Did Jesus Really Exist?

Ancient history doesn’t deal in proof; it deals in likelihood. Discover why the most awkward and uncomfortable stories about Jesus—from his baptism to his execution—are precisely the ones historians take most seriously.

Why Historians Take Embarrassing Evidence Seriously

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Problem of Biased Sources

- What the Criterion of Embarrassment Is (and Is Not)

- Why Embarrassing Material Survives

- Embarrassing Data in the Jesus Traditions

- Why a Fictional Jesus Would Look Different

- Probability, Not Proof

- Why This Matters

- Appendix: Scriptural Passages Referenced in This Essay

Introduction

Ancient history does not deal in proof. It deals in likelihood.

In a previous essay, I argued that Jesus is best understood as a first-century apocalyptic preacher whose expectations failed and whose significance was reshaped only after his execution. That reconstruction explains what early Christianity had to reinterpret. This post addresses a different question: how historians decide whether such a figure is more likely to have existed at all. The criterion of embarrassment is one of the tools used in that assessment—not to prove anything, but to weigh probability when all surviving sources are biased.

This article is part of a four-post series examining Jesus through the lens of historical method rather than theological expectation. Related essays:

This point is routinely misunderstood in debates about Jesus. Skeptics often demand certainty; apologists sometimes pretend to offer it. Historians do neither. They work with incomplete, biased, and fragmentary sources and ask a different question altogether: what explanation best accounts for the evidence we actually have?

The so-called “criteria” used in historical Jesus research are not rules that mechanically generate truth. They are heuristics—tools for weighing probability when direct evidence is unavailable. Among them, the criterion of embarrassment is one of the most frequently misunderstood and one of the most quietly effective.

Used correctly, it does not prove that any particular event happened. What it does is help historians distinguish between memory and invention in traditions that are openly partisan.

The Problem of Biased Sources

Virtually all of our sources for Jesus come from people who believed in him. This fact is often treated as fatal to historical inquiry, but in ancient history it is routine. Most figures from antiquity are known through followers, admirers, or hostile critics—each with their own distortions.

The real question is not whether sources are biased, but how bias behaves.

When authors invent stories to promote a cause, they tend to:

- portray founders as competent and authoritative,

- smooth over failures,

- and eliminate details that undermine legitimacy.

When authors transmit traditions they have inherited—especially traditions already circulating widely—they often preserve material that is inconvenient, awkward, or difficult to reconcile with later beliefs. Instead of deleting such material, they reinterpret it.

The criterion of embarrassment is designed to identify this pattern.

What the Criterion of Embarrassment Is (and Is Not)

At its core, the criterion of embarrassment rests on a simple observation: details that work against an author’s interests are less likely to have been invented by that author.

This does not mean:

- that embarrassing details are automatically true,

- that ancient authors never invented awkward material,

- or that embarrassment functions independently of context.

What it means is narrower and more cautious: when a tradition contains elements that create theological, social, or ideological problems for the people transmitting it, those elements are more plausibly inherited than fabricated.

The criterion is probabilistic. It raises likelihood; it does not confer certainty.

Why Embarrassing Material Survives

Embarrassing traditions survive for a simple reason: they become fixed early.

Before Christianity developed formal doctrine, it existed as a movement bound together by memory, oral transmission, and shared stories. By the time later authors composed narrative accounts, much of this material was already familiar to their communities. It could be reinterpreted, contextualized, or reframed—but not easily erased without raising questions.

This produces a recurring pattern in the sources: awkward material is not removed; it is surrounded by explanation.

That pattern is historically informative.

Embarrassing Data in the Jesus Traditions

Applied carefully, the criterion of embarrassment highlights several features of the Jesus tradition that are difficult to explain as invention.

1. Jesus’ Baptism by John

Baptism in this context implies submission. It places John the Baptist in a position of superiority and associates Jesus with a ritual linked to repentance. For a movement that later proclaimed Jesus as sinless and supreme, this posed an immediate problem.

The tradition responds not by denying the baptism but by explaining it away. John protests. The act is reframed. Divine approval is emphasized. The discomfort is visible.

This is not how fictional hierarchy is normally constructed. It is how inherited memory is managed.

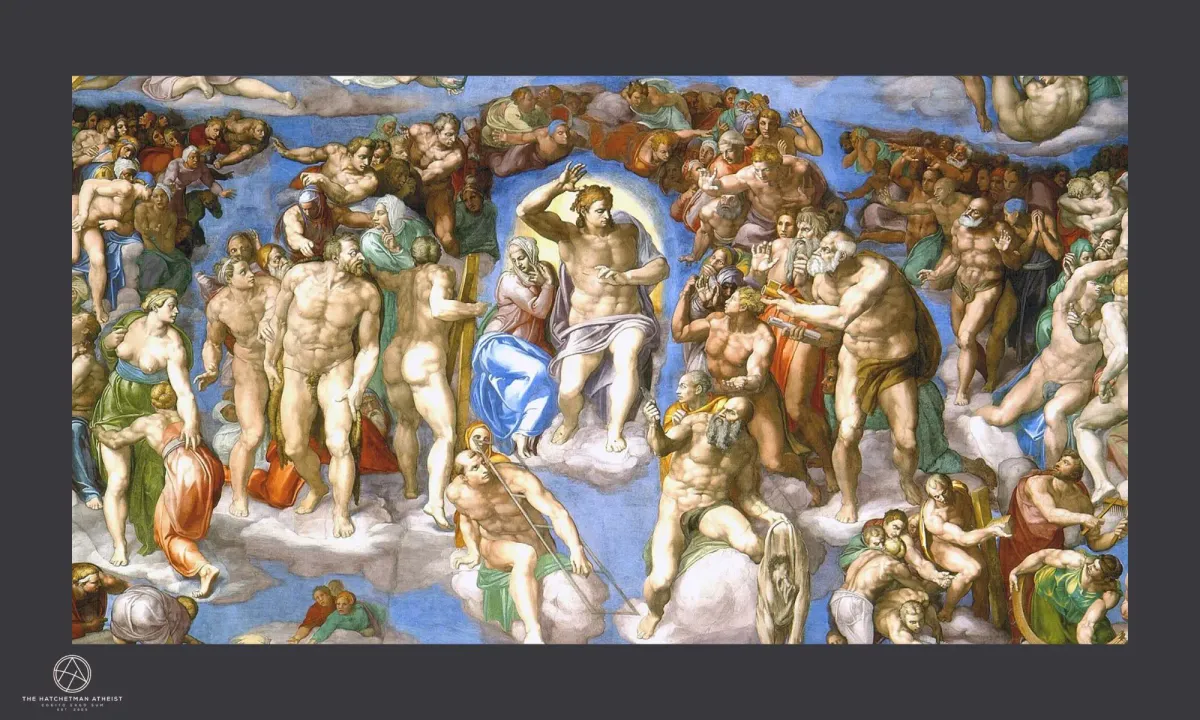

Andrea del Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci, The Baptism of Christ (c. 1470–1475). This tradition places John the Baptist in a position of ritual authority over Jesus, a hierarchy later theology was forced to explain rather than erase.

Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 4.0 International.

2. Jesus’ Family’s Apparent Skepticism

Several traditions depict Jesus’ own family as misunderstanding him, doubting him, or attempting to restrain him. In a culture that valued lineage and household honor, this is not a flattering portrait—especially once family members later became respected figures within the movement.

A fictional founder is rarely portrayed as misunderstood by his own household. The tension serves no obvious propagandistic function and creates unnecessary narrative friction.

Here again, later tradition does not erase the problem. It absorbs it.

3. Jesus’ Execution by Crucifixion

Crucifixion was a degrading, public form of execution reserved for criminals and political threats. Within Jewish apocalyptic expectations, it marked failure, not vindication. A messiah executed by Rome without resistance or divine intervention was, by definition, a failed messiah.

Christian theology eventually transformed this outcome into a salvific necessity. But that transformation itself points backward to a prior embarrassment. No movement inventing a messianic figure from scratch would begin with an execution that invalidated its central claims.

The crucifixion had to be explained because it happened.

4. Jesus’ Cry of Abandonment

The tradition that Jesus cried out in despair at the moment of death is striking precisely because it undermines later claims of confident foreknowledge and divine orchestration. It presents a figure experiencing abandonment, not triumph.

This is not the emotional register one expects from theological invention. It is the kind of detail that survives because it was remembered, not because it was useful.

Related Essay

For a fuller reconstruction of how this failed apocalyptic expectation was later reinterpreted into Christian theology, see:

Jesus, Apocalyptic Failure, and Messianic Retrofit

Why a Fictional Jesus Would Look Different

When religious movements invent founders or heroes, certain patterns recur:

- the founder understands his role clearly,

- defeats are minimized or externalized,

- and legitimacy is emphasized from the outset.

The Jesus tradition displays the opposite pattern:

- uncertainty about identity,

- theological scrambling,

- and reinterpretation layered over failure.

This does not prove historicity. But it does make pure invention a poorer explanation than the existence of an underlying historical figure whose life did not conform to later expectations.

Probability, Not Proof

No single embarrassing detail establishes that Jesus existed. That is not how historical reasoning works.

What matters is convergence:

- multiple independent traditions,

- preserved despite discomfort,

- requiring explanation rather than deletion.

Each instance slightly raises the probability that the tradition reflects memory rather than fabrication. Taken together, they form a cumulative case—modest in each component, but compelling in aggregate.

This is why the overwhelming majority of professional historians, including those with no theological commitments, regard Jesus’ existence as more likely than not. Not because the evidence is pristine, but because alternative explanations account for the data less well.

Why This Matters

The criterion of embarrassment is not a trick for rescuing belief. It is a window into how traditions behave under pressure.

Used carefully, it shows that the Jesus of history looks less like a character invented to succeed and more like a person whose failure demanded reinterpretation. That conclusion does not tell us what to believe about him. It tells us why historians take his existence seriously.

And in ancient history, seriousness is the strongest claim anyone ever gets.

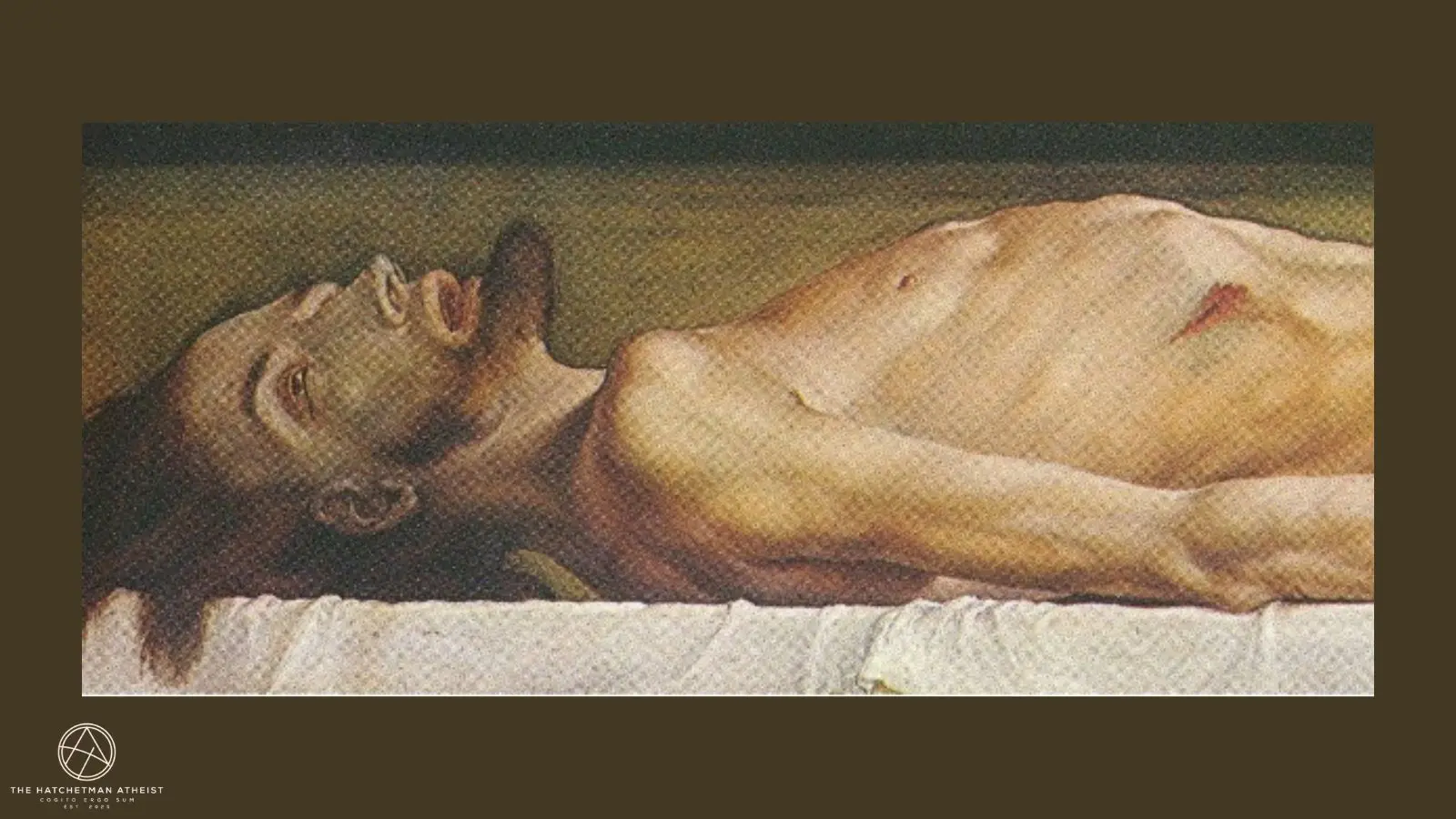

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1521–1522). A depiction of death without transcendence, underscoring the historical problem later theology was forced to resolve.

Public domain.

Appendix: Scriptural Passages Referenced in This Essay

The following passages are listed solely to orient readers to where the traditions discussed in this essay appear in the canonical gospels. Their inclusion does not imply historical reliability or theological endorsement.

Jesus’ baptism by John

Mark 1:9–11

Matthew 3:13–17

Luke 3:21–22

Jesus’ family’s apparent skepticism or misunderstanding

Mark 3:20–21

Mark 3:31–35

John 7:3–5

Jesus’ execution by crucifixion

Mark 15:24–39

Matthew 27:35–54

Luke 23:33–49

John 19:16–30

Jesus’ cry of abandonment

Mark 15:34

Matthew 27:46