What Is an Evangelical Christian?

Most people use the term "Evangelical" without fully understanding its roots. Discover how Christianity evolved from a unified institutional church into a fragmented landscape of personal experience, revivalism, and the "born-again" identity.

Evangelical Christianity refers to a broad family of Protestant movements that emphasize personal conversion, the authority of the Bible, and an experiential relationship with God. Although the term is widely used in political, cultural, and religious contexts, it is often invoked without a clear understanding of where evangelicalism came from or how it differs from other forms of Christianity.

Evangelical Christianity is one of those terms that gets thrown about with reckless abandon without the speaker or listener really knowing what the term means. Most people have a vague idea, but it is easy to get confused when there are so many denominations, and few people want to sit around reading church history just to understand how everything fits together.

This post was designed to save that time for the reader by briefly encapsulating the major types and eras of Christianity and explaining how evangelicalism fits into the larger picture.

Modern evangelicalism cannot be understood unless it is seen as a point at the end of a long historical sequence. What follows is a high-level overview of the major eras of Christianity and the historical developments that brought evangelicalism into existence.

Table of Contents

- The Catholic Era

- The Protestant Era

- The Proto-Evangelical Era

- The Pentecostal and Modern Evangelical Era

- Frequently Asked Questions

The Catholic Era

Institutional Christianity in the West

For most of its institutional history in the West, Christianity existed under a single ecclesiastical structure. Authority flowed downward through bishops and clergy, doctrine was stabilized through councils,[4] and salvation was mediated through sacraments administered by the church.[1] This arrangement created continuity and discipline, but it also concentrated power.

The East–West Schism

The first major rupture came with the East–West split of the eleventh century, usually referred to as the Great Schism. Christianity divided into a Latin-speaking Western church and a Greek-speaking Eastern church. The split was driven less by core theology than by language, politics, and competing claims of authority. The result was not two competing denominations, but two Christian civilizations that developed separately: the Latin church in the West and the Greek church in the East.

The Protestant Era

The Reformation and Structural Fragmentation

The second and far more destabilizing rupture arrived with the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century. Reformers rejected papal authority,[2] challenged sacramental control over salvation,[1] and elevated scripture above church tradition.[5] Unlike the earlier schism, this break did not stabilize into two enduring poles. Once centralized authority was rejected, Christianity became structurally open-ended. Fragmentation was no longer a failure mode; it became the system’s default.

As a result, the Western church, which had already split from the East, was divided again into two broad camps: Catholic and Protestant. This division became known as the Protestant Reformation.

The Rise of Mainline Protestantism

After the Reformation, Protestantism did not remain chaotic for long. It rebuilt institutions. Distinct church traditions emerged with trained clergy, formal confessions, governing bodies, and seminaries. Over time, these became what were known as mainline Protestant churches.[6]

Despite their doctrinal differences, these churches shared several defining traits. Christianity was understood primarily as a communal and inherited identity. Faith was transmitted through education, catechism, and participation in church life. Conversion was possible, but it was not central. Emotional experience was not required. Doubt was not disqualifying. A person was Christian largely because they were raised within the system.

This was still institutional Christianity. It was Protestant, but it was not evangelical.

The Proto-Evangelical Era

Revivalism and the Great Awakenings

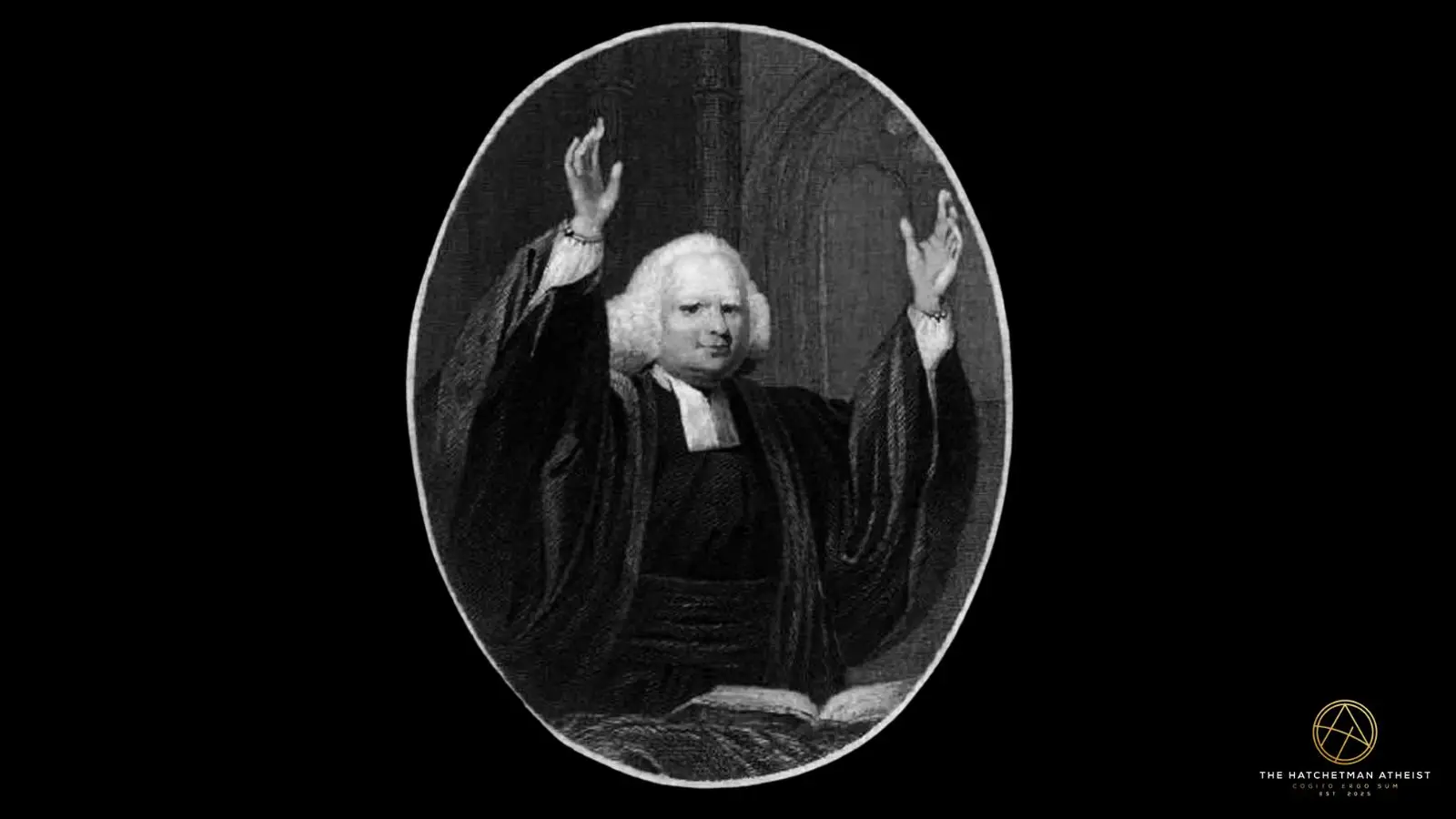

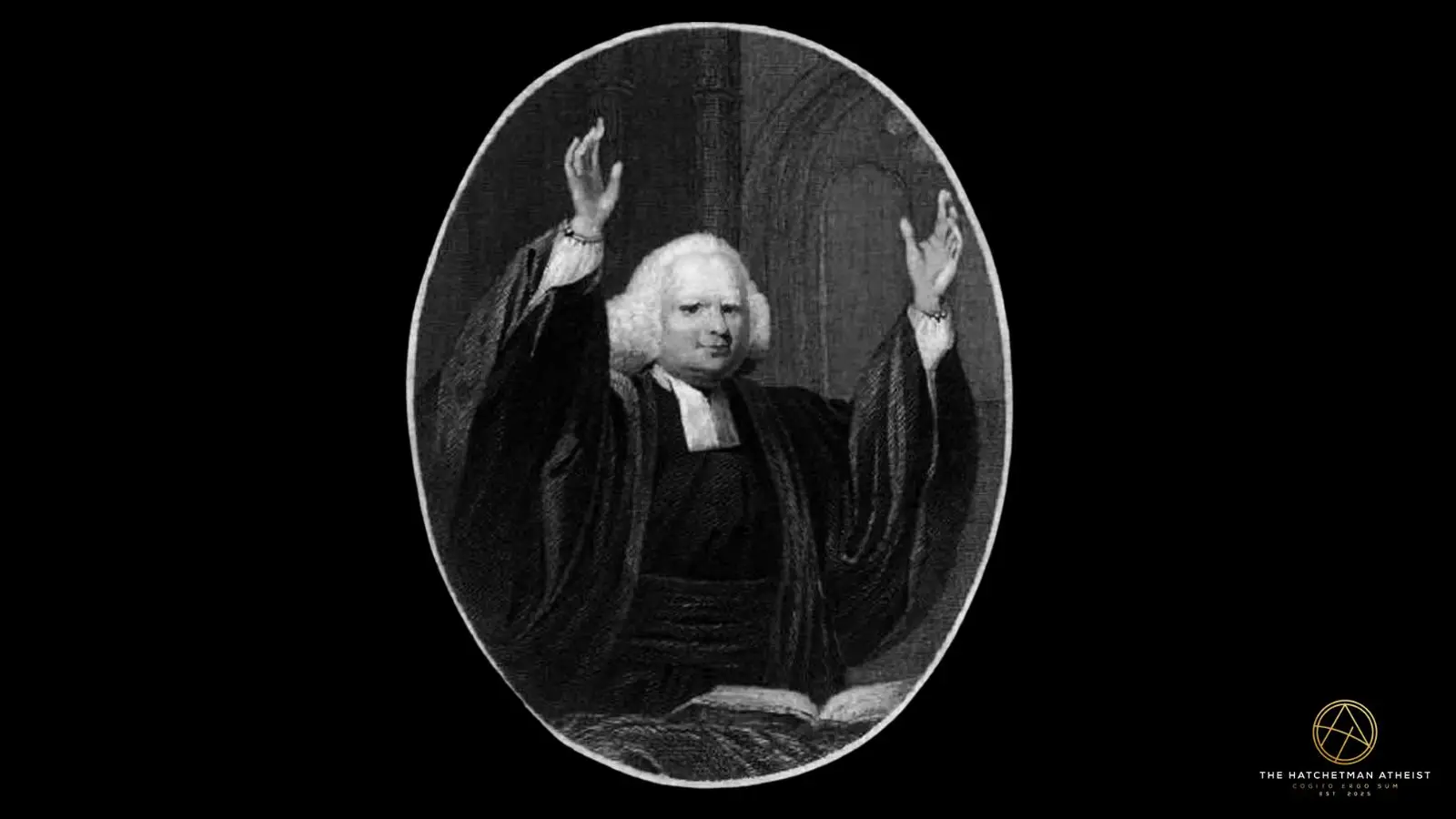

By the eighteenth century, critics within Protestantism began to see these institutions as spiritually inert. Churches were orderly, educated, and stable, but were increasingly perceived as lifeless. Revivalism emerged as a corrective, reframing Christianity around personal transformation rather than inherited belief.

Preachers associated with the Great Awakenings argued that church membership did not save a person. Only a personal encounter with God did.[3] Salvation became a distinct moment rather than a gradual formation. Emotional conviction became evidence of sincerity. Testimony became proof of faith. Christianity shifted from something a person was to something that happened to them.

New Movements Born of Revival

Preachers were less formal. They preached in the open air to hundreds of people at a time. Listeners were sometimes reported to have broken down into fits of crying or uncontrollable shaking due to the raw emotion they experienced while listening to sermons.

Out of this revivalist soil emerged new movements. Methodism expanded rapidly. Baptist congregations multiplied. Restorationist groups attempted to strip Christianity down to what they imagined as its original form. Apocalyptic currents intensified, eventually producing Adventist movements centered on expectation, urgency, and prophetic certainty. What united these developments was not theology, but the primacy of experience.

The Pentecostal and Modern Evangelical Era

Pentecostalism and the Turn Toward Experience

The final transformation occurred in the early twentieth century, when revivalism intensified into a fully experience-centered form of Christianity with the emergence of Pentecostalism. Conversion alone was no longer sufficient. Authentic faith now required direct, observable interaction with the Holy Spirit.

Practices such as speaking in tongues, prophecy, healing, and physical manifestations were no longer marginal. They were treated as signs of legitimacy. This shift accelerated dramatically after the Azusa Street revival beginning in 1906. From that point forward, Christianity—at least in its fastest-growing forms—was no longer anchored primarily in doctrine or institution, but in felt spiritual experience.

The Rise of the Born-Again Identity

This was where the modern idea of the born-again Christian fully took shape.[7] Being Christian was defined not by baptism, catechism, or denominational identity, but by an internal event interpreted as a spiritual rebirth. Belief became secondary to experience. Experience became self-validating.

Evangelical groups that existed prior to Pentecostalism generally rejected the idea of speaking in tongues and other gifts of the Spirit that Pentecostals valued. This effectively created another internal divide between traditional evangelicals and the emerging charismatic movement.

Even evangelical groups that rejected overt Pentecostal practices absorbed this broader experiential framework. Worship became emotionally driven. Sermons prioritized personal transformation. Absence of experience was treated as spiritual failure. The older Protestant model of quiet belief gave way to a system in which certainty was generated from within.

Modern evangelicalism was not ancient Christianity preserved. It was Christianity re-engineered around experience, optimized for emotional immediacy, and detached from historical continuity.

Other posts you might be interested in:

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a revival?

A revival is a period of heightened religious enthusiasm, usually marked by large public gatherings, emotionally charged preaching, and a surge in conversions. Revivals are not routine church services. They are special events intended to “revive” what participants believe is a spiritually stagnant or complacent Christianity.

Historically, revivals often take place outside traditional church buildings and draw people from wide geographic areas. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, attendees frequently travelled long distances and camped at the site, giving rise to what becomes known as the camp meeting. Revivals emphasize urgency, personal decision, and emotional response rather than ritual or formal theology.

What is a “Holy Roller”?

“Holy Roller” is a colloquial—and often mocking—term used to describe Christians whose worship involves intense physical expression. This can include rolling on the floor, shaking, shouting, crying, or other uncontrolled bodily movements during religious services.

The term emerges in response to revivalist and Pentecostal worship styles, especially in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when such behavior appears shocking or undignified to outsiders accustomed to structured church services.

What does the term “Holy Roller” mean?

The phrase combines two ideas. “Holy” refers to the Holy Spirit, which participants believe is actively moving through their bodies. “Roller” refers literally to rolling on the ground, though it is also used more broadly to describe dramatic physical responses during worship.

Although the term is usually pejorative, some believers embrace it as a mark of authenticity, interpreting physical manifestations as evidence of genuine spiritual experience.

What is a cessationist?

A cessationist is a Christian who believes that certain supernatural “gifts of the Spirit”—such as speaking in tongues, prophecy, and miraculous healing—ceased after the apostolic age.

Cessationism is common among many Protestant traditions that predate Pentecostalism. These groups typically hold that miraculous gifts were necessary for the founding of the church but are no longer normative today. This belief historically places them in conflict with Pentecostals, who maintain that these gifts have returned—or never ceased at all.

In recent decades, some churches that were historically cessationist have accepted the validity of speaking in tongues or other charismatic gifts, while still discouraging or marginalizing their use in regular worship.

What is a testimony?

A testimony is a personal narrative describing how someone becomes a Christian or experiences spiritual transformation. In evangelical and revivalist settings, testimonies function as social proof of faith.

A typical testimony includes a description of life before conversion, a crisis or turning point, and a sense of inner change or rebirth. In many evangelical communities, having a testimony is treated as evidence that one is a “real” Christian.

What do evangelicals believe about the Bible?

Evangelicals generally believe that the Bible is the ultimate authority in matters of faith and morality. Many hold that the Bible is divinely inspired in a way that sets it apart from all other religious or historical texts.

In more conservative evangelical circles, this belief often takes the form of biblical inerrancy, the idea that the Bible contains no errors of any kind in its original manuscripts. Other evangelicals adopt less rigid views while still treating the Bible as uniquely authoritative.

What is the difference between inspiration, inerrancy, and literalism?

Inspiration refers to the belief that the Bible is inspired by God in some meaningful sense.

Inerrancy is the belief that the Bible, in its original form, contains no errors, whether theological, historical, or scientific.

Literalism is an interpretive approach that treats biblical texts as straightforward factual descriptions unless explicitly marked as symbolic.

These terms are often conflated, but they are not identical. A person may believe the Bible is inspired without believing it is inerrant, and a person may believe it is inerrant without interpreting every passage literally.

What are some examples of mainline Protestant churches?

Mainline Protestant churches are historically established Protestant denominations that emphasize institutional continuity, formal clergy, and theological education.

Common examples include:

- Anglicans

- Episcopalians

- Presbyterians

- Lutherans

What are some examples of evangelical churches (non-Pentecostal)?

Evangelical churches that are not Pentecostal typically emphasize personal conversion and biblical authority while rejecting or downplaying charismatic gifts such as speaking in tongues.

Examples include:

- Southern Baptist churches

- many independent Bible churches

- conservative Presbyterian and Reformed churches

- evangelical Methodist churches and holiness churches that emphasize conversion but reject charismatic gifts

What are some examples of Pentecostal churches?

Pentecostal churches explicitly teach that the Holy Spirit actively manifests through gifts such as speaking in tongues, prophecy, and healing.

Examples include:

- the Assemblies of God

- the Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee)

- Foursquare Churches

- the International Pentecostal Holiness Church

- the United Pentecostal Church (oneness or Jesus Name Pentecostals, sometimes referred to as “Apostolics”)

- many independent charismatic churches

Over time, Pentecostal beliefs also spread into non-Pentecostal denominations through the Charismatic Movement, blurring traditional boundaries between church categories.

https://the-hatchetman-atheist.ghost.io/content/images/2026/01/jimmy-swaggart.webp

https://the-hatchetman-atheist.ghost.io/content/images/2026/01/billy-graham-bw-pulpit.webp

https://the-hatchetman-atheist.ghost.io/content/images/2026/01/george-whitefield-inline.webp