The Horse’s Teeth Parable: Why False Attribution Persists When Authority Replaces Evidence

A humorous parable about counting a horse's teeth reveals how critical inquiry—and a good look in the barn—can outdo centuries of inherited authority and forged authorship.

I first encountered the Horse’s Teeth Parable in college.

A professor recounted it as a medieval anecdote: a group of monks arguing endlessly over how many teeth a horse possesses. They consult authorities, debate precedent, and appeal to tradition. When a novice suggests the obvious solution—opening the horse’s mouth—he is rebuked for impiety. The debate continues. The truth remains unresolved.

The story worked. It was tidy, memorable, and seemed to capture something real about intellectual inertia: the tendency to argue about reality rather than examine it. Like many students, I filed it away as a clever illustration of scholastic excess and moved on.

Years later, the story came back to me—not because of its moral, but because of its polish. It was almost too perfect, too neatly aligned with modern frustrations about theory divorced from evidence. That lingering discomfort eventually prompted a simple question: where did this story actually come from?

I decided to do the one thing the monks in the parable never do. I checked.

What I found was that the Horse’s Teeth Parable itself illustrates the very problem it satirizes. It is not medieval. It is a modern construction, confidently attributed to the past without verification.

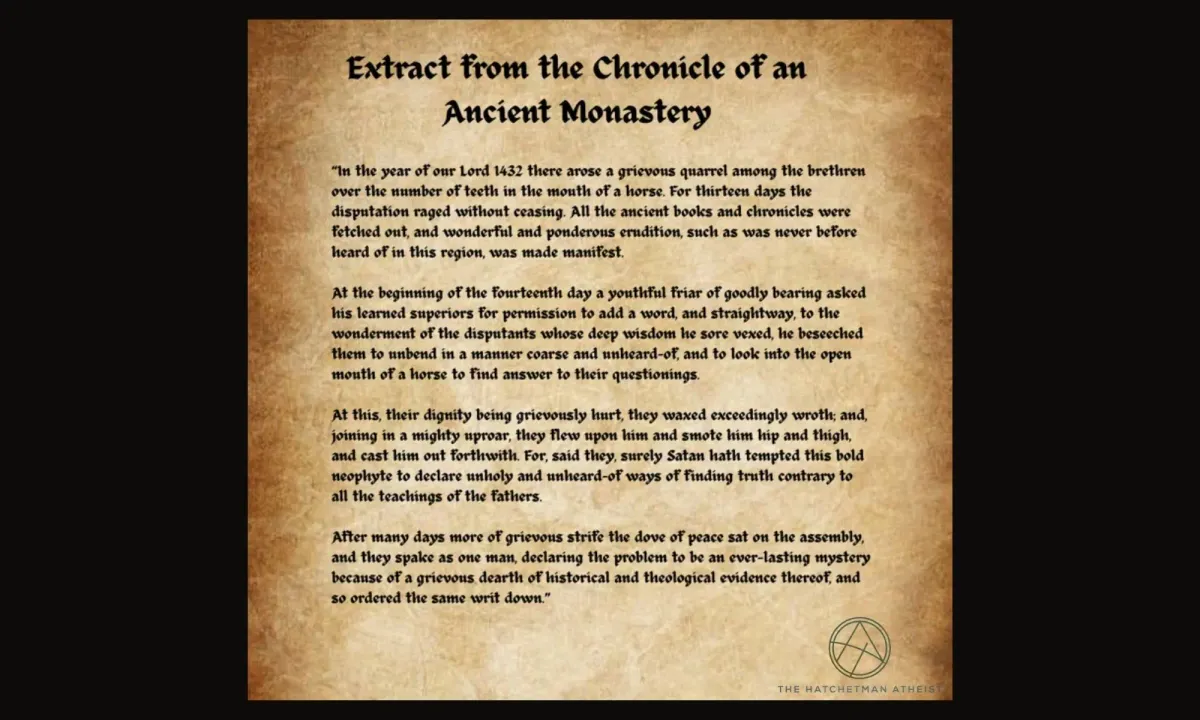

Despite its archaic tone and monastic setting, there is no manuscript evidence placing the parable anywhere near the Middle Ages. It does not appear in fifteenth-century chronicles. No medieval author references it. The earliest documented appearance of the text dates to 1901, when it was published in the Monthly Journal of the International Association of Machinists under the title Chronicle of an Ancient Monastery. It was presented as satire.

Over time, the satirical frame fell away. The story began circulating as a genuine historical anecdote. In some retellings, it was attributed to figures like Francis Bacon or Roger Bacon—names chosen not because they were correct, but because they carried intellectual authority. The parable gained weight not through evidence, but through attribution.

This pattern is neither unusual nor confined to harmless anecdotes. The appeal of the Horse’s Teeth Parable does not rest on its historical accuracy; it rests on its rhetorical usefulness. By attaching the story to the Middle Ages—or to a respected thinker—it feels older, wiser, and therefore truer. The lesson seems validated by antiquity rather than argument.

This same mechanism appears repeatedly in claims about religious history, especially those built on superficial resemblance rather than primary sources. I explore that pattern in detail in Parallelism: Why Everything Isn’t a Copy of Something Older

https://the-hatchetman-atheist.ghost.io/parallelism-because-apparently-everything-is-a-copy-of-something-older/

In intellectual history, this move is common. Claims gain traction not because they are well supported, but because they are well attributed. Authority arrives first. Evidence is supplied later, if at all.

There is a term for this practice: pseudepigraphy. Pseudepigraphy refers to the attribution of a text to a more authoritative or prestigious figure in order to enhance its credibility. It is not always motivated by deliberate fraud. Often, it is motivated by persuasion. A message believed to come from the right source is more likely to be accepted, even when its actual origins are uncertain.

The Horse’s Teeth Parable functions this way. Its false antiquity gives it rhetorical force. The story is believed because it sounds old and feels plausible. The very instinct it criticizes—the substitution of authority for observation—is the instinct that sustains it.

This is the same dynamic that underlies many popular claims about Christian origins, including assertions that Jesus was simply copied from earlier pagan gods. A detailed example can be found in Horus and Jesus: The Truth About Plagiarism Claims

https://the-hatchetman-atheist.ghost.io/jesus-horus-myth-debunked/

The mechanism also appears in debates over biblical authorship itself. The New Testament contains several well-known examples of disputed authorship. Modern scholarship widely agrees that the Pastoral Epistles—1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus—were written decades after Paul’s death. Linguistic patterns, theological concerns, and historical context all point away from Pauline authorship. Yet for centuries, these letters were accepted as authentic, their authority resting on attribution rather than evidence.

A similar pattern appears in the Book of Daniel. Although the text is set during the Babylonian exile of the sixth century BCE, it reflects detailed knowledge of events from the Maccabean period centuries later. Its prophecies track known history with remarkable accuracy until the point where history ends and prediction begins—at which point they fail. Here too, attribution preceded verification. The text was believed first. Critical scrutiny came much later.

This is why skepticism often focuses less on conclusions than on methods. I address that distinction directly in A Quick Note About Evidence

https://the-hatchetman-atheist.ghost.io/why-atheists-dismiss-religious-evidence

Seen in this light, the enduring appeal of the Horse’s Teeth Parable is unsurprising. Despite its false provenance, it remains effective because it illustrates a real human tendency: the preference for argument over observation when observation threatens established authority. The lesson is not invalid because the story is modern. It becomes misleading only when its illustrative value is mistaken for historical fact.

There is a quiet irony in all of this. Uncovering the truth about the parable required precisely the kind of inquiry the story advocates. Rather than debating how old it ought to be, the solution was simply to look.

The Horse’s Teeth Parable is not medieval. It is not monastic. It is not ancient.

But it is instructive.

And like the monks in the story, we are always tempted to argue about authority when evidence is close at hand—waiting, patiently, for someone to open the horse’s mouth.

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so on patreon.

Works Cited

Chronicle of an Ancient Monastery. Monthly Journal of the International Association of Machinists, vol. 13, no. 3, 1901, p. 129.