Ring Species Explained: What Ensatina Salamanders Reveal About Speciation

The Ensatina salamanders of California form a living ring species, where asymmetric mate choice and pheromones reveal reinforcement and speciation in real time.

Ring Species Explained: What Ensatina Salamanders Reveal About Speciation

One of the most common objections to evolution is that “no one has ever seen a species turn into another species.” The claim rests almost entirely on a misunderstanding of what biologists mean by a species and how speciation actually occurs. Evolution does not require sudden transformations or sharp boundaries. It requires populations to become reproductively isolated—by whatever mechanisms—over time.

Ring species matter because they allow us to observe that process while it is still underway.

The Ensatina salamander complex of California is often presented as a tidy classroom illustration of this idea. In reality, it is far messier than the version usually taught. That messiness is not a flaw in the evolutionary explanation. It is the explanation.

Ensatina matters because it shows how new species form not in theory, but in observable, living populations.

Table of Contents

- What Is a Species, Anyway?

- Ring Species 101: Ensatina Around the Central Valley

- Why Ring Species Matter for Evolution

- The Study: Salamander Speed Dating (1986)

- Experimental Design: Who, Where, How

- Results: Reproductive Isolation in Uneven Stages

- Why the Lopsided Love? Reinforcement and Hybrid Costs

- Chemical Conversations and Pheromone Mismatch

- Why This Matters for Evolution

- Conclusion: Speciation Without Sharp Lines

- Related Reading

- Works Cited

What Is a Species, Anyway?

Defining a species is notoriously difficult. There is no single definition that applies cleanly across all forms of life. Botanists, microbiologists, and zoologists often use different criteria because organisms reproduce, hybridize, and diverge in fundamentally different ways.

In zoology, the most commonly used framework is the

Species Concept (Biological Species Concept).

Under this view, a species consists of populations whose members can interbreed with one another and produce fertile offspring, while being

reproductively isolated

from other such populations.

This definition does not require perfect isolation. It requires a trend. Speciation is therefore not a moment but a process: populations gradually accumulate barriers to reproduction—behavioral, chemical, genetic, or ecological—until gene flow is effectively curtailed.

Seen this way, the question is not whether speciation happens, but how far along a population is on that path.

Ring Species 101: Ensatina Around the Central Valley

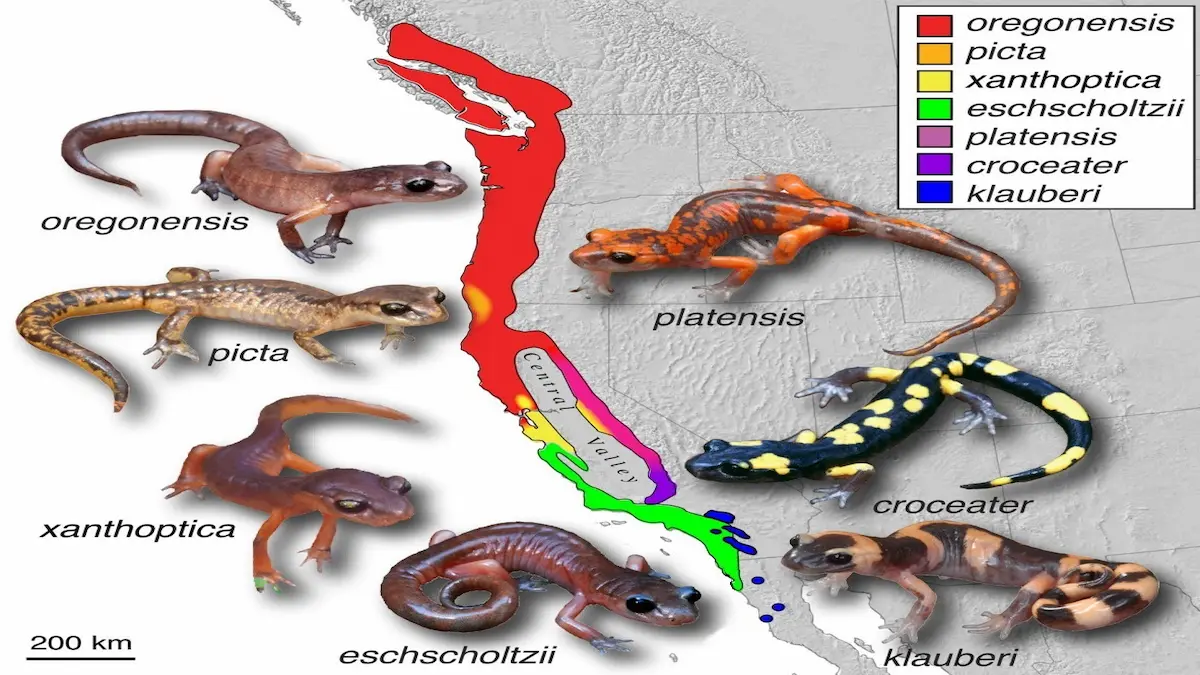

Ensatina eschscholtzii ring species distribution. Image by Thomas J. Devitt, Stuart J. E. Baird, and Craig Moritz, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 2.0. Image resized from the original.

Ensatina salamanders form a chain of populations distributed around California’s Central Valley, a dry agricultural basin that salamanders cannot cross. As the ancestral population spread southward along both the coastal and inland mountain ranges, neighboring populations remained in contact and capable of interbreeding.

At the southern end of this ring, however, the two terminal populations meet again—and largely refuse to mate.

This configuration creates a natural experiment. Along most of the ring, gene flow continues. At the ends, reproductive isolation has begun to emerge. Ensatina therefore occupies an intermediate position: neither a single freely interbreeding population nor a set of fully distinct species.

That is precisely what speciation in progress looks like.

Why Ring Species Matter for Evolution

Ring species have long been cited as evidence that speciation can occur through gradual divergence rather than abrupt separation. Each population differs only slightly from its neighbors, yet cumulative differences can eventually disrupt reproduction.

What Ensatina shows is that reproductive isolation does not appear all at once, nor does it emerge symmetrically. Different barriers arise at different times, and some populations remain compatible long after others have diverged.

The textbook diagram is neat. The biology is not.

The Study: Salamander Speed Dating (1986)

To test whether reproductive isolation had begun to emerge among Ensatina populations, Wake, Yanev, and Brown conducted controlled mate-choice experiments in 1986. Their goal was not merely to ask whether salamanders could mate, but how they behaved when given the opportunity.

That distinction matters. Reproductive isolation often begins as preference rather than impossibility.

Experimental Design: Who, Where, How

Salamanders from adjacent and non-adjacent populations were paired under laboratory conditions. Researchers recorded courtship duration, frequency of mating displays, acceptance or rejection, and the behavior of both sexes.

This approach allowed the researchers to distinguish between full compatibility, partial compatibility, and emerging reproductive barriers—exactly the distinctions relevant to speciation under the biological species concept.

Results: Reproductive Isolation in Uneven Stages

The results showed that reproductive isolation among Ensatina populations is asymmetric rather than absolute. In mating trials involving the two southern terminal forms—Ensatina eschscholtzii along the coastal range and Ensatina klauberi in the inland mountains—successful courtship depended strongly on direction.

In practical terms, the asymmetry reflects female mate choice. In these salamanders, females are the decisive gatekeepers of mating. Courtship may be initiated, but acceptance is not guaranteed. As a result, while females from one population may accept males from another at relatively high rates, females from the second population often refuse males from the first.

In the Wake, Yanev, and Brown experiments, successful courtship in one direction occurred in roughly two-thirds to three-quarters of trials, while the opposite pairing succeeded in only a small minority, often under twenty percent. Courtship behavior in the unsuccessful direction was also shorter and less persistent, indicating early-stage recognition failure rather than mechanical incompatibility.

This asymmetry matters. It shows that reproductive isolation is not an on–off switch. It emerges unevenly, through biased mate recognition and selective rejection, long before complete isolation is reached.

At the southern end of the Ensatina ring, these asymmetries have accumulated into near-complete reproductive isolation. Elsewhere around the ring, compatibility persists to varying degrees.

Why the Lopsided Love? Reinforcement and Hybrid Costs

One mechanism driving this pattern is

reinforcement.

When hybrid offspring have reduced fitness, natural selection favors individuals who avoid mismatched pairings. Over time, this strengthens mate discrimination even between populations that remain genetically similar.

In Ensatina, hybrid zones appear to have imposed such costs, accelerating the evolution of reproductive barriers in some directions but not others. Speciation advances unevenly because selection pressures are uneven.

Chemical Conversations and Pheromone Mismatch

Reproductive isolation in Ensatina is not purely behavioral. Courtship relies heavily on chemical signaling, and pheromones vary across populations.

Males may initiate courtship successfully, only to fail once chemical cues are exchanged. These invisible barriers are easy to miss in simplified accounts, but they are precisely the kinds of mechanisms that drive speciation in animals.

Why This Matters for Evolution

Claims that evolution has never been observed often rely on an unrealistic definition of speciation—one that demands sharp boundaries and completed outcomes. Biology does not work that way.

Ensatina demonstrates that evolution can be observed in the accumulation of reproductive barriers themselves. The process is visible even when the bookkeeping is incomplete.

Under the biological species concept, populations that are partially reproductively isolated are not anomalies. They are exactly what evolutionary theory predicts.

Ensatina is evolution in action not because it fits a diagram, but because it refuses to.

Conclusion: Speciation Without Sharp Lines

The Ensatina salamander complex shows what speciation actually looks like when it is happening: incomplete, asymmetric, contingent, and driven by multiple interacting barriers. Reproductive isolation appears gradually, through preference, chemistry, and ecology, long before any taxonomist redraws the lines.

If evolution required clean boundaries, it would not work. Ensatina shows why it does.

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so on patreon.

Related Reading

- Glossary: Species Concept (Biological Species Concept)

- Glossary: Reproductive Isolation

- The Burden of Proof for Atheists & Believers

- Debunking the Historicity of the Resurrection: A Miracle Too Good to Be True

Works Cited

Coyne, Jerry A., and H. Allen Orr. Speciation. Sinauer Associates, 2004.

Mayr, Ernst. Systematics and the Origin of Species. Columbia University Press, 1942.

Wake, David B., Kenneth P. Yanev, and Richard A. Brown. “Intraspecific Character Displacement in the Ensatina Complex.” Evolution, vol. 40, no. 3, 1986, pp. 512–520.