The Geological Impossibility of Noah's Flood

A global flood is not only unsupported by science, it’s outright impossible under the laws of geology, hydrology, and physics. This essay explains why Noah’s Ark could never have existed.

The story of Noah’s Ark begins with a worldwide flood—an event that, if it actually happened, would have left unmistakable scars in the Earth’s crust. The problem is simple: geology doesn’t agree. A global flood is not only unsupported by the physical record, it’s outright impossible under the laws of hydrology and physics.

Where Would All the Water Come From?

Genesis describes a flood so massive it covered the highest mountains. To do that today, sea levels would have to rise more than 29,000 feet—enough to submerge Mount Everest. But Earth doesn’t have that much water. Even if you melted every polar ice cap and glacier, sea levels would only rise about 230 feet (Cline 72). Montgomery notes in The Rocks Don’t Lie that there is simply not enough available water on the planet to cover Earth’s highest peaks (Montgomery 186).

Some defenders propose a “vapor canopy” or underground reservoirs. Neither holds water—literally. The atmosphere couldn’t contain enough moisture without heating the planet to thousands of degrees Celsius (Hirschboeck 3). As for subterranean sources, most of Earth’s deep water is chemically bound to minerals and cannot simply pour out. To release it would require breaking down those minerals through extreme chemical and geological processes—something that has never happened on a planetary scale. This means the water is locked inside the rock itself, not stored in caverns waiting to gush out (Montgomery 186).

Where Would All the Water Go?

The Bible says the floodwaters receded in about 150 days (Gen. 8:3). But if the entire world were under water, where would it have gone? In a normal local flood, rivers overflow their banks, flood miles of territory, and then slowly drain via streams and aqueducts into reservoirs—lakes or, ultimately, the ocean. But if the whole Earth were already covered in one vast ocean, that process would break down. There would be no rivers, no drainage, and no lower reservoir for the water to flow into—the drainage has already occurred once the world is ocean. In other words, if Earth is already one unwalled ocean, nothing more can drain because there's no land, no gradient, and no discharge point. There is no ocean reservoir into which the flood waters can recede, because the entire Earth is the ocean.

Evaporation is also not a viable solution. To remove enough water to expose Earth’s mountains in 150 days, evaporation would have to operate on a scale that would release catastrophic amounts of latent heat into the atmosphere. In simple terms, when water vapor condenses into liquid droplets (rain), it releases stored heat. The more water condensed, the more heat is released. If trillions of tons of water evaporated and then condensed this quickly, the amount of heat energy released would superheat the atmosphere to deadly levels (Gornitz, Rosenzweig, and Hillel 48).

Missing Evidence in the Rocks

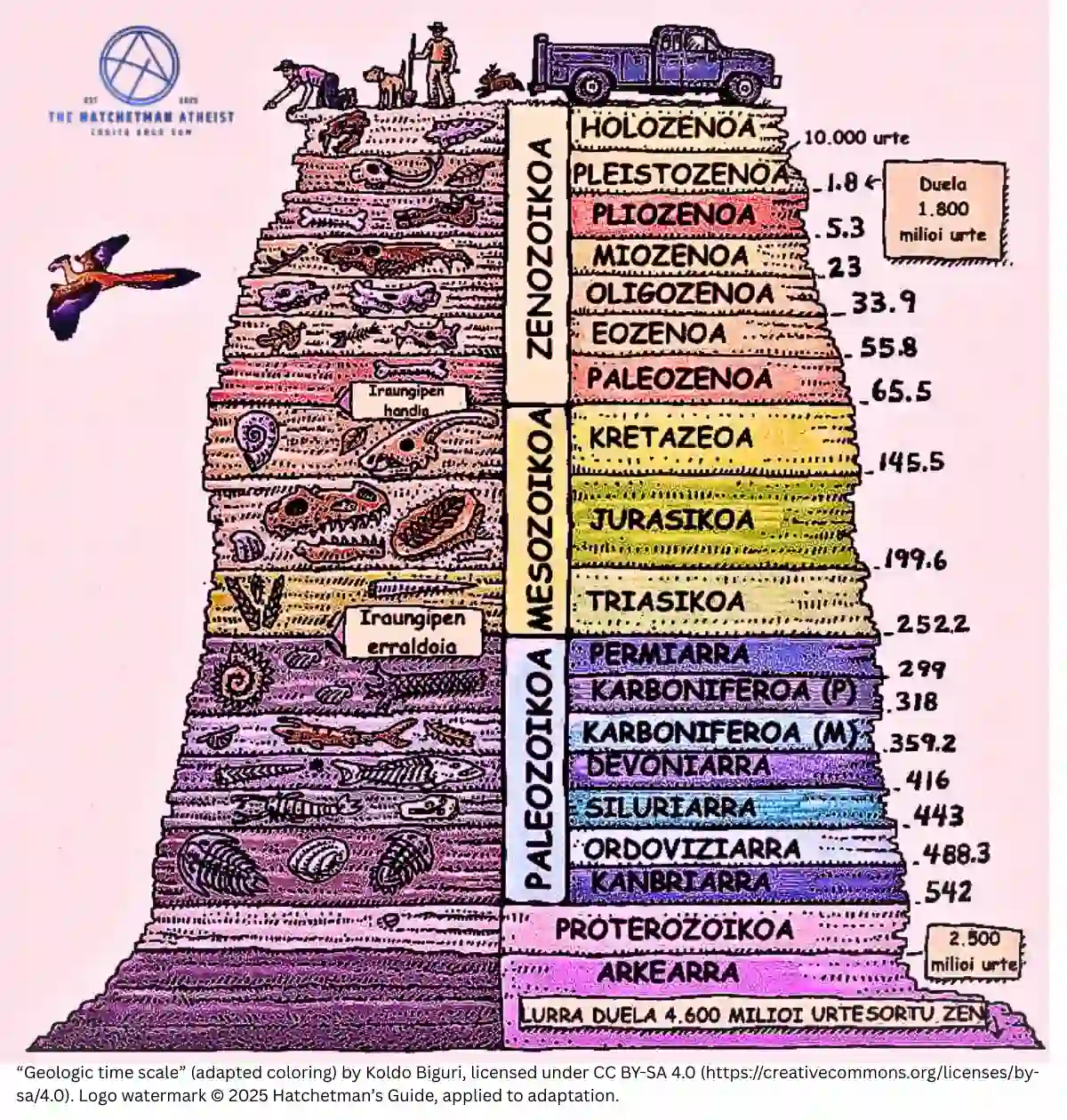

If every living thing died in one catastrophic flood, the fossil record would show it. Instead, fossils are neatly arranged in a logical sequence—trilobites below dinosaurs, dinosaurs below mammals—rather than jumbled together in a single watery grave. Geologist Donald Prothero emphasizes that there is no global sedimentary record consistent with a worldwide flood, only layers that reflect millions of years of gradual deposition (Prothero 112).

Some defenders claim the order of fossils is because more “advanced” animals swam or climbed higher to escape the waters. But the fossil record disproves this. In every major geologic layer after the appearance of larger animals, small and simple organisms continue to be found alongside larger and more complex ones. Cambrian rocks, for instance, contain both trilobites and large arthropods. Cretaceous rocks contain tiny mollusks alongside dinosaurs. If the flood model were true, we would expect to find all simple organisms trapped in the lowest layers, but instead, complex and simple organisms are consistently mixed throughout Earth’s history. As Prothero observes, the fossil record is best explained by long-term ecological succession and extinction events, not a one-time flood (Prothero 118).

The Physics of Rainfall

Genesis says it rained forty days and nights. But to flood the world that fast, you’d need over 30 feet of rainfall per hour across every square kilometer of Earth’s surface, sustained for more than a month. Earth’s surface area is about 510 million km². At 30 feet (9.14 m) of rain per hour, that amounts to roughly 4.7 billion cubic kilometers of water over 40 days—several times more water than exists on Earth today.

Condensation is the process by which water vapor in the air cools and turns back into liquid droplets, forming clouds and rain. When this happens, the water releases latent heat into the atmosphere. Normally this helps drive weather systems like thunderstorms. But on the global scale required for Noah’s flood, the heat released would have been enough to boil the atmosphere, creating conditions incompatible with life (Hirschboeck 3).

The Air Pressure Problem

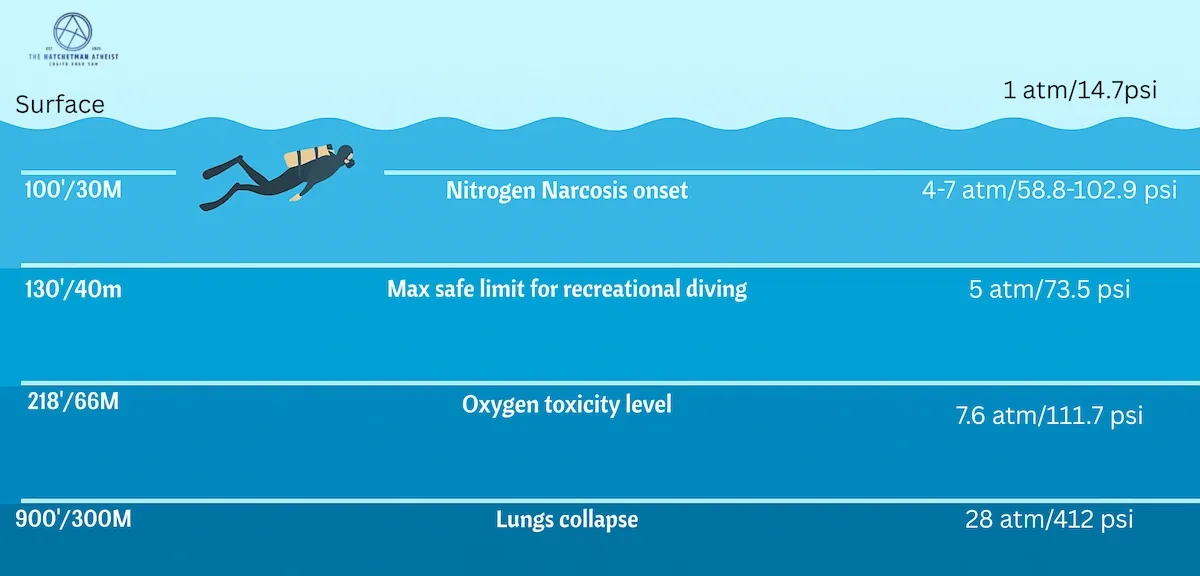

Let’s assume, for argument’s sake, the flood did happen. Raising sea level by nearly 30,000 feet would compress the atmosphere into half its normal space, doubling the pressure. Knox explains that this would be like living at 900 feet underwater (Knox 1255).

At 900 feet below sea level, the human body experiences pressures around 28 times greater than at the surface. Structurally, lungs would collapse, sinuses would implode, and other organs would be crushed by the surrounding pressure. Bones would not necessarily snap immediately, but the soft tissues of the body—lungs, blood vessels, and nervous system—would fail. At this depth, oxygen toxicity becomes a lethal risk: when oxygen is breathed under high pressure, it produces harmful free radicals that damage the nervous system, leading to convulsions, coma, and death. Divers begin to face oxygen toxicity problems at partial pressures of oxygen above 1.6 atmospheres—equivalent to diving only about 218 feet below the ocean’s surface. By comparison, 900 feet of depth produces partial pressures far beyond this lethal threshold.

Nitrogen narcosis is another danger. With nitrogen under extreme pressure, it dissolves into body tissues, impairing brain function. Divers describe the effect as a drunken stupor, which at great depths leads to loss of coordination, hallucinations, and ultimately unconsciousness. The sheer crushing weight of the water pressure would also collapse lungs and damage other organs. Noah and every other land animal could not possibly have survived such an atmosphere, ark or no ark.

Conclusion

The Noah flood fails at every geological, hydrological, and cosmological test. There isn’t enough water to make it happen, no mechanism to drain it afterward, no evidence in the rocks, and no way for humans or animals to survive the physical conditions it would have created. At best, the story reflects ancient people’s memory of devastating local floods—common in Mesopotamia—but not a global event. The rocks tell the truth, and they don’t tell Noah’s story.

Appendix: Biblical Cosmology and the “Windows of Heaven”

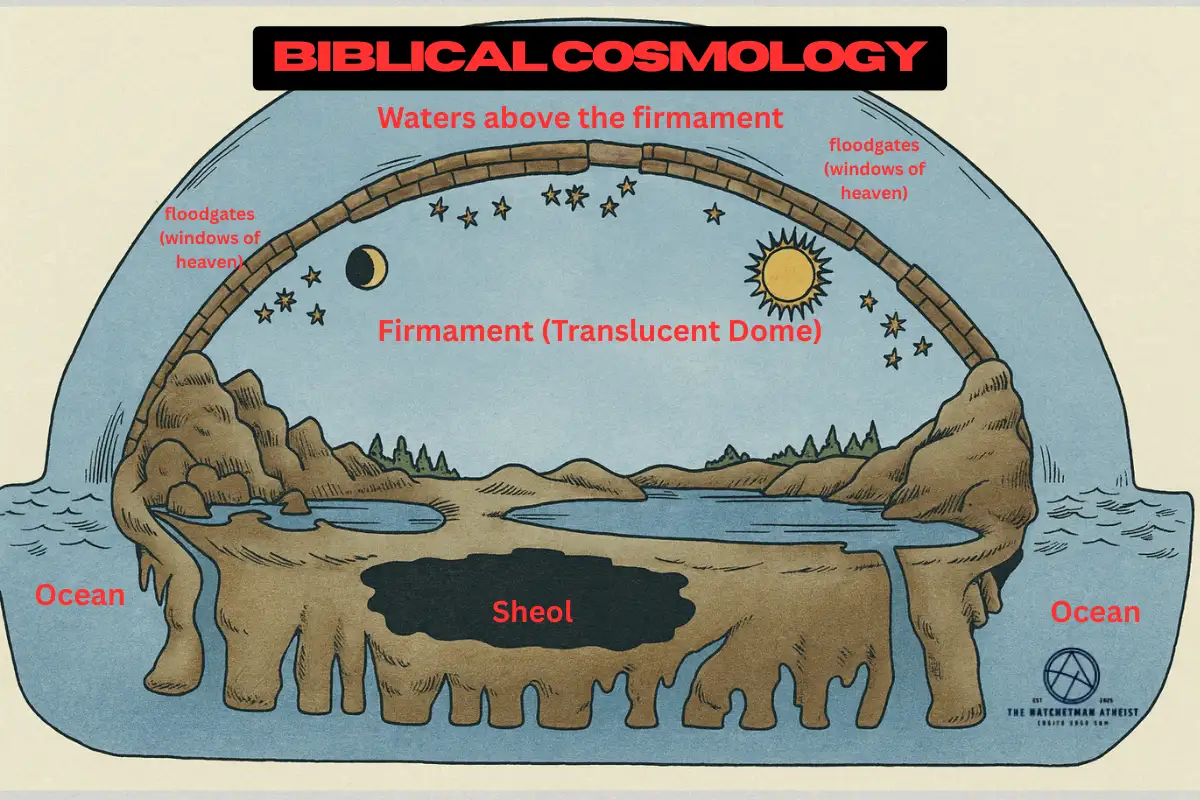

The flood narrative also makes more sense when we recall how the biblical writers thought the universe was structured. Ancient Israelites shared with their Mesopotamian neighbors the idea that Earth was a flat disk covered by a solid dome, the firmament (raqiaʿ). Above that dome were the “waters above,” a vast cosmic ocean. Rain fell when God opened literal windows or sluice-gates in the dome.

Genesis describes creation this way: “And God said, ‘Let there be a dome in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.’ So God made the dome and separated the waters that were under the dome from the waters that were above the dome. And it was so. God called the dome Sky” (Gen. 1:6–8, NRSVue).

Paul Seely, in his study of Genesis cosmology, notes that ancient Israelites understood the firmament as a solid structure that held back the heavenly ocean above it (Seely 229). John H. Walton explains that for the biblical writers, the raqia was not empty space but a barrier holding back waters, with windows or floodgates that could be opened to allow rain to fall (Walton 19). Similarly, Mark S. Smith observes that the motif of waters above the firmament derives directly from older Near Eastern cosmologies (Smith 54).

Thus, when Genesis 7:11 says “the windows of the heavens were opened,” it was not metaphorical poetry but a literal image rooted in this ancient worldview: water from the cosmic ocean pouring through divine floodgates in the sky dome.

Works Cited

Cline, Eric H. From Eden to Exile: Unraveling Mysteries of the Bible. Simon & Schuster, 2012.

Gornitz, Vivien, Cynthia Rosenzweig, and Daniel Hillel. Effects of Anthropogenic Intervention in the Land Hydrologic Cycle on Global Sea Level Rise. Global and Planetary Change, vol. 14, no. 1, 1997, pp. 45–60.

Hirschboeck, Katherine K. Flood Hydroclimatology. University of Arizona, 1988.

Knox, J. C. “Sensitivity of Modern and Holocene Floods to Climate Change.” Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 19, no. 9, 2000, pp. 1253–60.

Montgomery, David R. The Rocks Don’t Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah’s Flood. W. W. Norton & Company, 2012.

Prothero, Donald R. Weird Earth: Debunking Strange Ideas about Our Planet. Columbia University Press, 2020.

Seely, Paul H. “The Firmament and the Water Above. Part I: The Meaning of Raqiaʿ in Gen. 1:6–8.” Westminster Theological Journal, vol. 53, no. 2, 1991, pp. 227–40.

Smith, Mark S. The Priestly Vision of Genesis 1. Fortress Press, 2010.

Walton, John H. The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate. IVP Academic, 2009.