𝐇𝐨𝐰 𝐭𝐨 𝐑𝐞𝐚𝐝 𝐁𝐢𝐛𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐡𝐞𝐜𝐲 𝐖𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐆𝐞𝐭𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐏𝐥𝐚𝐲𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐲 𝐈𝐭

Not every biblical prophecy is a divine mic-drop. Some were written after the fact, others misread poetry as prediction. Here’s how to tell if you're reading inspiration — or just post-production spin.

Not every biblical prophecy is future-telling magic. Some are historical recaps with flair, some are emotional poetry hijacked for theology, and some are just creative license with a holy stamp. Read carefully — or risk getting played.

Biblical prophecy. For some, it's divine foreshadowing that would put Marvel to shame. For others, it's a literary game of smoke and mirrors, full of hindsight predictions and poetic license. Whether you're a believer, a skeptic, or just prophecy-curious, one thing is clear: not all “prophecies” in the Bible are playing the same game.

Some are retroactive edits. Others are poetic verses repackaged as predictions. And some were never meant to predict anything — they were emotional venting sessions dressed up later as messianic blueprints. Let’s break it all down, category by category, and look at how the sausage of prophecy was actually made.

Post-Event Prophecy (Vaticinium ex Eventu)

Definition:

A prophecy that sounds eerily accurate — because it was written after the events it describes. Think of it as “prophecy with a spoiler.”

Traits:

- Written with knowledge of the outcome

- Loves history in disguise

- Perfect for boosting credibility during tough times

Case in point: Daniel 11. This chapter reads like someone live-tweeting the power struggles between the Seleucid and Ptolemaic empires, except it was written long after the action.

Take this verse: “He shall stir up his power and courage against the king of the south with a great army…” (Daniel 11:25, NRSVue). That’s not a mystic vision — it’s a recap of Antiochus III (Seleucid king) squaring off against Ptolemy V (Egypt) at the Battle of Panium in 200 BCE.

This chapter nails historical detail right up until Antiochus IV Epiphanes — and then falls apart. Why? Because the author had been writing history up to that point and ran out of actual events to draw from. As scholar John J. Collins puts it, “Daniel 11 offers a remarkably detailed account of events up to the time of Antiochus IV, indicating the author's hindsight. The failure to predict Antiochus' death shows where the vision ends and current hope begins” (Collins 112).

Some might say It’s not fraud — it’s motivational literature. But c’mon. The author of Daniel knew that he was lying when he wrote it, and he still wrote it. That is fraud in my book. The simple truth is that Jewish writers during the Maccabean Revolt were under siege, and they needed prophecy that reminded them they were still in God's story — even if they had to backfill some chapters.

Biblical prophecy often skips context in favor of impact. It’s not deception — it’s marketing.

Retrospective Reapplication (Proof texting Poetry)

Definition:

This is where New Testament writers flip open the Psalms, find a dramatic line, and say, “Hey! That sounds a lot like Jesus!” Never mind that the original context was someone else having a really bad day.

Traits:

- Ransacks poetry for prophecy

- Often lifts lines from lament psalms

- Doesn't care much for historical intent

A top-tier example? John 19:24, where Roman soldiers divide Jesus’ clothing. The author claims it fulfills Psalm 22:18: “They divide my clothes among themselves, and for my clothing they cast lots” (NRSVue).

But Psalm 22 is not a prophecy — it's a lament. That’s a genre where people cry, complain, and basically ask God why everything is falling apart. It’s therapy in verse, not a forecast of crucifixion logistics. The psalmist says things like “I am poured out like water, and all my bones are out of joint…” (Psalm 22:14, NRSVue). That’s poetic metaphor, not forensic detail.

This lament style wasn’t unique to the Israelites. The Sumerians were doing the same thing centuries earlier in texts like the Lament for Ur and the Lamentation over the Destruction of Sumer and Ur. As John Walton notes, “The laments of the ancient Near East are filled with the same metaphors—broken bones, consumed cities, nakedness, and weeping gods—that later appear in Hebrew poetry” (Walton 178).

Many gospel moments didn’t fulfill prophecy — they were built to look like they did.

Other Hebrew examples of venting with style include:

- Psalm 69:3 – “I am weary with my crying; my throat is parched.”

- Psalm 6:6 – “Every night I flood my bed with tears; I drench my couch with my weeping.”

So no, the Psalmist wasn’t predicting Roman dice games. He was just having a miserable time — and future authors found his misery oddly useful.

Narrative Backwriting (Prophecy-Driven Plot Design)

Definition:

When the gospel writers are clearly thinking, “We need Jesus to fulfill this prophecy. Let’s write the story accordingly — even if it gets a little awkward.”

Traits:

- Forces a prophecy into the plot like it’s IKEA furniture

- Sometimes misunderstands Hebrew poetic devices

- Prioritizes theological symbolism over realism

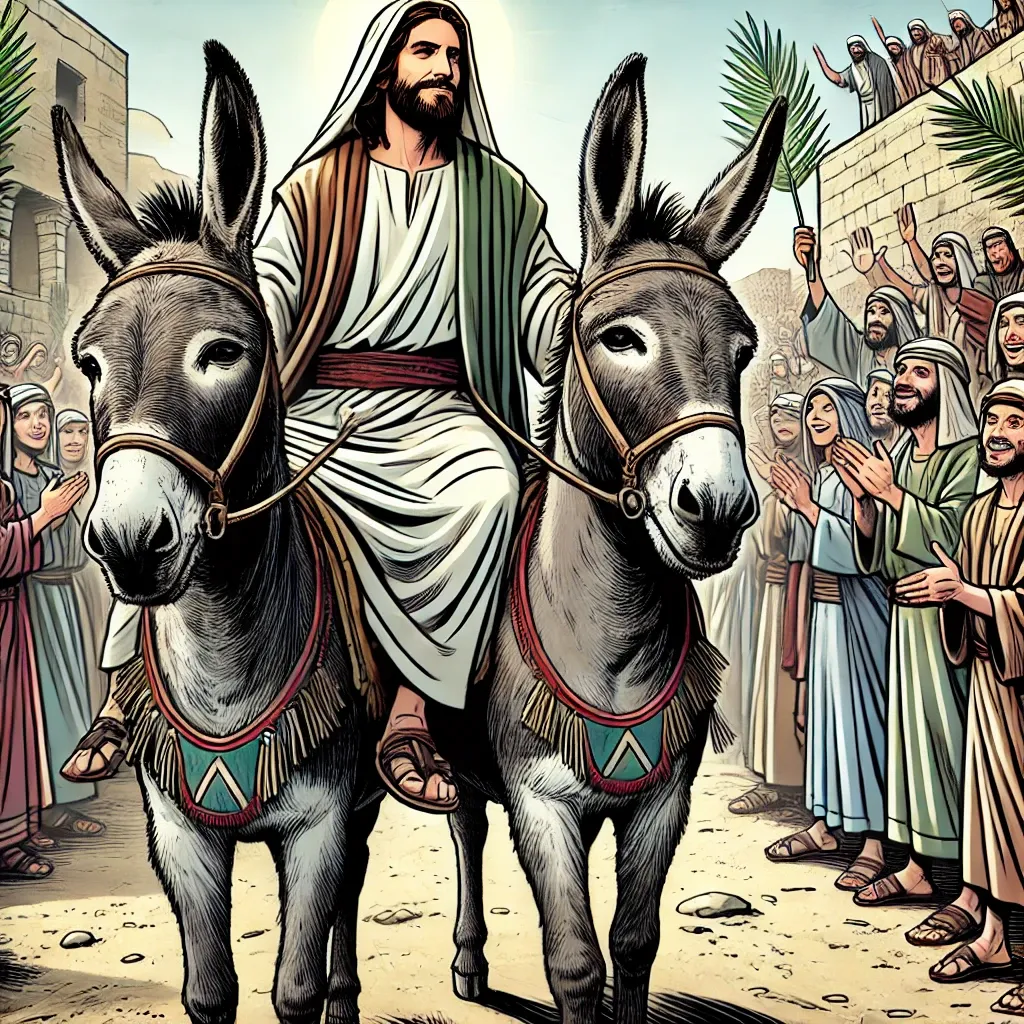

The most facepalm-worthy example comes in Matthew 21:7, where Jesus enters Jerusalem not on one donkey, but two: “They brought the donkey and the colt and put their cloaks on them, and he sat on them” (NRSVue). Get that image straight in your mind. Jesus entered Jerusalem riding two donkeys at once. Ever tried to ride two animals at once? Same. Maybe they were exceedingly skinny donkeys, and extremely cooperative.

Why two? Because Matthew was trying to fulfill Zechariah 9:9: “your king comes to you… humble and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey” (NRSVue). But Zechariah was using Hebrew poetic parallelism — a fancy way of repeating the same thing twice for emphasis, not describing a donkey parade.

This poetic doubling shows up all over the Old Testament:

- Psalm 24:1 – “The earth is the Lord’s and all that is in it, the world, and those who live in it.”

- Isaiah 2:4 – “They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks…”

Matthew, bless his heart, took the text literally and became the butt of many a bible scholar’s ridicule as a result. As Raymond E. Brown notes, “The dual animal imagery is not historical but results from a literalist reading of Zechariah’s poetry” (Brown 104).

So did Jesus actually ride two animals at once? Probably not. But for Matthew, getting the prophecy to fit was more important than staging logistics.

Recontextualized Prophecy

Definition:

The original meaning of the prophecy? Forget that. We’re applying it to something new, because it fits now — and because theological imagination has no expiration date.

Traits:

- Recycles and repurposes old oracles

- Often changes the identity of the original subject

- Driven by new needs and fresh crises

The heavyweight champion of this category is Isaiah 53, the “Suffering Servant” chapter. It paints a haunting picture: “He was despised and rejected by others… he has borne our infirmities… by his bruises we are healed” (Isaiah 53:3–5, NRSVue).

Christians read this and immediately think of Jesus. But hold up — Isaiah already tells us who the servant is. Two chapters earlier in Isaiah 49:3, God says: “You are my servant, Israel, in whom I will be glorified” (NRSVue). We see the same in Isaiah 41:8–9, where Israel is again explicitly called God’s servant.

This wasn’t a messianic teaser. It was political theology written during the Babylonian exile. Jerusalem had been trashed in 586 BCE, and the people were living in a humiliating foreign captivity. The “servant” is a symbol of Israel — beaten down, yes, but still in covenant with God.

The hope blooms in Isaiah 54, which follows the suffering servant with promises of restoration: “You shall forget the shame of your youth… For the mountains may depart and the hills be removed, but my steadfast love shall not depart from you” (Isaiah 54:4, 10, NRSVue).

The suffering was national, not personal. But the New Testament writers — creatively and devotionally — reframed it to describe Jesus. James Kugel writes, “Ancient interpreters were not bound by original context; rather, they sought meaning for their present situation in the text’s deeper layers” (Kugel 128).

In other words: context, shmontext. If it fits the moment, it’s fair game.

Conclusion

Biblical prophecy isn’t just about fortune-telling. It’s layered, strategic, emotional, and — let’s be honest — sometimes retrofitted. Some "prophecies" were written with the benefit of hindsight. Others were ripped out of context and repackaged for theological effect. And still others were poetic venting sessions turned into roadmaps for the Messiah.

This doesn’t mean it’s all fake. But it does mean we should read carefully. Not every “fulfilled prophecy” is a mic-drop from heaven. Sometimes, it’s just smart storytelling — or a desperate attempt to find meaning when everything’s falling apart.

Works Cited

Brown, Raymond E. An Introduction to the New Testament. Yale University Press, 1997.

Collins, John J. Daniel: With an Introduction to Apocalyptic Literature. Eerdmans, 1984.

Ehrman, Bart D. Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press, 1999.

Kugel, James L. How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now. Free Press, 2007.

Walton, John H. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Baker Academic, 2006.

New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition. Holy Bible. National Council of Churches, 2021.