Endogenous Retroviruses: A Powerful Proof of Evolution

Endogenous retroviruses are ancient viral stowaways in our DNA. Humans and chimps share ERVs in the same genetic locations—an impossibility by chance. These viral fossils are stunning evidence of common ancestry and evolution's undeniable fingerprints.

Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are ancient viral sequences permanently embedded in DNA and passed down through generations. When two species—such as humans and chimpanzees—share the same ERVs in the exact same genomic locations, this is not coincidence. It indicates inheritance from a common ancestor. Scientists have identified at least sixteen such shared ERVs between humans and chimps, and the probability of this pattern arising by random chance is roughly 1 in 10⁹²—far less likely than guessing the correct star in a trillion universes. Some ERVs are shared by humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas, reflecting an older common ancestor. Crucially, there are no ERVs shared exclusively between gorillas and either humans or chimps that are absent in the third species. This nested pattern is exactly what evolutionary ancestry predicts and is incompatible with claims of independent insertion or deliberate design.

ERV's Explained

Quick links:

Table of Contents

- What Are Endogenous Retroviruses?

- Why Location Matters: Genomic Addresses

- ERVs as Genetic Breadcrumbs

- Putting the Odds in Perspective

- The Gorilla Pattern: Nested Inheritance

- The Takeaway

- Works Cited

When scientists compare DNA, they are not looking for vague resemblance or philosophical meaning. They are looking for records—physical traces of events that happened in the past. Some genetic features are especially good at preserving those records. Endogenous retroviruses, or ERVs, are among the best.

ERVs are not abstract ideas. They are literal pieces of viral DNA embedded at precise locations in the genome. And when two species share the same viral sequence in the same genomic location, the explanation is not coincidence. It is inheritance.

This article explains what ERVs are, how they enter the genome, why their specific locations matter, and why repeated independent insertions collapse under probability.

What Are Endogenous Retroviruses?

Retroviruses are a class of viruses with an unusual life cycle. Instead of simply hijacking a cell, they convert their RNA into DNA and insert that DNA into the host’s genome. That means the viral genetic material physically fuses into the DNA of the host cell.

Most of the time, this affects only the infected individual. But on rare occasions, a retrovirus inserts itself into a sperm or egg cell. When that happens, the viral DNA becomes part of the organism’s hereditary material. Every descendant of that individual inherits the viral sequence.

That inherited viral DNA is called an endogenous retrovirus.

Over millions of years, these viral sequences accumulate mutations. Most lose the ability to function as viruses at all. Today, they persist as genetic remnants—molecular fossils—passed down through generations. Roughly eight percent of the human genome consists of such ERV-derived sequences.

What matters most is not what ERVs do now, but where they are.

Why Location Matters: Genomic Addresses

A genome is not a random jumble. It is organized into chromosomes, and each position along those chromosomes has a specific address, called a locus (a fixed physical location on the DNA strand).

When a retrovirus inserts its DNA, it does not aim for a specific address. The genome is enormous—about three billion base pairs long—and while viruses may favor certain general regions, the exact insertion point is largely unpredictable.

The same virus independently inserting into the same locus in two different species is extraordinarily unlikely.

So when scientists find the same ERV at the same locus in humans and chimpanzees, they are not seeing coincidence. They are seeing inheritance from a shared ancestor that already carried that viral insertion.

ERVs as Genetic Breadcrumbs

Researchers have identified at least sixteen ERVs that appear at matching loci in both human and chimpanzee genomes. These are not just similar sequences. They are the same viral remnants embedded in the same chromosomal locations, surrounded by the same neighboring DNA.

Even using conservative assumptions—allowing for preferred insertion regions and some flexibility in exact position—the chance of one retrovirus independently landing in the same locus in two species is about one in five hundred thousand.

That is already small. But this does not happen once.

It happens sixteen times.

When those probabilities are multiplied together, the odds drop to roughly one in ten to the ninety-second power (1 followed by 92 zeros).

Putting the Odds in Perspective

There are an estimated ten to the eightieth power stars in the observable universe (1 followed by 80 zeros).

That number is enormous. But it is still twelve orders of magnitude smaller than ten to the ninety-second power.

You would be more likely to randomly select the exact star someone is thinking of—out of all the stars in the observable universe—in a trillion separate universes than for sixteen identical viral insertions to land in the same genomic locations by chance.

Chimpanzee DNA Similarity: The 98 Percent Claim Explained

Is human and chimpanzee DNA 95 percent similar, or 98.5 percent? The short answer is yes — and the long answer exposes how sound bites flatten real genetics. This article unpacks what those percentages measure, what they omit, and why the confusion persists.

The Gorilla Pattern: Nested Inheritance

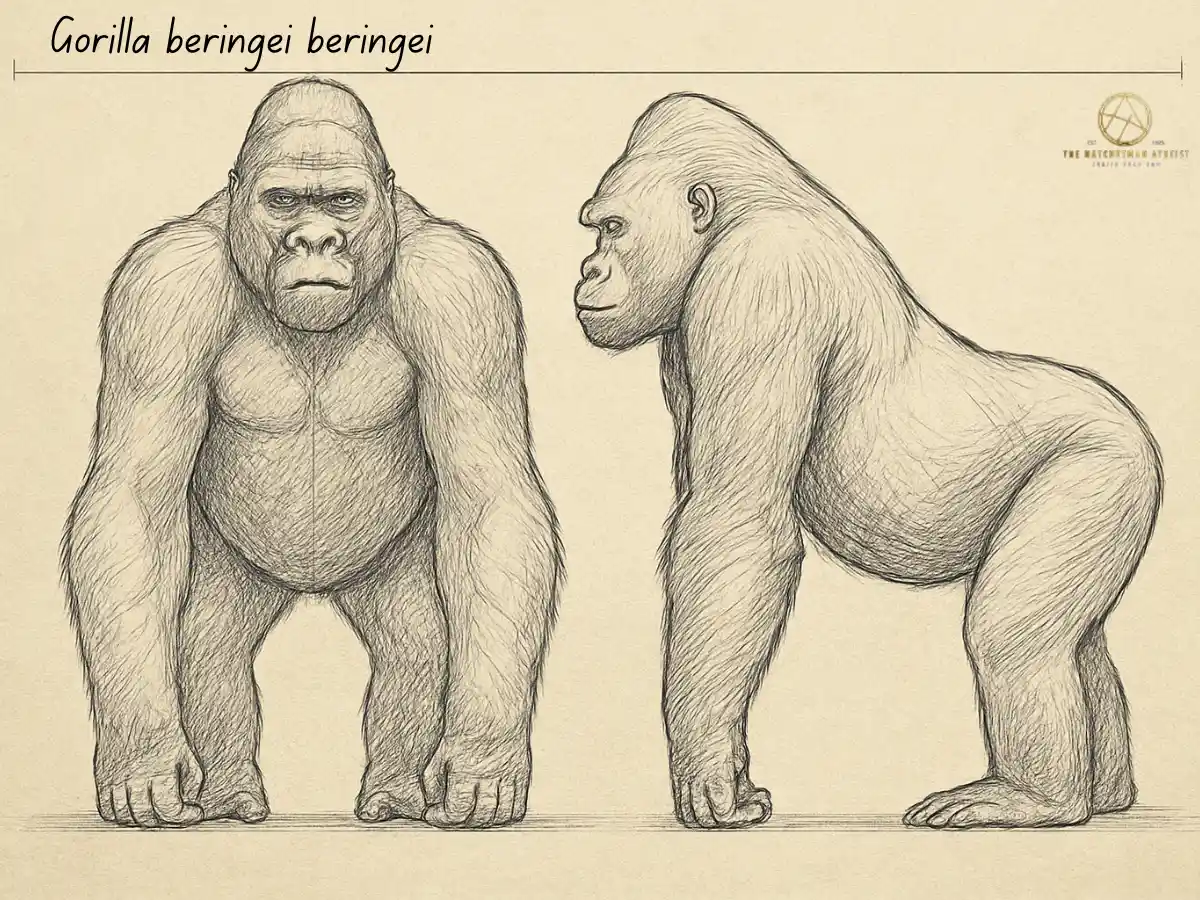

The evidentiary strength of ERVs does not rest only on humans and chimpanzees. Gorillas add an additional, independent layer of confirmation.

Some ERVs are shared by humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas alike. These insertions must have occurred before the common ancestor of all three lineages split.

Other ERVs are shared only between humans and chimpanzees and are absent in gorillas. This pattern indicates viral insertions that occurred after the gorilla lineage branched off, but before humans and chimpanzees diverged from each other.

Crucially, researchers do not find ERVs shared exclusively between gorillas and humans, or between gorillas and chimpanzees, that are absent in the other two. That absence is exactly what shared ancestry predicts and what independent insertion does not.

The ERV distribution forms a nested hierarchy that mirrors the primate family tree derived from anatomy, fossils, and other genetic markers. Independent viral insertions would not generate this orderly pattern. Inheritance does.

The Takeaway

ERVs are physical sequences of viral DNA sitting at precise addresses in the genome.

If humans and chimpanzees did not share ancestry, one must explain why the same viral fragments appear in the same genomic locations in both species again and again, and why those patterns fall into a precise, nested structure when gorillas are included. Independent insertion cannot plausibly account for the evidence.

DNA does not argue. It records.

Testing Creationism Against the Evidence We Actually Observe

This article skips theology and tests claims against measurable reality: genetics, fossils, and geological data. When predictions collide with evidence, only one side adjusts. The other insists reality is wrong.

Works Cited

International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial Sequencing and Analysis of the Human Genome. Nature, vol. 409, no. 6822, 2001, pp. 860–921.

Sverdlov, Eugene D. Retroviruses and Primate Genome Evolution. Landes Bioscience, 2005.

Zhu, Yunlong, et al. Precise Mapping of Retroviral Integration Hotspots by High-Throughput Sequencing. PLoS Pathogens, vol. 9, no. 11, 2013, e1003959.