Genesis 1 vs. Science: Why Young-Earth Creationism Fails

Reading Genesis 1 as a modern science textbook isn't just a mistake—it's a category error. Explore why the ancient "Cosmic Temple" model makes sense of chaos monsters and the firmament in ways literalism never can.

Seven Days, Ancient Skies, and the Surprisingly Busy Schedule of an Omnipotent God

If Genesis 1 were a modern account of the universe’s origins, it would be deeply confusing. Light exists before the sun. Days pass before anything exists to measure them. The sky is a solid dome holding back cosmic oceans. Chaos monsters lurk just beneath the surface, occasionally surfacing in Psalms and Isaiah. And somehow, creating grass requires roughly the same narrative effort as creating all the stars.

This is not because the authors of Genesis were careless or unsophisticated. It is because they were not writing science.

To understand Genesis 1, you have to understand the Ancient Near Eastern cultural milieu in which it was written: the assumptions that everyone in the region from Egypt to Mesopotamia to the Levant took for granted. Their shared assumptions about time, space, chaos, and especially divine order predate modern physics by millennia. When read on its own terms, the text is coherent and purposeful.

When read as a literal, modern description of material origins as demanded by young-earth creationism and modern biblical literalism, it collapses almost immediately—usually under the weight of expectations it never agreed to meet.

I. The Category Error at the Heart of Literalism

Why Genesis Is Not Describing Manufacturing Events

Literal readings of Genesis 1 within creation science and young-earth creationist frameworks begin with a quiet but catastrophic assumption: that the text is describing material manufacturing events unfolding across measurable, physical time. Nothing exists, and then God speaks everything into existence. This assumption imports a modern framework—mechanical causation, astronomical timekeeping, and empirical sequencing—into a text that does not operate with those categories. The result is not fidelity to Scripture but a category error.

In modern terms, a “day” is not a metaphysical abstraction. We know a day to be the measure of time that it takes the Earth to rotate one full rotation on its axis. We are able to mark that time with the sun's cyclical appearance and disappearance at 24-hour intervals. But put yourself into a pre-scientific state of mind. It would be easy to imagine that the sun's rising and setting was designed to fit perfectly into a predetermined time period. In other words, the concept of “day” might have existed independent of the Earth and the sun.

This is the day in Genesis 1. It is a divinely appointed time period that existed before there was a sun to rise or an Earth for it to illuminate. The sun was created to rule that time period, to bring order to it with regular and predictable dawns and dusks. Orderly.

The text presupposes a cosmic clock that ticked with days that existed independent of the physical universe. It existed by divine decree, bringing temporal order to creation.

II. Light Before the Sun: Why Genesis Treats Light as a Divine Substance

Genesis places the creation of light on Day One and delays the sun, moon, and stars until Day Four. This is not a literary flourish or a puzzle anticipating modern physics. It reflects an ancient assumption: light was understood as a divine condition, not a physical byproduct of celestial bodies.

In the ancient Near East, light was associated with order, safety, and divine presence. Darkness signaled chaos and threat. Light did not need a mechanical source; the source was the deity. It could be associated with fire, the sun, or the stars, but it was understood as a divinely created attribute placed into those objects by God. Light could exist independently because it was not thought of as an effect at all.

The Hebrew Bible consistently uses light this way:

“The Lord is my light and my salvation; whom shall I fear?” (Ps. 27:1, NRSVUE)

“Light is sown for the righteous, and joy for the upright in heart.” (Ps. 97:11, NRSVUE)

“He reveals deep and hidden things; he knows what is in the darkness, and light dwells with him.” (Dan. 2:22, NRSVUE)

These are not metaphors grounded in physical explanation. They assume light belongs to the divine realm. Genesis follows the same logic. Light exists before the sun because, within this worldview, that sequence is entirely coherent.

John Walton states the point directly: Light in Genesis 1 is not a material object. It is a condition that allows people to function.¹

Mark S. Smith situates this idea within broader West Semitic thought: Light and darkness function as symbols of order and chaos, not as descriptions of physical phenomena.²

Put plainly, the authors of Genesis believed light could exist without physical sources because they believed it came directly from God. Modern science rejects that premise. The conflict is foundational, not cosmetic.

III. Chaos Before Creation

Why Genesis Begins with Disorder, Not Nothing

Genesis 1:2 does not begin with nothing. It begins with unstructured reality:

“Darkness covered the face of the deep.”

The “deep” (tehom) refers to real, physical water, but water understood through an ancient Near Eastern lens. Unbounded water was never neutral. It was unstable, threatening, and hostile to life. Because floods erase boundaries and overwhelm order, water naturally became the primary symbol of disorder. Here, the physical reality and the symbolism are inseparable. The water is chaotic because it is uncontained.

Genesis reflects this shared cultural assumption while carefully reshaping it. The tehom is present, but it is not personified. It has no will, no voice, and no resistance. There is no hint of rivalry. God does not battle the waters; he organizes them. Order emerges not through violence but through speech. Chaos is real, but it is passive.

This restraint matters. In much of the ancient Near East, chaos did not remain an abstract condition. It was frequently given a face.

IV. Leviathan and Company

Chaos Monsters in the Hebrew Bible

In ancient Near Eastern mythology, chaos was often personified as monstrous beings. Disorder was imagined not merely as unruly matter, but as active opposition. Creation, therefore, was framed as conflict: the defeat of chaos powers to secure order and kingship.

This imagery does not disappear in the Hebrew Bible. It survives most clearly in poetry and prophetic rhetoric:

“You divided the sea by your might; you broke the heads of the dragons in the waters. You crushed the heads of Leviathan.” (Ps. 74:13–14, NRSVUE)

“On that day the Lord…will punish Leviathan the fleeing serpent.” (Isa. 27:1, NRSVUE)

These texts draw directly from the shared mythic vocabulary of the region. Figures like Leviathan echo older chaos monsters such as Yam and Lotan from Ugaritic literature. Even when Yam does not appear as a proper name, the sea is repeatedly described as a hostile force subdued by divine power. Yahweh is portrayed using the same imagery once applied to Baal: riding the clouds, mastering the waters, crushing monsters.

This is not casual borrowing. It is deliberate theological repositioning. The biblical authors do not deny the symbolic power of the combat myth; they reassign its roles. Yahweh occupies the cosmic position once claimed by other storm gods, while chaos is stripped of true threat.

As Mark S. Smith observes, the combat myth is not erased but muted.³ Chaos monsters remain, but they are relegated to metaphor and memory. Unlike Genesis 1, where chaos is impersonal and silent, these later texts allow it a voice—only to ensure it is decisively silenced.

V. The Firmament Explained

Biblical Cosmology in Plain Terms

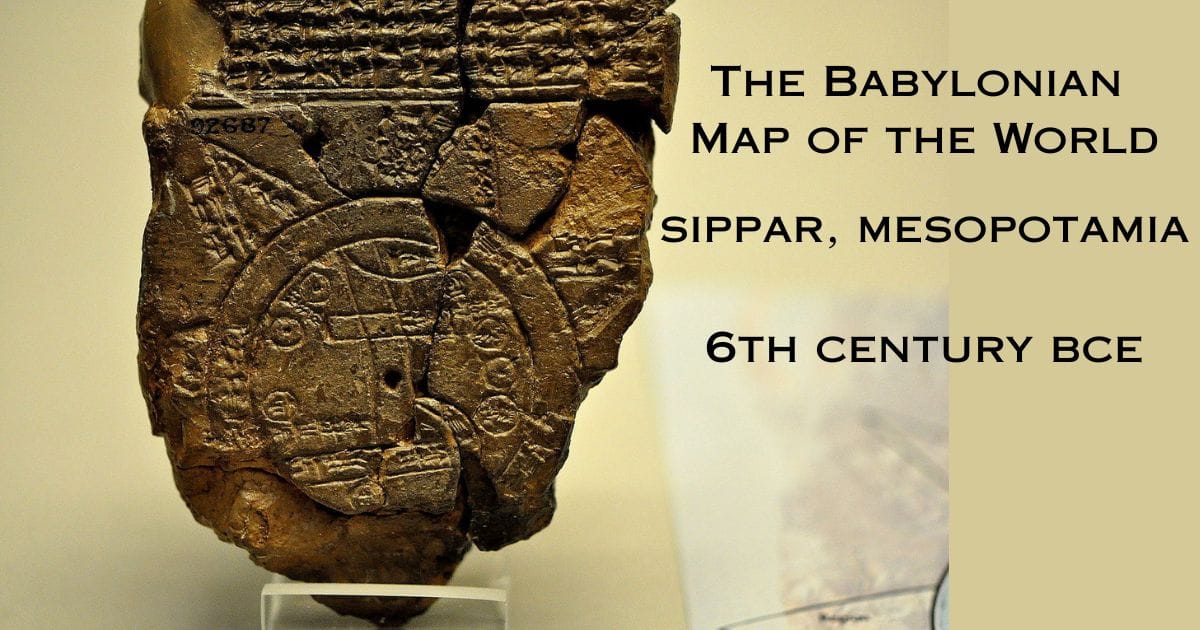

Babylonian Map of the World tablet from Sippar, Mesopotamia. British Museum. Photograph licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0.

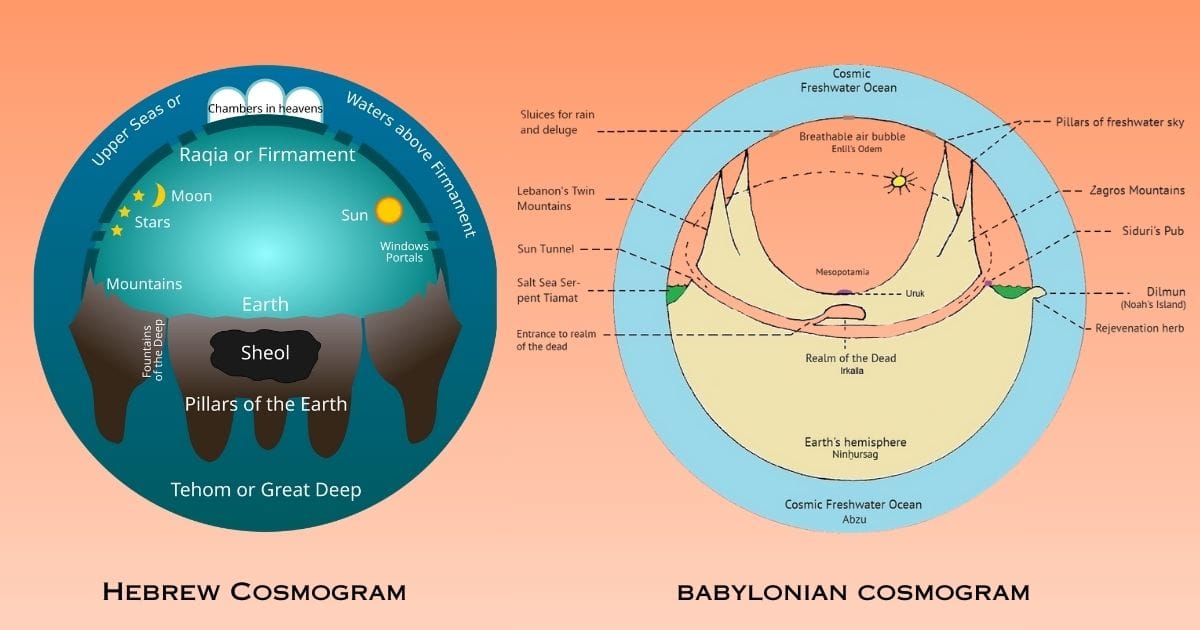

Genesis does not describe empty space awaiting planets. It describes a structured, enclosed world, built by separating waters from waters. The key mechanism for that separation is the raqia.

In the King James Version, Genesis 1:6–8 reads:

“And God said, Let there be a firmament (raqia) in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.”

“And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament.”

The word raqia comes from a verb meaning to beat out or hammer thin, as one would flatten metal. The firmament is not atmosphere, space, or a poetic metaphor. It is a solid structure whose purpose is explicitly mechanical: holding back upper waters.

This cosmology is consistent across the Hebrew Bible:

– Waters below the earth

– A flat land surface

– A solid dome overhead

– Waters stored above the dome

That is why Genesis 7:11 can say:

“The windows of heaven were opened.”

when Noah's flood happened. It was not metaphor. They believed in literal windows in a solid structure that stretched above the Earth.

This model is not uniquely biblical. Nearly identical cosmologies appear in Mesopotamian and Egyptian sources. The sky is a barrier. The heavens are a reservoir. Rain happens when openings are created.

As John H. Walton notes, the raqia is conceived as a solid structure that holds back waters.⁴

This is not a fringe view. It is the consensus of ancient Near Eastern scholarship.

The “Circle of the Earth” Problem

Modern readers often appeal to verses like Proverbs 8:27 to argue that the Bible secretly teaches a spherical earth:

“When he prepared the heavens, I was there: when he set a compass upon the face of the depth.” (KJV)

The word translated “compass” refers to a circle or horizon, not a globe. It describes the visible boundary where sky meets sea, not a three-dimensional planet. The same imagery appears in Isaiah 40:22:

“It is he that sitteth upon the circle of the earth.” (KJV)

A circle is not a sphere. In ancient cosmology, the earth is a flat disk, surrounded by water, capped by a dome. Reading modern physics into this language is not interpretation; it is anachronism.

The firmament meets the earth at the horizon. It is not floating in space. It rests on the edges of the world, enclosing it like a lid.

VI. Creation as Ordering

What Genesis 1 Is Actually Describing

Once the firmament is understood, Genesis 1 becomes much clearer. The chapter is not describing creation from nothing. Darkness, water, and raw material already exist. What God does is organize.

Creation unfolds through:

– Separation (light from darkness, waters from waters)

– Assignment (day, night, seasons)

– Function (lights to govern, humans to rule)

Genesis 1:9–10 continues the same logic:

“Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear.” (KJV)

Nothing is manufactured. Everything is arranged.

Walton summarizes the point succinctly: Creation in Genesis 1 is about the establishment of order, roles, and functions.⁵

Genesis does not deny chaos; it assumes it. What it denies is that chaos has agency. The world is brought into order not by combat, but by categorization and containment. The firmament is the architectural centerpiece of that ordered world—a reminder that Genesis is describing ancient cosmology, not hidden modern science.

VII. Day Four and the Scale Problem

Grass, Trees, and Two Hundred Sextillion Stars

Literalism—particularly young-earth creationism—introduces a problem it rarely confronts: scale.

On day three, God creates all the vegetation on Earth. So, 24 hours for plant life. But on day four—all apparently within the same 24-hour period—God creates the sun, the moon, and the stars. All of the stars. In one day.

Modern astronomy estimates roughly 2 × 10²³ stars.⁶ This exceeds the estimated number of grains of sand on Earth by orders of magnitude.⁷ Genesis treats these acts as narratively equivalent. Plant life = 24 hours. Sextillions of stars, also in 24 hours.

But… how?

If literalists are going to insist on taking this chapter literally, then they have to answer a few questions.

Why is it that God is shown, at times, creating with just his word, but other times it takes him a full day to complete a particular task? Was he physically measuring out the hydrogen for each individual star? Was this a hands-on thing where he physically created it? Or was it all through divine decree?

The issue is not divine ability; it is consistency. If these days are literal 24-hour days as required by six-day creation models, and if God has the superlatives assigned to him by Christian dogma, then why did it take any time at all? If it took him six days to create everything, one can imagine a god who could do it in five and a half days. Wouldn't that make him more omnipotent than the omnipotent deity of Genesis 1? In fact, if the superlatives hold, why wouldn't the entire universe spring instantly into existence as soon as God decided to create it? What precisely was he doing in those 24-hour periods?

The scriptures are silent, but they present a real problem for the concept of an omnipotent god.

The staggering scale of the universe in motion. In a literal 24-hour creation model, the microscopic dot at the beginning of this video is given three times as much narrative focus as the cosmic giants shown at the end.

There are orders of magnitude more stars in the universe than there are grains of sand on earth.

VIII. Ancient Cosmograms Compared

Composite comparison of Babylonian and early Hebrew cosmograms. Sources include Babylonian World Map (Sippar) and “Early Hebrew Conception of the Universe,” both licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike.

IX. Conclusion: Finding Meaning in the Temple

If we let go of the need for Genesis to be a science manual as assumed by creation science and young-earth creationism, we find something much more profound. It is a “Cosmic Temple” inauguration. God is not a cosmic factory worker punching a clock; he is a king moving into his palace, declaring that the world is ordered, functional, and good.

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so on patreon.

References

¹ John Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One.

² Mark S. Smith, The Origins of Biblical Monotheism.

³ Mark S. Smith, The Priestly Vision of Genesis 1.

⁴ John Walton, Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament.

⁵ John Walton, Genesis 1 as Ancient Cosmology.

⁶ Estimate based on data from the European Space Agency.

⁷ Comparison based on calculations by University of Hawaii researchers.

Works Cited

European Space Agency. “How Many Stars Are There in the Universe?” ESA, 2025.

Smith, Mark S. The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts. Oxford University Press, 2001.

---. The Priestly Vision of Genesis 1. Fortress Press, 2010.

University of Hawaii. “The Number of Grains of Sand on Earth.” University of Hawaii News, 2025.

Walton, John H. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Baker Academic, 2006.

---. “Genesis 1 as Ancient Cosmology.” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions, vol. 11, no. 1, 2011.

---. The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate. IVP Academic, 2009.