Daniel: The Post-dated Prophet

Prophecy is easy when you’re writing after the fact. Daniel’s timeline doesn’t lie—but its author might.

Daniel’s Setting vs. Daniel’s Reality

The Book of Daniel is a fascinating case of apocalyptic fan fiction posing as prophetic insight. Conservative interpreters insist it was written during the 6th century BCE Babylonian exile, but serious scholars aren’t buying it. The real story? A text from the 2nd century BCE trying to pass as an ancient oracle.

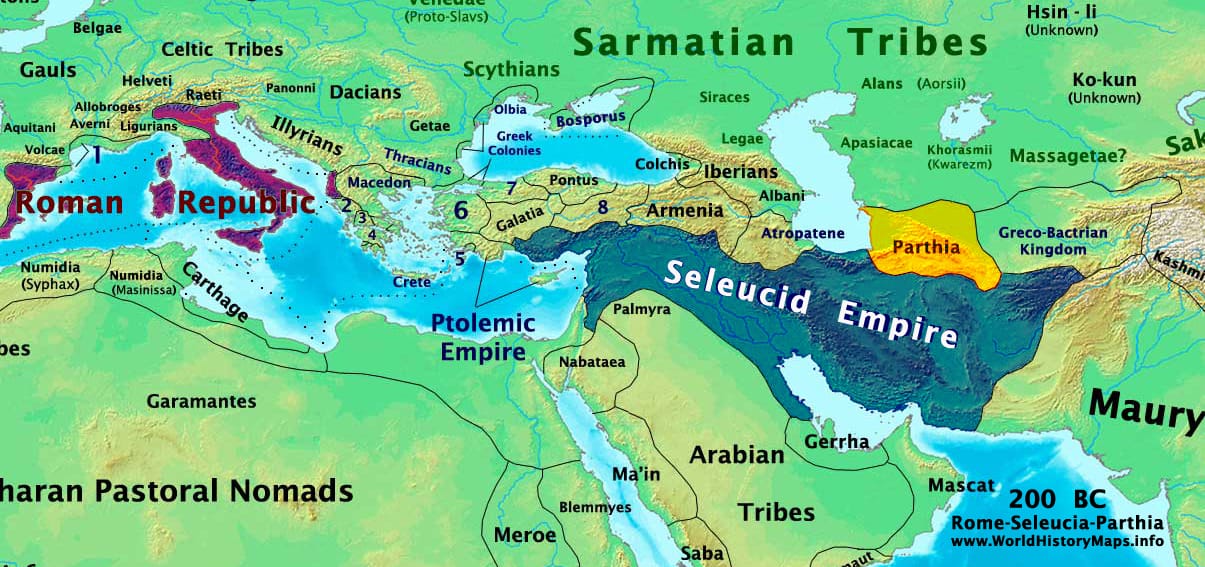

Here’s the setup: Around 597 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar II and the Babylonians were crushing rivals and scooping up territories. The Hebrew kingdom of Judah tried playing both sides with Egypt and Babylon, but that didn’t end well. After repeated rebellions, Babylon had enough, sacked Jerusalem, and destroyed the Temple—yes, the first one—and deported Judah’s elites to Babylon (2 Kings 24:10-17). That’s the exile Daniel pretends to be set in—complete with a Jewish seer charming pagan kings. But the book’s details scream Seleucid, not Neo-Babylonian. Actual Babylonian court protocol was steeped in Chaldean astrology, complex bureaucratic ranks, and Akkadian—not the mishmash of Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, and Persian that we see in Daniel. And let’s not ignore the giveaway in Daniel 3:5, listing musical instruments like lyres, zithers, and trigon—Greek imports that wouldn’t be out of place in a Hellenistic-Greek jam session, but definitely didn’t exist in 6th-century Babylon.

Chapter 11: The History Cheat Sheet

Chapter 11 is the crown jewel of postdiction—vaticinium ex eventu, if you want to impress your Latin teacher—prophecy written after the fact. It’s so historically accurate it reads like a cheat sheet: it follows the breakup of Alexander the Great’s empire, including a nod to the strikingly specific prophecy of a powerful king whose empire would be divided after his early death (Daniel 11:3-4). The feud between the Seleucids (in Syria) and the Ptolemies (in Egypt), and the drama that ensued. Starting in Daniel 11:2, we get Persia’s final kings, then Alexander, then his successors. From verses 5 to 20, Daniel maps out the power struggle between these Hellenistic dynasties with uncanny precision. The King of the South is Ptolemy I. The King of the North is Seleucus I. We see marriages (like Berenice and Antiochus II), betrayals, invasions, and even tax policies (thanks, Seleucus IV). It’s all there—until we hit Daniel 11:40, where Antiochus IV goes rogue in the text.

Prophetic Glitch: Antiochus Goes Off-Script

Up to Daniel 11:39, things are rock solid. Then suddenly, Antiochus is depicted launching an imaginary campaign against Egypt, getting divine judgment, and dying in a way that doesn’t match history. Reality check: Antiochus IV died in Persia, probably of illness, not in a dramatic battlefield clash as Daniel 11:45 suggests. For those keeping track, the scene places his demise "between the sea and the beautiful holy mountain"—a poetic flourish, sure, but geographically incoherent. As Collins notes, "The account remains accurate until about 167 BCE, after which it becomes increasingly detached from actual events" (Collins, Daniel, p. 37).

Interested in biblical prophecy fails? Check out this one on the mark of the beast

Linguistic Red Flags

Historians figured this out through textual analysis and linguistic clues. The Hebrew-Aramaic split is one thing—chapters 1 and 8–12 are in Hebrew, while chapters 2–7 are in Aramaic—but the smattering of Greek vocabulary is damning. Why is Aramaic important? Because while it was widely used across the Near East as a lingua franca during the Persian and early Hellenistic periods, its prominence in Daniel’s middle chapters suggests a much later origin than the Babylonian period. Greek terms in a supposedly 6th-century Babylonian text? Try harder. As Grabbe points out, "The references to Hellenistic (Greek) customs and events reflect a world far removed from the Babylonian exile" (Grabbe, p. 452).

Hellenism Hits Hard

This brings us to Hellenism. After Alexander the Great blitzed through the Near East (c. 334–323 BCE), he left behind a fractured empire soaked in Greek culture. Hellenism meant speaking Greek, building gymnasiums, worshipping Greek gods, and thinking Socratically. For many Jews—especially elites—it was tempting to blend in. But that cultural drift clashed hard with traditional Judaism.

The Maccabean Revolt

Enter Antiochus IV Epiphanes, Seleucid king from 175–164 BCE. Not content with passive assimilation, he actively tried to erase Jewish practice. He outlawed circumcision, Sabbath observance, and Torah study. He didn’t stop at defiling the Temple with a statue of Zeus—he sacrificed a pig on the altar. That’s not just sacrilege; it’s cultural warfare (1 Maccabees 1:41-50).

The Jewish response? The Maccabean Revolt. In 167 BCE, led by Judas Maccabeus, a band of religious zealots turned freedom fighters kicked off a campaign that eventually reclaimed the Temple and sparked Jewish independence under the Hasmoneans. It was messy, brutal, and shockingly successful.

Daniel’s Real Agenda

Daniel, likely written around 165 BCE, was composed in this climate. It wasn’t just scripture—it was resistance literature. By accurately describing past events as prophecy, the book built credibility with readers. If Daniel got all that right, surely his predictions of Antiochus’s downfall and divine vindication were next. Spoiler: they weren’t. But by then, the damage was done—in a good way. The people believed.

As scholar Carol Newsom puts it, "The function of the text was not prediction but persuasion—it sought to interpret recent history in the light of divine providence" (Newsom, Daniel, p. 321).

So no, Daniel wasn’t a Babylonian wunderkind decoding dreams in 600 BCE. He—or rather, the anonymous writer—was a savvy Judean in the 160s BCE, spinning history into theology with just enough accuracy to inspire faith.

Check out this post on human sacrifice in ancient Israel

Works Cited

Collins, John J. Daniel: A Commentary on the Book of Daniel. Fortress Press, 1993.

Grabbe, Lester L. A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period, Volume 2. T&T Clark, 2008.

Newsom, Carol A. Daniel: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press, 2014.

New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition (NRSVue).

1 Maccabees. The New Oxford Annotated Bible, NRSVue, Oxford University Press, 2021.

2 Kings. The New Oxford Annotated Bible, NRSVue, Oxford University Press, 2021.