A DNA Primer for Beginners (FAQ Style)

A simple and clear, step-by-step FAQ on DNA — from double helix structure to mutations and epigenetics — showing how genes shape health, traits, and evolution.

DNA: A Beginner’s FAQ

DNA is the blueprint for life — a molecular instruction manual found in nearly every living cell. It shapes everything from your height and eye color to your body’s ability to fight disease. Understanding how DNA works doesn’t require a degree in genetics; it just takes a clear explanation of the basics. This FAQ walks you through DNA step-by-step, starting with what it is and ending with how it influences traits, health, and even evolution.

1. What is DNA?

DNA, short for deoxyribonucleic acid, is the instruction manual for building and running living things. Almost every cell in your body contains a complete copy of your DNA, packaged tightly into structures called chromosomes. These instructions are written in a chemical code that your cells can read to make proteins — the molecular machines and building materials that keep you alive (Alberts et al. 81–83).

2. What is the genome?

Your genome is the complete set of DNA in your body — all of your chromosomes, plus the small amount of DNA in your mitochondria. It’s the full library of your genetic instructions, containing all the genes and the vast stretches of DNA between them (Lewin 14–16).

3. What is the structure of DNA?

DNA is shaped like a twisted ladder, called a double helix.

The sides of the ladder are made from alternating sugar and phosphate molecules.

The rungs are pairs of chemical bases: adenine (A) always with thymine (T), and cytosine (C) always with guanine (G).

In each chromosome, one DNA strand comes from your mother, and the other strand comes from your father. Together, they form the double-stranded structure (Watson and Crick 737–38).

4. What are chromosomes?

A chromosome is a single, long molecule of DNA coiled up around proteins called histones. Humans have 46 chromosomes — 23 pairs. You inherit one chromosome in each pair from your mother and the other from your father. Chromosomes are like separate volumes in the library of your genetic code (Alberts et al. 104–06).

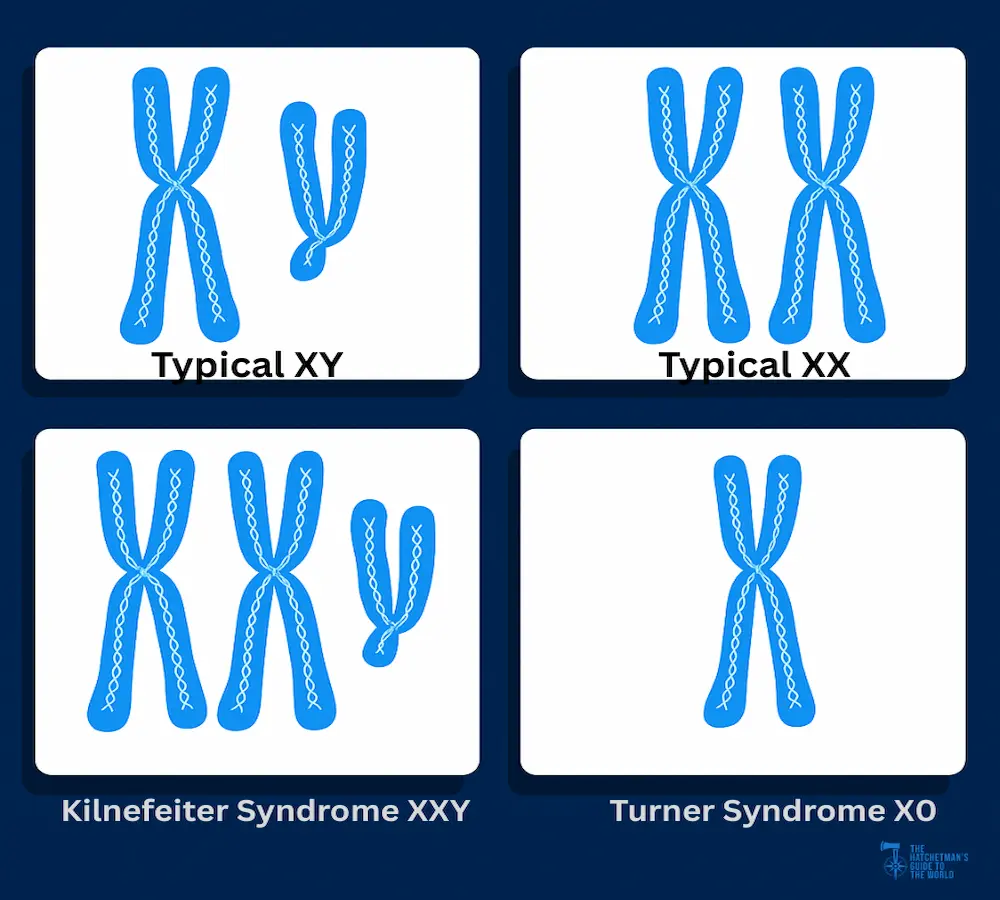

5. What are XX and XY?

Your sex is determined by the 23rd pair of chromosomes:

- XX = typically female

- XY = typically male

The X chromosome is large and carries many genes unrelated to sex, while the Y chromosome is much smaller and contains genes that trigger male development. Males inherit the X chromosome from their mother and the Y chromosome from their father; females inherit one X from each parent (Graves 201–02).

Not all humans have XX or XY chromosome patterns. Variations include XXY (Klinefelter syndrome), X0 (Turner syndrome), XYY, and others. These differences occur in roughly 0.018–0.07% of the population, meaning between 1 in 1,500 and 1 in 5,600 live births. Such variations can influence physical development, fertility, and other traits but do not always cause health problems (Bojesen et al. 445–46).

6. How is DNA passed from parent to child?

Cells that make eggs (ova) or sperm use a process called meiosis. Instead of giving you a full double-stranded chromosome pair, meiosis separates the pairs and shuffles them — a bit like rolling a set of genetic dice. This means each egg or sperm has just one strand of each chromosome, not the full double set. When egg and sperm meet at conception, the two single sets join to form complete chromosome pairs again — one strand from the mother, one from the father (Alberts et al. 151–53).

7. What is a nucleotide?

A nucleotide is the basic building block of DNA. Each one contains:

- A sugar (deoxyribose)

- A phosphate group

- One of the four bases: A, T, C, or G

The sugar and phosphate form the “side rails” of the DNA ladder, while the bases make up the “rungs” (Lewin 28–29).

8. How does DNA store information?

The sequence of the bases — the order of A, T, C, and G — forms a code. This code tells cells which amino acids to join in what order to make a protein. Proteins do most of the work in your body, from building tissues to carrying out chemical reactions (Alberts et al. 188–89).

9. What is the difference between a gene and a codon?

A codon is a sequence of three bases in DNA or RNA that codes for a specific amino acid (or signals a “start” or “stop” in protein building). Think of codons as individual words.

A gene is a complete “recipe” — a stretch of DNA containing the full set of codons needed to make a specific protein (or functional RNA molecule) (Lewin 293–95).

10. How does DNA make proteins? (Step-by-step)

When your body needs a protein:

- Unzipping the DNA: The double helix unwinds at the gene for that protein. The two strands separate like a zipper opening.

- Exposing the template: One strand acts as the template — the set of instructions. The exposed bases are now chemically “sticky.”

- Building the RNA copy: In the watery environment of the cell, free-floating RNA nucleotides drift around. Each RNA nucleotide has a base that bonds with the exposed base on the DNA strand — A pairs with U, C with G, G with C, and T with A.

- Messenger RNA (mRNA) formation: These matched RNA nucleotides link together into a complete chain — an RNA copy of the gene.

- Ribosome reading: The mRNA leaves the nucleus and travels to a ribosome, which reads the code three bases at a time (codons).

- Amino acid assembly: Transfer RNA (tRNA) brings the correct amino acid for each codon, and the ribosome links them together in order.

- Protein completion: The chain folds into its final shape — a functioning protein (Alberts et al. 337–39).

11. What is a locus (plural: loci)?

A locus is a fixed position on a chromosome or DNA strand where a specific gene, genetic marker, or sequence occurs. This can refer to a whole gene, a single base pair, or any identifiable segment. For example, the locus of an endogenous retrovirus (ERV) can be pinpointed exactly, allowing scientists to track where that viral sequence has been inserted into the genome (Lewin 402–03).

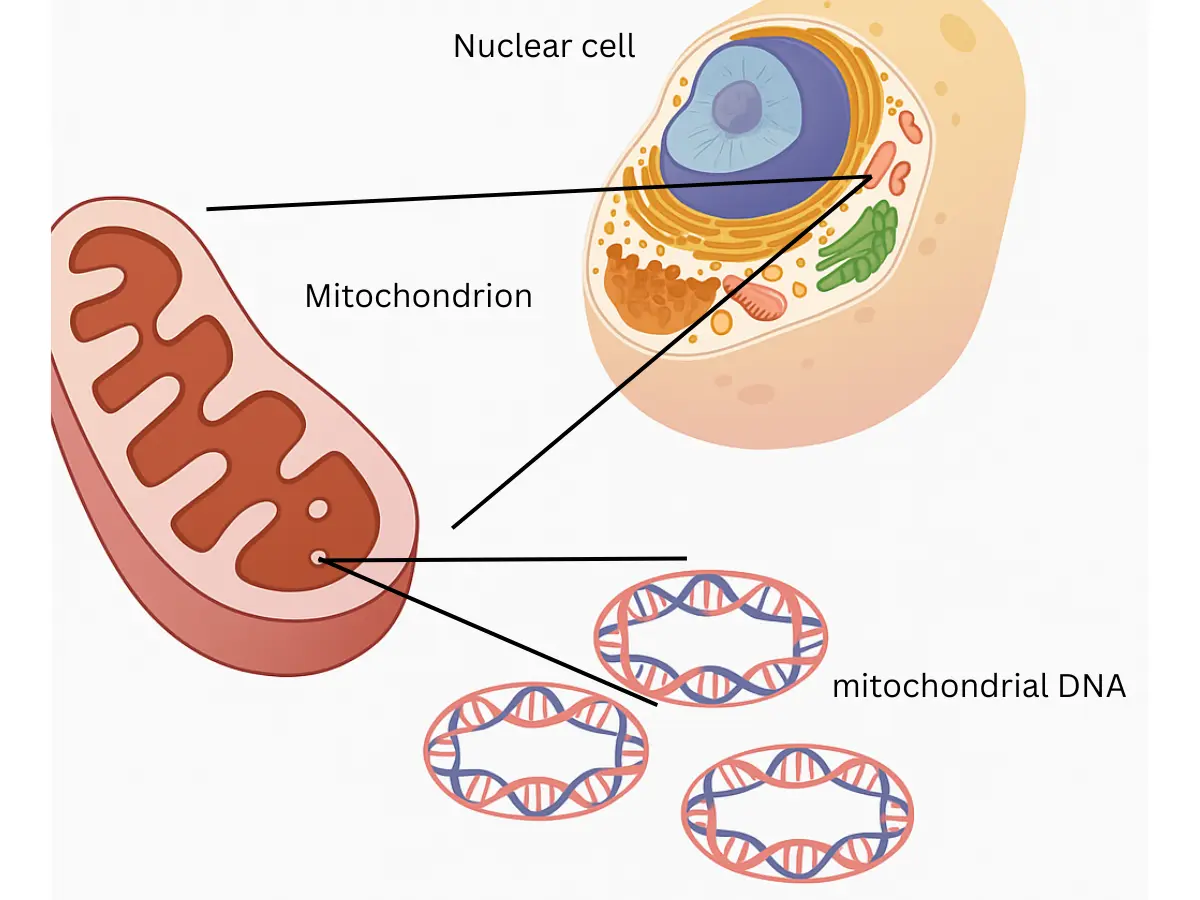

12. What is mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)?

Mitochondrial DNA is a small, circular set of DNA found in mitochondria — the energy factories of cells. It is passed down only from the mother, because the mitochondria in sperm are typically destroyed after fertilization.

One reason mtDNA is so useful to scientists is that it mutates at a fairly steady rate. By counting the number of differences between two samples, researchers can estimate how many generations have passed since they shared a common maternal ancestor (Brown et al. 1219–20).

13. What’s the difference between nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA in inheritance?

Nuclear DNA comes from both parents and is shuffled each generation through meiosis, so it’s a mix of your mother’s and father’s genetic material.

Mitochondrial DNA is passed almost unchanged from your mother, creating a clear maternal line through many generations.

For males, the Y chromosome is similarly passed almost unchanged from father to son, providing a paternal line (Brown et al. 1220–21).

14. What’s the difference between coding DNA, non-coding DNA, and “junk DNA”?

Coding DNA: Instructions for making proteins.

Non-coding DNA: Doesn’t code for proteins but may regulate genes, act as structural elements, or serve other purposes.

Junk DNA: An outdated term for non-coding DNA once thought useless — much of which we now know has roles in regulation and stability (Ponting and Hardison 124–25).

15. What are mutations?

A mutation is a change in the DNA sequence — it can be as small as a single base change or as large as a missing or duplicated section of a chromosome. Mutations occur in every person, many times over a lifetime, often during DNA replication. Some are caused by copying errors, others by radiation, chemicals, or even certain viruses (Cooper and Kehrer-Sawatzki 4–5).

Mutations can and do introduce new genetic information into the genome — for example, a duplication event literally adds extra DNA that wasn’t there before, and a point mutation can create a codon for a new amino acid (Lenski 217–18).

16. Are all DNA differences harmful?

No. Mutations can be harmful, neutral, or beneficial. Beneficial mutations, though rarer, provide raw material for evolutionary change, while neutral ones may persist without effect, and harmful ones can be weeded out by natural selection. Many mutations have no effect at all, and some can lead to useful changes. The variation created by mutations is an important driver of adaptation over generations (Futuyma and Kirkpatrick 157–59).

17. What is epigenetics?

Epigenetics is the study of chemical changes to DNA or its associated proteins that affect how genes are turned on or off without altering the DNA sequence itself. These changes can be influenced by environment, diet, stress, or toxins, and in some cases, can be passed to future generations. Epigenetic markers act like annotations in your genetic “book,” telling cells which chapters to read and which to skip (Jablonka and Lamb 237–38).

Conclusion

From the twisting ladder of the double helix to the way genes turn into proteins, DNA is at the heart of all life. It’s both remarkably stable — preserving instructions over generations — and endlessly adaptable, allowing life to change and evolve. Whether you’re exploring ancestry, learning about health, or simply curious about what makes us who we are, understanding DNA gives you a powerful window into the living world. For a deeper dive into how DNA can record the history of ancient infections, check out my post on endogenous retroviruses (ERV).

Key Takeaways

- DNA is the universal instruction manual for all living things.

- Your genome includes both nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA, inherited in different ways.

- Genes are recipes for proteins, while codons are the three-letter “words” in the genetic code.

- Mutations can be harmful, neutral, or beneficial — and they can add new information to the genome.

- Epigenetics controls which genes are switched on or off without changing the DNA sequence.

- Understanding DNA helps explain inheritance, health, evolution, and even ancient biological history.

Works Cited

Alberts, Bruce, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 7th ed., Garland Science, 2022.

Bojesen, Anders, et al. "Klinefelter Syndrome." Nature Reviews Disease Primers, vol. 1, 2016, pp. 445–454.

Brown, William M., et al. "Mitochondrial DNA Sequence of Primates: Tempo and Mode of Evolution." Journal of Molecular Evolution, vol. 18, 1982, pp. 1219–1223.

Cooper, David N., and Hildegard Kehrer-Sawatzki. Human Gene Mutation. 2nd ed., Garland Science, 2008.

Futuyma, Douglas J., and Mark Kirkpatrick. Evolution. 5th ed., Sinauer Associates, 2023.

Graves, Jennifer A. Marshall. "Human Y Chromosome, Sex Determination, and Spermatogenesis—A Feminist View." Reproduction, vol. 121, no. 2, 2001, pp. 201–210.

Jablonka, Eva, and Marion J. Lamb. Evolution in Four Dimensions. MIT Press, 2014.

Lenski, Richard E. "Experimental Evolution and the Dynamics of Adaptation and Genome Evolution in Microbial Populations." ISME Journal, vol. 11, 2017, pp. 218–224.

Lewin, Benjamin. Genes XII. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2017.

Ponting, Chris P., and Ross C. Hardison. "What Fraction of the Human Genome Is Functional?" Genome Research, vol. 21, no. 11, 2011, pp. 124–135.

Watson, J. D., and F. H. C. Crick. "Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids." Nature, vol. 171, no. 4356, 1953, pp. 737–738.