Was Jesus a Myth?: The Failed Apocalyptic Prophet

To understand the historical Jesus, we must discard the modern philosopher and meet the itinerant apocalyptic preacher. When the kingdom didn't arrive, the "retrofit" began.

Jesus, Apocalyptic Failure, and Messianic Retrofit.

Key Takeaway:

Historical evidence suggests Jesus was an apocalyptic preacher who believed the world would end imminently—a prediction that went unfulfilled. To survive this failure, his early followers performed a messianic retrofit, reinterpreting his execution not as a defeat, but as a deliberate, cosmic victory. This shift from historical fact to theological symbol is the foundational fingerprint of the Christian movement.

Table of Contents

- Exile, Crisis, and the Birth of Apocalyptic Hope

- Messiahs, Movements, and Disagreement

- Jesus the Apocalyptic Preacher

- A Messiah Nobody Was Waiting For

- The Temple, Rome, and a Swift End

- Shattered Expectations

- Why This Matters for History

- From Failed Prophet to Timeless Savior: The Logic of Retrofit

To understand the historical Jesus, one has to begin by discarding the modern image of him altogether. The serene moral philosopher, the founder of a global religion, the architect of a church meant to span centuries—none of that belongs to first-century Palestine. Those are retrospective constructions, not starting points.

The world Jesus inhabited was not a calm or unified religious environment. It was volatile, fractured, and saturated with apocalyptic expectation. Judaism in the first century was not a single belief system but a field of competing interpretations, shaped by centuries of conquest, exile, and theological improvisation.

Exile, Crisis, and the Birth of Apocalyptic Hope

The Babylonian Exile was not merely a political catastrophe; it was a theological one. The destruction of Jerusalem and the loss of the Temple forced Jewish thinkers to confront an uncomfortable question: how could a god who had chosen Israel allow his chosen people to be conquered, scattered, and humiliated by foreign empires?

The answers that emerged were not uniform. Some strands of Judaism doubled down on law and tradition. Others moved in a more speculative direction, developing ideas about cosmic justice, resurrection, divine judgment, and an imminent reversal of history itself. These ideas were not part of early Israelite religion in any clear sense; they crystallized under pressure, shaped by contact with Persian and Hellenistic thought and by the trauma of repeated subjugation.

Out of this ferment emerged apocalypticism: the belief that history was approaching a breaking point, that God would soon intervene decisively, overthrow the forces of evil, and reorder the world according to divine justice. This intervention would not unfold gradually. It would be sudden, catastrophic, and final.

This article is part of a four-post series examining Jesus through the lens of historical method rather than theological expectation. Related essays:

Messiahs, Movements, and Disagreement

By the first century, apocalyptic thinking was widespread but not universal. Groups such as the Essenes and many Pharisees expected an imminent end of the age, a resurrection of the dead, and the arrival of a messianic figure—an anointed leader who would act as God’s agent in the coming judgment. Other groups, most notably the Sadducees who controlled the Temple priesthood, rejected these ideas entirely. They denied resurrection, dismissed apocalyptic speculation, and focused on maintaining religious authority within the existing order.

This disagreement matters. It shows that belief in a coming messiah was not a timeless or unanimous Jewish doctrine. It was a contested response to political domination and theological crisis.

The messiah envisioned by apocalyptic Jews was not a suffering redeemer or a spiritual symbol. He was a conquering figure: a prophet-king who would judge the wicked, vindicate the righteous, and elevate the faithful to positions of authority in a newly reordered world. History itself would be brought to a halt and restarted under God’s direct rule.

Jesus the Apocalyptic Preacher

This is the world into which Jesus steps—and it is the only world in which his message makes sense.

Jesus was not an abstract moral teacher delivering timeless wisdom. He was an itinerant apocalyptic preacher, one of many, proclaiming that divine judgment was imminent. His central message was simple and urgent: repent, because the kingdom of God was near. Not distant. Not metaphorical. Near.

Jesus did not invent this message. He inherited it from John the Baptist, whose movement Jesus initially joined. John preached repentance in preparation for coming judgment; Jesus took up the same theme after John’s arrest. This continuity is historically significant. It places Jesus squarely within an existing apocalyptic tradition rather than above or outside it.

Crucially, in the sayings most plausibly attributed to Jesus, he does not proclaim himself as the messiah. Instead, he speaks of another figure—the “Son of Man”—who would soon arrive to judge the world, separate the righteous from the wicked, and inaugurate God’s reign. The urgency of Jesus’ teaching depends on this expectation. The Son of Man could arrive at any moment, like a thief in the night. One had to be ready.

Later Christian theology would reinterpret these sayings as references to Jesus himself, often projecting a second coming back into texts that make far more sense as expectations of a first and imminent arrival. During his ministry, Jesus does not speak of founding a church, establishing a long-term institution, or preparing for centuries of delay. The language of the kingdom is immediate, not programmatic.

A Messiah Nobody Was Waiting For

There are hints in the gospel traditions that some of Jesus’ followers suspected he might be the messiah. But these hints are inconsistent, ambiguous, and often awkwardly presented. That awkwardness is telling. It suggests uncertainty rather than clarity, confusion rather than orchestration.

If Jesus had openly and consistently presented himself as the messiah, later authors would have had no need to hedge, obscure, or retrofit his words. Instead, the texts show signs of theological strain—efforts to reconcile earlier expectations with later beliefs.

This is not what invention looks like. It is what reinterpretation looks like.

The Temple, Rome, and a Swift End

Jesus’ execution does not require a grand conspiracy or religious vendetta to explain it. The historical context does the work on its own.

Passover was a volatile time in Jerusalem. Large crowds gathered, national memory was sharpened, and Roman authorities were on high alert for unrest. Pontius Pilate normally governed from Caesarea, but he brought troops into Jerusalem during festivals precisely to suppress potential uprisings.

Jesus’ disruption in the Temple—whatever its exact form—was a public, symbolic challenge staged at the worst possible moment. It would have attracted attention immediately. From a Roman perspective, the details of Jewish theology were irrelevant. What mattered was order.

Jesus was arrested, tried briefly, and executed as a troublemaker. He died the death Rome reserved for failed insurrectionists and social agitators: public crucifixion, swift and humiliating.

Shattered Expectations

This outcome was not part of the plan.

Apocalyptic preaching only makes sense if the preacher expects history to end imminently. Jesus’ message presupposed divine intervention, judgment, and reversal. Instead, he was killed, the world continued, and nothing changed.

The expectations of his followers were shattered. There was no kingdom. No judgment. No exaltation of the meek. Their leader was dead, executed without honor, discarded like a criminal.

The cry attributed to Jesus on the cross—“My God, my god, why have you forsaken me”—is powerful precisely because it does not sound victorious. It sounds like disorientation. It fits a man whose expectations collapsed under the weight of reality. It fits a failed apocalyptic prophet far better than a divine being calmly executing a predetermined plan.

Why This Matters for History

None of this proves theological claims one way or another. That is not the point.

What it does show is that Jesus, as reconstructed by critical historical methods, looks nothing like a figure invented to succeed. He looks like a real person operating within a specific historical moment, shaped by its ideas, animated by its hopes, and undone by its realities.

Movements built around fictional saviors do not begin with failure. They do not start with embarrassed followers scrambling to reinterpret defeat as victory. They do not preserve memories that complicate later theology.

Those are the fingerprints of history, not myth.

What followed Jesus’ execution was not immediate clarity, but decades of reinterpretation.

From Failed Prophet to Timeless Savior: The Logic of Retrofit

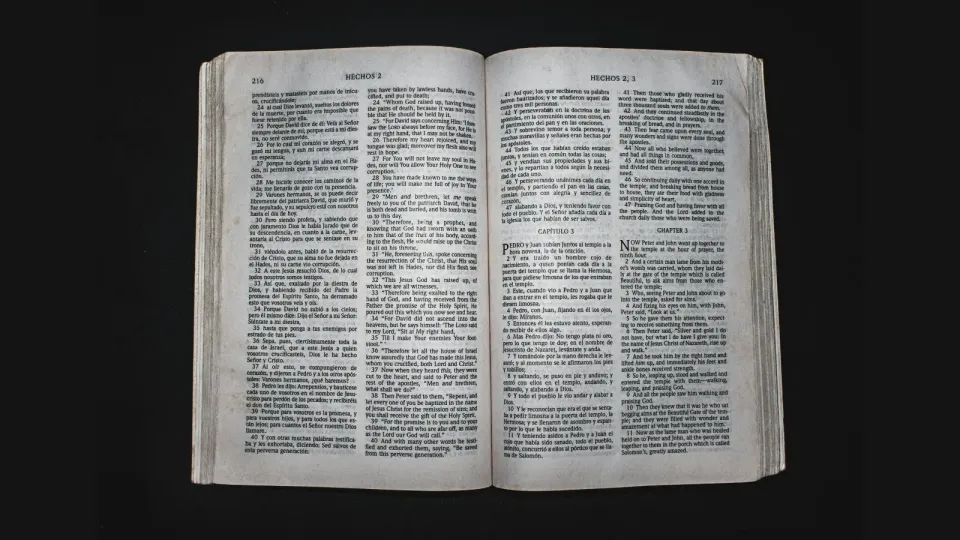

Jesus was almost certainly executed around 30 CE. The first gospel, by most scholarly estimates, was not written until roughly forty years later. That gap matters—not because it undermines the sources, but because it explains their shape.

Forty years is ample time for a movement to form, for memories to circulate orally, for anecdotes to harden into teaching material, and for interpretation to begin doing its quiet work. By the time the gospels were written, Christianity already existed as a living community with practices, beliefs, and theological commitments. The authors were not recording raw events. They were organizing inherited material—some written, much of it oral—into narratives that made sense of what had already happened.

Into this environment steps Paul of Tarsus, whose letters predate the gospels and whose influence on Christian theology is difficult to overstate. Paul was not interested in preserving the details of Jesus’ earthly ministry. His focus was cosmic and theological: a crucified and risen Christ whose death and exaltation reconfigured humanity’s relationship with God. Whatever Jesus had been during his life, Paul reframed him as the centerpiece of a new religious system.

This did not erase earlier traditions. It reinterpreted them.

The gospel writers inherited stories that already circulated among believers—stories that included inconvenient elements: Jesus’ association with John the Baptist, his failure to bring about the kingdom, his execution, his confusion, his despair. These elements could not simply be discarded. They were too well established, too widely known. Instead, they were re-read.

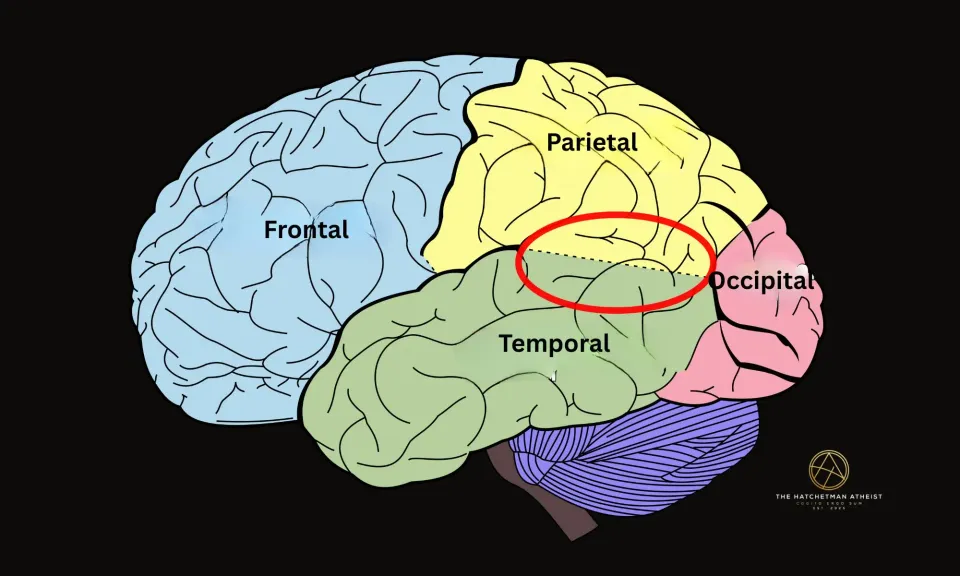

This process is visible in the handling of Jesus’ apocalyptic language. In the sayings most plausibly traced to the earliest layer of tradition, Jesus speaks of the “Son of Man” in the third person—a future figure who would arrive soon to judge the world. That creates a doctrinal problem once Jesus himself becomes identified as the messiah. Why would the messiah speak as though he were waiting for someone else?

The solution was not consistency but reinterpretation. In some passages, Jesus continues to speak of the Son of Man as a coming figure. In others, the language subtly shifts, and Jesus appears to refer to himself using the same title. The result is uneven and sometimes clumsy, but that clumsiness is instructive. It reflects a tradition under stress, trying to reconcile inherited sayings with emerging dogma.

This is what retrofitting looks like in real time. It is not a clean rewrite. It is an attempt to preserve memory while reshaping meaning.

The same dynamic appears elsewhere: failed predictions are reimagined as spiritual insights; imminent judgment becomes deferred fulfillment; an execution meant to end a movement is transformed into the very mechanism of salvation. The figure who expected divine intervention is recast as the intervention itself.

What emerges from this process is not a character invented whole cloth, but a layered figure—one whose original context is still faintly visible beneath later theological paint. Jesus becomes timeless not because he began that way, but because his failure demanded explanation. The movement did not start with a savior who transcended history. It ended up with one.

That transformation—from insignificant apocalyptic preacher to cosmic symbol—does not require fabrication. It requires time, memory, reinterpretation, and a community motivated to find meaning in disappointment.

Those are ordinary historical forces. And they leave ordinary historical fingerprints.