

• NCSE: The “cdesign proponentsists” Smoking Gun

Conclusion: The Typo That Told the Truth

What ultimately sank intelligent design wasn’t just its lack of scientific grounding. It was the visible editorial scars of a rushed rebrand. A movement hoping to pass for science got caught halfway through its costume change.

And nothing captured that better than a single, clunky phrase: cdesign proponentsists. It wasn’t just a typo. It was a confession by keyboard.

Works Cited

Forrest, Barbara, and Paul R. Gross. Creationism's Trojan Horse: The Wedge of Intelligent Design. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Jones, John E. III. Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District. 400 F. Supp. 2d 707 (M.D. Pa. 2005).

Humes, Edward. Monkey Girl: Evolution, Education, Religion, and the Battle for America's Soul. Ecco, 2007.

National Center for Science Education. Kitzmiller v. Dover Trial Documents. https://ncse.