Before the Bible, Part 1 -Excavating the Bible: How a Pharaoh’s Inscription Changed Everything

A pharaoh’s boast carved into stone three thousand years ago rewrote biblical history. The Merneptah Stele (1208 BCE) names “Israel” for the first time—not as a kingdom but as a people. Archaeology, not scripture, now tells the story of Israel’s birth from Canaan’s collapse.

Introduction – Excavating the Bible

Picture this: a pharaoh’s boast carved into black granite three thousand years ago—the first time Israel appears in human history.

Not in the Bible. Not in prophecy. In stone.

Most of us were handed the Bible as a finished story—complete, polished, already bound in leather.

Creation flows neatly into covenant, patriarchs become kings, and history marches forward as if the script had always been there.

But the truth is stranger.

The Bible wasn’t born whole; it’s a layered monument of edits, rewrites, and political spin—centuries of people trying to explain their world and justify their place in it.

These early writers lived in a time when civilization itself was still experimental. Gods came and went with dynasties; sacred stories shifted with every regime. What one tribe swore was eternal truth, another reshaped to fit its own reality.

And when power finally concentrated under Israel’s kings, religion became statecraft. Kings and priests discovered that whoever controlled the national origin story—who the people were, and who their god was—controlled everything else.

The Bible isn’t a photograph of the past. It’s an archaeological tell, a mound built up layer by layer.

To understand ancient Israel, we have to dig through those layers.

We must read the Bible not as revelation but as archaeology—a long excavation through centuries of edits and reinterpretations, revealing how a people, their gods, and their ideas evolved over time.

The Merneptah Stele: Israel’s First Appearance in History

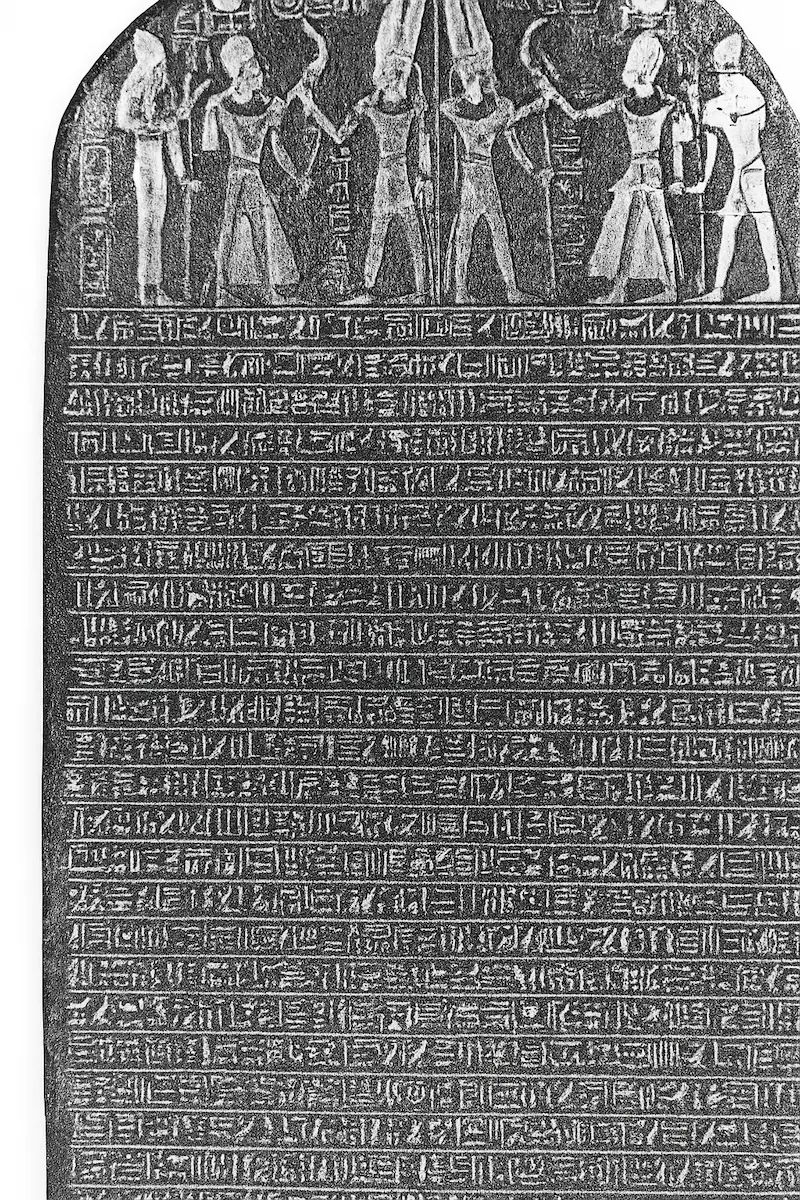

In 1896, British archaeologist Flinders Petrie uncovered a black-granite monument while excavating the mortuary temple of Pharaoh Merneptah at Thebes—a royal victory stele dated around 1208 BCE.¹

Most of the inscription is routine propaganda celebrating the pharaoh’s victories over Libyan and Canaanite foes. But the final stanza lists four rebellious peoples in Canaan:

*“Ashkelon is carried off; Gezer is captured; Yanoam is made as non-existent; Israel is laid waste, his seed is no more.”*²

The Merneptah Stele in full. Discovered at Thebes in 1896 by Flinders Petrie, it records Merneptah’s victories in Canaan. Line 27 contains the earliest historical reference to Israel.

That single line detonated biblical chronology. The hieroglyphic determinative after Israel identifies a people, not a city or kingdom.³ Unlike Ashkelon, Gezer, or Yanoam, Israel had no walled towns, no palace, no bureaucracy—just scattered highland villages. The archaeology backs it up: simple four-room houses, grain silos, goat pens, and pottery styles inherited directly from Late Bronze Age Canaan.⁴

Merneptah’s campaign likely followed his victory over a Libyan coalition, when Egyptian forces pushed north to reassert control in Canaan.⁵ Other Egyptian records confirm similar raids across the 13th century BCE.

The implications are brutal for the traditional timeline.

If Israel already existed in Canaan by 1208 BCE, it could not also be marching out of Egypt or storming Jericho under Joshua.

The Exodus and Conquest stories fall apart as literal history.⁶ Whatever Israel was, it was indigenous—local Canaanites who re-imagined themselves as something new.

One carved sentence, buried for three millennia, rewrote the story. From that moment on, history and scripture no longer matched—and archaeology, not theology, became the referee.

The Problem with the Traditional Story

For centuries the biblical sequence went unchallenged: slaves flee Egypt, wander Sinai, conquer Canaan by divine command. It’s tidy, heroic—and false.

Archaeology tells a different story:

- No trace of a mass Exodus anywhere in Egypt or Sinai.

- No destruction horizon across Canaanite cities that fits Joshua’s campaign.

- Every artifact points to local continuity, not foreign invaders.

What we actually find are hundreds of new agrarian villages in the central highlands—founded just after Egypt’s empire collapsed. Their material culture is Canaanite through and through. The story in the dirt is not one of invasion, but of reorganization and survival.

This is the real beginning of Israel: not a miracle, but a social evolution born from collapse.

A New Way to Read the Bible

Modern scholars stopped asking “Did it happen?” and started asking “Why tell it this way?”

That’s where the real excavation begins—inside the text.

Each biblical book mirrors the politics of its own moment: the rise of kings, civil war, exile, reconstruction. Every edit and addition is a clue to how later writers re-imagined their ancestors and their god to make sense of their own age.

Read this way, the Bible becomes a record of cultural memory, not divine dictation—a chronicle of people reinventing themselves through story.

Looking Ahead

In the next chapters we’ll trace that transformation:

how scholars map Israel’s origins, where Yahweh came from, why the Exodus may have begun as one family’s tale, and how a southern storm-god became the creator of heaven and earth.

Next: The Four Competing Birth Stories — the rival theories that challenge everything we thought we knew about Israel’s beginnings.

If you find this work valuable and want to support future research and writing, including research and web-hosting costs, you can do so on patreon.

Works Cited

¹ Petrie, W. M. Flinders. Six Temples at Thebes, 1896. Egypt Exploration Fund, 1897.

² Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Ed. James B. Pritchard, Princeton UP, 1969.

³ Hasel, Michael G. “Israel in the Merneptah Stela.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 296 (1998): 45–61.

⁴ Finkelstein, Israel, and Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Free Press, 2001.

⁵ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton UP, 1992.

⁶ Dever, William G. Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? Eerdmans, 2003.